Error: No videos found.

Make sure this is a valid channel ID and that the channel has videos available on youtube.com.

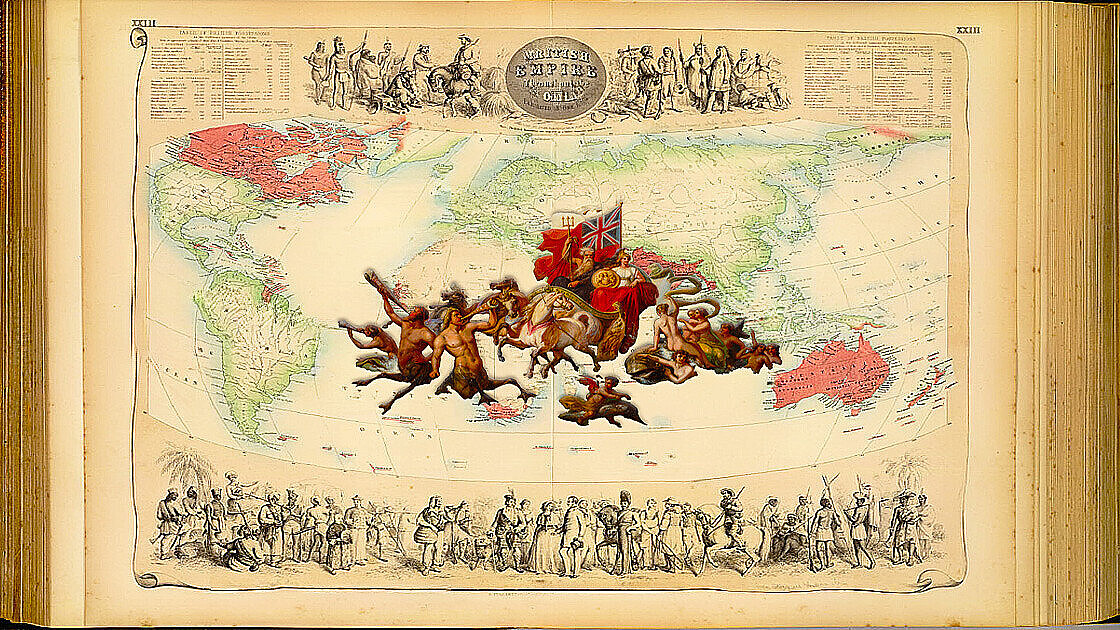

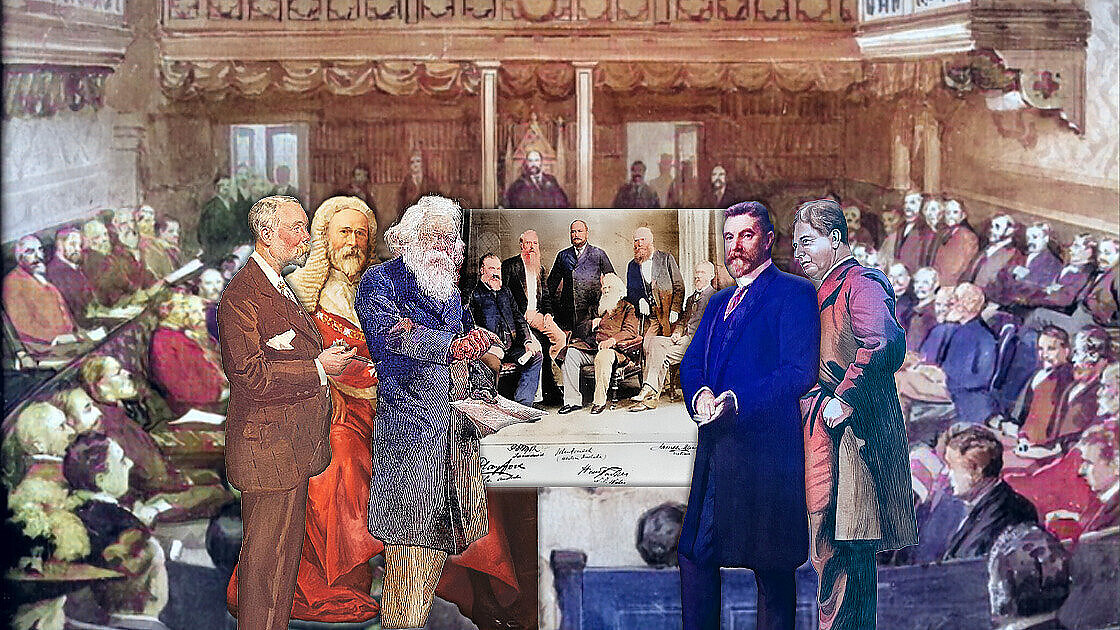

Australian Constitutional Convention of 1998.

In early 1998, the Old Parliament House in Canberra, Australia, became the centre of a significant event known as the Constitutional Convention. The purpose of this event was to address a critical matter that would impact Australia’s future, namely whether the country should become a republic or maintain its current system. Esteemed personalities from various backgrounds gathered to engage in constructive and thought-provoking discourse. However, as the summer of 1998 approached, Robert Manne, an Associate Professor in Politics at Monash University and a regular columnist, expressed surprise in the Sydney Morning Herald (1 February 1999) about what he described as “infighting” within Australia’s Republican Movement (ARM). Even if the Republican camp were united, he noted, persuading a majority of Australians and a majority of states during the upcoming referendum would have been immensely challenging. However, with an “internally divided, self-lacerating Republican Movement,” these challenges would be insurmountable. Manne concluded by saying that “this fatal contradiction at the heart of Australian republicanism had emerged in a way no Australian monarchist at the Constitutional Convention could have predicted.”

It’s not uncommon for Republicans to have disagreements amongst themselves. History has shown similar conflicts between different political groups, such as Cromwell’s Roundheads and the Levellers, the French Girondins and Jacobins, the Russian Mensheviks and Bolsheviks, and the Stalinists and Trotskyists. The 1998 Constitutional Convention also saw clear and unsurprising divisions. Despite this, Manne seemed surprised by the outcome.

