The Crown has been an established component of the Australian constitutional system since the country’s inception. Despite facing challenges such as the Second World War, it has endured and continues to serve as a crucial mechanism for checks and balances. The current campaign by the Republican party marks the fourth major effort to eliminate the Crown’s role, but its integral place in our language and culture cannot be denied.

The first significant Republican movement was in the nineteenth century. Its aim was to establish a white racist republic free of the immigration policy of the British Empire. This faded away with the movement to the Federation, with the Commonwealth of Australia endowed with an express power to establish a national immigration policy.

Left to right: Peter Fraser (New Zealand), John Curtin, Winston Churchill,

King George VI, William Mackenzie King George entertained Dominion leaders at Buckingham Palace in 1944

Left to right: Peter Fraser (New Zealand), John Curtin (Australia), Winston Churchill Great Britain), King George VI, William Mackenzie King (Canada), Jan Smuts (South Africa).

The second and longest campaign was to create a communist state similar to the East European Peoples’ Republics established after the Second World War. Its proponents never made the slightest impact in Australia electorally, notwithstanding their control of several key strategic unions.

The third was initiated by the Australian Republican Movement and promoted by Paul Keating when he was Prime Minister. Its object was to graft onto the constitution a republic, but initially only at the federal level. In this republic, the president would be appointed by parliament. Although a string of implausible reasons for the change was advanced by senior Republican figures, ranging from reducing unemployment and the brain drain to stopping Australian expatriates from being taken for Britons, the raison d’être of their campaign was that only a republic could provide an Australian Head of State.

Their formidable political and media campaign culminated in the 1999 referendum, which was defeated nationally and in all states. The Republican movement said that whatever the result in 1999, it would close down. However, it has mounted the present and fourth campaign for an Australian republic.

The significant differences now are. First, the movement is unwilling or unable to specify the model or any details of the change it wants. Secondly, the movement calls for holding a plebiscite or, according to one faction, two plebiscites

The Early Years

The more radical form of nineteenth-century Australian republicanism is distinguishable from the conservative tradition by its emphasis on nationalism. Dr Mark McKenna argues that this is a Labor tradition. But it was broader than that, and not all those associated with Labor were Republicans.

Indeed, all Australian Labor prime ministers were monarchists, with the exception of Bob Hawke – an indifferent Republican in office, and Paul Keating. (Gough Whitlam became Republican after, and probably because of, his dismissal.) The best-known early nationalist Republicans came to prominence well before the birth of the Labor Party. Today, many official Republicans seek to frame republicanism as a choice between Australian independence and fealty to the former mother country.

This was certainly Paul Keating’s position, and it was also true of the radical nineteenth-century Republicans, at least until the end of the transportation of convicts and the rise of responsible government in Australia. The first noteworthy great republican figure of the nineteenth century was undoubtedly the Reverend John Dunmore Lang, a minister of religion. He also had the habit of collecting money from new immigrants on the basis that they would immediately receive land grants. They did not. As a result, he was sent to gaol- until his supporters raised sufficient funds to release him.

Needless to say, this did not help the reputation of the Republican cause. The Sydney Morning Herald described Lang as “arrogant, intolerant, and a scheming charlatan”. NSW Premier Sir Henry Parkes and other colonial leaders soon saw that linking republicanism to self-government would be fatal. They distanced themselves from Lang, who attempted to reform his Republican League, with a targeted membership of 10,000.

A public meeting was called on Australia Day 1854 for the launch, but only thirty people attended. Lang’s bleak Republican dawn brings to mind Tony Abbott’s comment that some of the 1993 public meetings across the country called by Paul Keating’s Republican Advisory Committee (with generous taxpayer funding and with all those Republican celebrities) could have been held in a telephone booth.

A White Republic

We received an email from a student doing research on ‘Why didn’t Australia become a republic in 1901’. The student asked for assistance “in understanding Australia’s resistance to forming a republic in 1901”. We pointed out that the way in which the colonies united to form our nation was unique in that it was not only debated in the mainly elected conventions but was actually approved by the people. Unlike the United States, we have verbatim records of all the debates in several conventions and voluminous records of public consultations and discussions.

There is no record of any “resistance” to a republic – it was not an issue. There was a consensus that the new parliament would operate under the Westminster system with the Crown at the centre of the constitutional system.

The only significant republics in the world at that time were France, the United States and Switzerland. The latter two had been through civil wars that century, and France had experienced several violent changes in the regime. The British seemed to be the most advanced system, for it combined stability with democracy under the rule of law. It had been copied not only in the British Empire but also in Europe.

The time when republicanism was an issue in Australia was not at the Federation, but some decades before. This began around the time of the gold rush when a movement developed for a white Australian policy. But