It is important to note that the terms “republic” and “republicanism” have multiple interpretations, rendering them impractical for use in discussions pertaining to Australia’s political system. Despite this, there is a persistent call for a plebiscite on the matter of Australia becoming a republic, as well as a continuous discourse in politics and media regarding “the” republic. However, the notion being presented by the Australian Republican Movement (ARM) is tightly regulated, with no place for the monarchy. In other words, their objective is to remove the monarchy at all costs. This has become increasingly evident in recent times.

Authentic Republicans hold a deep-seated belief in the importance of fostering people’s engagement and involvement in the workings of government, in contrast to the ARM’s objectives, which include limiting such participation. Additionally, they place great emphasis on the implementation of checks and balances as a mechanism for ensuring that power is regulated effectively. It is worth noting that there are several similarities between true Republicans and constitutional monarchists, as constitutional monarchies often exhibit a high degree of democratic governance. This underscores the shared focus on ensuring that power is distributed in a manner that is responsive to the needs and desires of the people.

Real Republicans, unlike the ARM, do not focus solely on the crown. Ted Mack, a prominent real Republican from New South Wales, is an example of this. During his time as Mayor of North Sydney, he successfully implemented Citizen Initiated Referenda. He has also opposed the generous superannuation funds for MPs and has resigned from parliament twice just before becoming eligible for a pension. Mack’s true Republican beliefs extend beyond these issues and include promoting popular involvement in government, including direct elections.

In the midst of the 1998 Constitutional Convention elections, Australia’s Republican Movement (ARM) presented a proposal that aimed to establish a direct presidential election process by the people. This suggestion proved to be quite popular and managed to secure the ARM more votes. Furthermore, it also allowed the Republican factions to unite and work together towards a common goal. Although the proposal held great promise in terms of its potential benefits, it ultimately failed to come to fruition.

What were the origins of the Constitutional Convention? It all began in 1995 when Paul Keating, the then-prime minister, took a closer look at the 1993 report of the Republic Advisory Committee, which was chaired by Malcolm Turnbull. After thoroughly reviewing the report, the government announced its policy on June 7th, 1995, stating that Australia should become a republic by 2001. The very next day, John Howard, who was then the leader of the opposition, proposed a People’s Convention. This suggestion had also been put forward by his predecessor, Alexander Downer. Interestingly, while constitutional conventions played a crucial role in the federation of Australia, none had been held in the 20th century.

Until 1998, proposals for constitutional change came from governments, sometimes advised by specialist bodies. The Republic Advisory Committee, consisting only of Republicans and bound by its terms of reference to come up with a Republican model, was the most partisan of these. Although often criticised for “manipulating” the process, the revival of the convention as an instrument for constitutional review was a democratic approach. And it was much more generous and fair to Republicans than the former prime minister had been to monarchists and other constitutionalists.

The convention was made up equally of elected and nominated delegates. Some commentators suggested that because of the nominated delegates, the convention was stacked by the Howard government. This is untrue. A substantial number of places were reserved for nominees of the state and federal parlia¬ments, which ensured a wide range of representation and views. Many, if not the majority, turned out to be Republicans.

It was made clear that if a republican model were adopted by the convention, it would be put to the people. Alternatively, there would be an indicative plebiscite offering choices.

The campaign that preceded the election of delegates demonstrated that there is no level playing field between the principal groups, the ARM and the ACM. The ACM estimates that the ARM outspent it in advertising by a factor of ten –about $ 5 or $6 million against $500,000. The ARM was able to broadcast a large number of television advertisements. The ACM had none. In the voluntary postal ballot, the ARM had the resources and the manpower of the ALP and ACTU behind it, evidenced by the high voting returns in safe Labor electorates. Many ALP MPs used their offices to mail out encouragement to voters. This was replicated by a few coalition MPs in favour of the ACM, but only in South Australia. And even then, the coalition MPs were divided, only some supporting the ACM. But the ACM led the vote in South Australia!

Apart from some small newspaper advertising, the ACM advertised on the radio. Its campaign material was circulated by its own supporters — not by a compliant political party. Of the other groups, only Clem Jones’ Queensland Republic Team advertised extensively. ACM was warned that it could lag up to 20 per cent behind the ARM. Such would be the effect of the ARM’s advertising, the support it had enjoyed over the years of the Keating government, and its strong media backing.

In fact, the ACM and its allies gained 30.67 per cent of the vote. The ARM obtained 30.34 per cent. Many of those who voted for ARM must have done so believing its claims that it would seriously countenance direct election. But soon after the convention opened, the ARM moved to close off any further discussion of direct election. This was too much for the independent Republicans, who threatened a walkout. The ARM had to retreat and allow further discussion.

WHAT DID THE CONVENTION ACHIEVE?

This was the subject of a law forum in the 1998 issue of the University of New South Wales Law Journal, Vol 4, No. 2 (UNSW). All the following comments come from that journal unless otherwise indicated. Cheryl Saunders, a prominent academic lawyer, said: “While some elected delegates had formerly been politicians, the convention generally broadened the range of people normally involved in the development of proposals for constitutional change.”

Moira Rayner, a Republican delegate, said: “It ran efficiently. It did not collapse, as it could have, on the second day. It got a result.” Her final conclusion was, “We missed a chance in February.” Sir Harry Gibbs disagreed: “No doubt a constitutional con¬vention should include representatives of all schools of political and constitutional thought, but the representation of sectional interests is more likely to divert attention from the constitutional issues than to assist in resolving them.” John Uhr, Director of Public Policy at Australian National University, maintained that the process was good even if the outcome wasn’t:

The Convention was an important illustration of Australian democracy at work. An assessment of the worth of how the Convention went about its work can tell us much about the strengths and weaknesses of democracy in Australia … As a process, the Convention proved valuable as an example of what can be achieved through wider community consultation over the agenda of government and closer public participation in government decision making. I remain sceptical about the enduring qualities of the final recommendation.

Yet Attorney-General Darryl Williams took a quite different view, which George Winterton explained is justifiable in terms of the government’s purpose: “[Williams] recently declared the February 1998 Constitutional Convention ‘an outstanding success’. This is a fair assessment if the convention is judged against its designated purpose — to decide whether Australia should become a republic, when this should occur, and which republican model would be put to referendum. However, at least for repub¬licans, the convention will ultimately have failed unless a satisfac¬tory model of republican government is approved at the referendum.”

The convention soon demonstrated the vacuity of the terms republic and republicanism, at least as they are being used now in Australia.

Professor Greg Craven writes that whereas previously, antipodean republicanism had tended to be perceived as a single, more-or-less uniform entity: “Now, however, we realise that there are at least three orders of republicanism.”

Craven divides most of the Republican delegates into one of three categories: “democratic Republicans”, or as he prefers to call them, “radical Republicans”, “conservative Republicans”, and “symbolic Republicans”, described by Craven as “mainstream Republicans”, and whom I have sometimes chosen to call “official republicans”. Each group had its own claim to a kind of republicanism, but some felt inclined to argue that theirs was the only legitimate expression of republicanism. As Moira Rayner explained: “The republican cause is a broad church. True believers may, and we did, legitimately differ, yet the Australian Republican Movement … claimed orthodoxy and that other views were heretical.”

Democratic Or Real Republicans

The democratic or real republicans were those delegates at the convention who embraced constitutional reform but saw it as not merely symbolic in nature. Rather, the symbol of a new political order was to gain significance from the other substantive reforms it heralded for the people. Many of these delegates combined to form a loose coalition, the “Direct Election of the President Group”. But for many, a directly elected president transplanted into a Westminster system was not really enough. Often, the aim was an executive presidency. These people were attempting to reform the system rather than merely redecorate it. They have united under the name “Real Republicans” to fight for a No vote in the 1999 referendum. They, even more than con¬stitutional monarchists, attracted the ire of the official republicans. For example, former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam called them “irresponsible and ignorant”. (Australian Financial Review, 26 May 1999)

The democratic republicans were quickly robbed of any real opportunity to discuss their concerns. As John Uhr explains their predicament:

John Howard justified his Convention as a way of broadening the agenda of constitutional change from the head of state to other issues of great constitutional significance, such as parliamentary terms, Commonwealth—State relations and the allocation of legislative and executive powers. Sadly, the Convention was given a much narrower brief, which pushed to the side any constructive deliberation on related issues of democratisation and constitutional modernisation.

This was a great problem for those who, unlike the official Republicans, were not interested merely in symbols. These included Moira Rayner and the Reverend Tim Costello. Rayner says: “We … argued that the head of state was an unimportant symbol … We had always said that the head of state issue was less important than our democratic and constitutional problems.”

They were joined by a vocal minority, including Sydney Magistrate Pat O’Shane (who wanted not “just a republic” but “a just republic”), Western Australian Professor Patrick O’Brien and the teams mounted by former Brisbane Labor Lord Mayor Clem Jones in Queensland and former independent MP Ted Mack in New South Wales, to lobby for a directly elected president.

The discussion was not completely limited to minimalist change. John Uhr notes that much of the debate, and indeed the final communique, “strayed beyond these narrow confines” almost as a kind of proof that the popularly elected delegates would not be prevented from raising a wider range of issues for constitutional change.

Those hoping for reform, like Uhr, must remain profoundly disappointed with the convention’s outcome. For this, he blames a “sceptical” prime minister who had won a victory that promised to make an Australian republic safe for the prevailing interests that dominate the Australian parliamentary government. “The preferred option leaves most of the crucial decisions in the hands of the ruling prime minister. Thus a conservative prime minister has the prospect of bringing home Labor’s minimalist bacon.” He seems to have forgotten John Howard is opposed to the model.

Richard McGarvie and the Conservative Republicans

The conservative Republicans (perhaps we should call them “neo-monarchists”) remained a force after the Democratic-Republicans had been vanquished. This group comprised the delegates attracted to the model proposed by a former Victorian judge, then Governor Richard McGarvie. McGarvie acknowledged that the queen plays a real role in the constitution, one that a genuinely minimalist Republican must seek to replace with a new institution. They proposed establishing a council of retired statesmen and jurors to appoint the president on the prime minister’s advice.

Craven says that the conservative republicans have more or less “reluctantly” embraced the Australian republic as inevitable but are vitally concerned to ensure that the new republic clings as closely as possible to the underpinnings of its monarchical ancestor. (Yet early in the referendum campaign, Craven moved to support the so-called bi-partisan model that is the subject of the referendum – the second Keating–Turnbull republic.)

These are Australians who are willing to contemplate an Australian republic so long as it represents merely “an indigenous adoption” of Australia’s highly successful system of constitutional monarchy.

Professor Winterton says that McGarvie is misguided in thinking that his constitutional council is any real substitute for the crown. He overlooks the important consideration that a head of state must enjoy “some legitimacy” for the effective performance of the functions of the offices, including both the symbolic role of national figurehead and focus on national unity and the exercise of reserve powers to protect the constitution if necessary. The governor-general’s legitimacy derives from the representation of the crown, which enjoys a legitimacy derived from history, tradition, sentiment and, for some, religion.

But, Winterton asks, what reserve of popular authority could a republican head of state chosen by a prime minister and appointed by a constitutional council draw upon when necessary to dismiss a prime minister or premier commanding the solid support of the lower house of parliament? Australia’s political culture is, he says, “too egalitarian” to place much credence in a constitutional council of retired judges or retired heads of state. Moreover, while the “majesty and respect” enjoyed by the monarch may constrain an Australian prime minister in nomi¬nating a candidate for governor-general, it is difficult to envisage the proposed constitutional council fulfilling a similar function, so that the council’s alleged equivalent with the monarch is “unsustainable”. (Adelaide Review, August 1997)

Unlike the symbolic Republicans, the conservative Republicans are concerned about retaining the monarchical skeleton even if it is encased in a Republican shell. Professor Craven says that the existing system is not, as is sometimes supposed, unadulterated in character. Our democracy is fundamentally qualified. It is both “representative” and “parliamentary” in nature so that the will of the people cannot legitimately be expressed directly and immediately but only through the prism of their constitutionally elected representatives. This essentially conservative British version of democracy was, he says, directly confronted at the convention by the “spectre of a popularly elected president” wielding popular power in defence of the electorate against its parliamentary representatives. So, he says, the real Republicans were at odds with everyone who stood by a more traditional concept of Anglo-Australian constitutional theory. Craven suggests that the real dilemma for conservatives is one about how best to preserve the democracy they presently enjoy rather than one about republicanism versus monarchy.

The conservative Republicans exerted a greater influence over the official ARM Republicans than the democratic Republicans were able to do. This was principally because of a media campaign to tempt the ACM and its allies to vote “strategically”. This strategy was to support the McGarvie model as the “least worst” republic so it would emerge as the preferred model at the convention. The strategy then would be to campaign against the model at the referendum as the easiest one to defeat. The ARM would not believe ACM’s protestations that they were determined to resist this temptation. So, they saw the need to win over at least some democrat republicans and conservative Republicans by changing their model.

Official Republicans – Australia’s Republican Movement (ARM)

This group of Republicans included the dominant voice at the convention, the Australian Republican Movement. The group differs from the conservative Republicans (and to some extent the democratic or real Republicans, too) by “ardently desir[ing] dramatic change in Australia’s symbols”. They also differ from the democratic republicans (and to some extent find common ground with the conservatives) by claiming not to seek to change the “substantive systems of government”. The difficulty is that they either do not know what they are doing or they are not letting on that they want to make significant changes to the Constitution. Both of their models are substantially different from the present constitution.

Yet this is the school of the so-called “minimalists”, the heirs to the Keating legacy. It had the numbers to largely control the Republican vote at the convention, provided the monarchists did not vote “strategically”. The model endorsed by this group was the one that popped up in the last days with a nomination procedure tacked on as an apparent peace offering for the Democratic-Republicans and an amended dismissal procedure to attract the conservative Republicans and the Labor Party. In other words, just another deal behind the scenes to get the maximum vote.

There are many critics of this group’s final model. Professor Winterton, himself a delegate of the symbolic republic persuasion, explains that the convention’s failings are largely attributable to two factors: insufficient attention was devoted to the details of the republican model, and the ARM conceded too much to the prime minister and to supporters of the McGarvie model in “a futile attempt” to secure their support.

Besides criticisms of their tactics, some highly informed commentators began to question the fundamental tenets of the minimalists’ approach at the convention. Professor Cheryl Saunders has said that, in hindsight, minimalism was a mistake. It has encouraged Australians to think in terms of retaining unnecessary monarchical forms while replacing the monarch.

This approach resulted in a first model where the substance is monarchical and the symbolism republican. This is as intolerable to those who want substantial reform as it is to those who believe the existing machinery works well and should not be jeopardised. Moira Rayner writes that if the referendum succeeds, we will enter the twenty-first century with “twentieth-century amendments cobbled onto a nineteenth-century constitution which is dressed up with a poetic, meaningless preamble”. She describes this as “the sweet smell of democratic decay masked with the synthetic scent of eucalyptus”.

The official ARM Republicans, despite their numbers, influenced few others. Their so-called symbolic changes were anything but that. They would work to the detriment of the existing system of checks and balances, which is so important to all other delegates! Furthermore, they were unable to provide the kinds of reform desired by the democratic republicans. However, their program did have an initial appeal for those people in society who sense the desirability of change but have not yet considered the details or implications.

THE COMMUNIQUE

The convention’s final resolutions were compiled into a commu¬nique given under the hand of the Chairman, Ian Sinclair, and the Deputy Chairman, Barry Jones, to the prime minister pending the compilation and tabling in parliament of a report of the convention. In Principle Support for a Republic, The convention resolved that it supported “in principle, Australia being a republic”. This was hailed by Republicans as a decisive victory. But as Sir Harry Gibbs points out, since there are many republican models, some of which may be attractive but others which would be regarded by Australians as entirely unacceptable, it is “futile to say that Australia should become a republic” unless an acceptable model fora republican constitution is at the same time suggested. A resolution drafted in the way this one was reflects sentimental preferences but covers up divisions. It was so lacking in meaning that every delegate could have, in good conscience, supported it.

The convention then resolved that the “Bipartisan Appointment of the President Model” be adopted “in preference to there being no change to the constitution” and that the required changes “be put to the people in a constitutional referendum”. It was resolved that this referendum should be held in 1999, and if carried, the new republic should be instituted by 1 January 2001.

The States

The communique adopts a view never before advanced, that the crown is seven crowns and that each can be dismantled piece by piece. So, the convention resolved that the commonwealth parliament and executive should consult their state counterparts to determine whether the adoption of a republican system by the central government would have any implications on the state’s constitutional arrangements. It was also resolved that change at the commonwealth level should not pressure the states to make any involuntary changes, and provision should be made to allow for any state that wished to retain their monarchical arrange¬ments for the time being. All the states will not be required to change at the same time as the commonwealth.

As Sir Harry Gibbs explains, problems may arise from the convention’s treatment of the states:

It would be absurd and destructive of the symbolic significance which Republicans attach to the change if some states remained monarchies when the Commonwealth became a republic. Further, such a situation would give rise to constitutional questions as yet unresolved, including the question of whether the change could be made without the assent of all states. It is a matter of controversy whether a referendum carried only in a majority of states would suffice for this purpose. In any view, the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (1900) would require amendment, and one view is that this could not be done by way of s128 of the Constitution. From every point of view, if Australia is to become a republic, the Commonwealth and the states should change together.

Julian Leser, the youngest convention delegate, warned that in a situation where a majority of votes is achieved overall and in the requisite four, but not all six, states, the high court may be required by the other two states to adjudicate on the constitutionality of the act. He says that the high court could be placed in “an invidious position”. If it decided to make those declarations, it would be forced to ignore the will of the majority of people and the majority of people in four states. Conversely, if it did not make those declarations, it would force the two remaining states into a federal republic that they did not want – it would be ignoring the sovereignty of the people of those states. “The worst scenario for republicans who argue that a republic will bring Australians together is a high court challenge that will tear Australia apart.” It should be noted that the high court cannot give an opinion on the constitutionality of proposed legislation in advance. (In re Judiciary and Navigation Acts, 1921, 29, CLR, 257)

The Bipartisan Model

This was the model that prevailed over the others, such as direct election or appointment by the constitutional council on the prime minister’s advice. It only had the support of 73 of the 152 delegates. It consists of four components: a nomination process, appoint¬ment by a joint sitting of parliament, dismissal by the prime minister and that the president’s powers be those of the governor-general.

The Preamble

Going beyond its terms of reference, the convention resolved that a new preamble should be inserted in the Constitution. The preamble to the Imperial Act is to remain, but any spent covering clauses are to be removed while any remaining operative will be moved into the constitution itself. This will presumably have the effect of limiting the content of the Imperial Act to the preamble, followed by the Constitution, which will commence with a second preamble.

Eleven elements are stipulated for inclusion in the new preamble, ranging from a reference to “Almighty God” to an “affirmation of respect for our unique land and its environment”. Three other matters are listed for possible inclusion. The most curious element is that the preamble is to be drafted “in such a way that it does not have implications for the interpretation of the constitution”. As if that were not enough, Chapter II of the constitution (dealing with the Judicature) is to contain a new provision: “That the preamble not be used to interpret the other provisions of the constitution.” It is not clear that this would be effective, especially in international forums.

On this, Alex Reilly argues that it is illogical to support the expression of core values in a preamble and then to ensure that they are not constitutionally enforceable: “In one breath, the pre-amble pronounces values to aspire to, and in the next it ensures that those values are unenforceable in the interpretation of the constitution.”

What was the intention? Mary Delahunty, an ARM delegate, described the preamble just as a “welcoming mat” for the constitution. Craven suggests that some delegates had a more sinister inten¬tion. He says that the “constitutionally literate” among the radical Republicans had no illusions about the process in which they were engaged. They hoped that the inclusion of rights and values in the preamble might provide “a right-minded high court” with a base from which to interpolate those concepts into the body of the Constitution.

Sir Harry Gibbs is critical of the whole project, explaining that a constitution should prescribe the method of government, and an expression of social values is out of place in such an instrument. It is particularly unwise to attempt to give constitutional recognition to contemporary values since the most elementary knowledge of history should show how dramatically values can change in a comparatively short time … It cannot be predicted with certainty whether those provisions would be used, with unpredictable results, in international tri¬bunals as an indication of the principles which Australia, having recognised, should apply in practice. Despite this, Winterton maintains, “The convention’s resolution on the preamble is one of its most significant, and least timid, accomplishments.”

Even if not for Winterton’s reasons, the preamble resolution is highly significant. It exhibits a desire to make sweeping gestures that have no substantive effect. But there was urgency, and due attention was not paid to the detail – wherein the devil lies. In these senses, it seems to exhibit more transparently the symptoms present in the resolutions regarding the bipartisan model.

In any event, the convention’s proposals were not accepted by the prime minister, who established a separate process, which will be the subject of a separate referendum.

Consequential Changes

The convention also passed resolutions on a number of conse¬quential issues: the name “Commonwealth of Australia” be retained; the use of the title president; new oaths; commencement date of new provisions; various provisions regarding the presi¬dency; provisions regarding monarchical symbols; and eligibility for the presidency. It says that Australia will remain a member of the Common¬wealth of Nations in accordance with the rules of the Commonwealth.

Ongoing Constitutional Review Process

The convention resolved that a provision be made for a mandatory convention to be held three to five years after the refer¬endum is carried, with the purpose of reviewing “the operation and effectiveness of any republican system of government introduced by a constitutional referendum” and to address a broad range of issues. Irrespective of the desirability of another intervention (there were many issues that could not be discussed at this one), making provision for reviewing the system is no compensa¬tion for getting it right the first time. If the 1999 referendum is carried, there is no reason to assume a subsequent referendum to correct the mistakes in the first one would be carried. It will be hard enough to get one referendum through, let alone two.

National Symbols

Attention was drawn to the fact that although consideration of the Australian National Flag and Coat of Arms fell beyond the convention’s terms of reference, some delegates raised the possibility of enshrining both in the constitution.

Definition of Presidential Powers

The convention effectively avoided this issue by resolving that the powers of the new head of state should be the same as those of the governor-general. To this end, the constitution would spell out the non-reserve powers as far as practicable, and a new provision would be inserted stipulating that “the reserve powers and the conventions relating to their exercise continue to exist”. This provides two problems, as we have seen. Firstly, the conventions of the crown could be less effective or disappear. Secondly, the new clause saving the conventions would effectively make them “justiciable” (i.e. reviewable by the court). As Sir Harry Gibbs observes:

If a provision to this effect is written into the Constitution without qualifications, it will fall to the courts to decide what the constitutional conventions require. This would render an exercise of the reserve powers open to legal challenge, whereas at present, those conventions are not open to judicial review. So, a constitutional crisis could drag on for months.

THE PROCESS AFTER THE CONVENTION

The Bipartisan Model was the result of the ABM trying to wrestle with great questions of constitutional law and political theory. It took no more than four days of discussion and negotiation, sup¬ported by many millions of dollars of taxpayers’ funds. But it actually failed on the floor of the convention. Nevertheless, it was the preferred model of the Republican delegates. Accordingly, the prime minister decided that it should be put to the people in a referendum, a view supported by a majority of delegates and by all of the major political parties.

But in what form? Professor Winterton suggested that the “Parliament should generally honour the convention’s resolutions”. This is surely not good enough. In a speech given on 27 March 1998, Sir David Smith warned against federal ministers changing the convention model in the parliament. The people should be allowed to vote on the Republicans’ preferred model:

After describing the final republican model as “a hybrid on a hybrid on a compromise” and after referring to elements of it that he believes are unworkable, Peter Costello was reported as vowing he will urge the Federal Parliament to amend the model produced by the Convention. Other reports spoke of Daryl Williams tinkering with the model during his Department’s drafting of the referendum Bill. For the Government to allow the Treasurer and the Attorney to produce their own version of what they think the Constitutional Convention should have come up with, or for Parliament to tolerate such action, would be a betrayal of the Convention and a repudiation of the Prime Minister’s undertaking. I hope that the community debate that lies ahead of us will be aimed at keeping the bastards honest.

A feature of the convention was a moving address by ACM’s Queensland delegate, Senator Neville Bonner”.

Senator Bonner added a funeral. Chant to a draft by Professor David Flint on the theme, ‘How dare you?’

Error: No videos found.

Make sure this is a valid channel ID and that the channel has videos available on youtube.com.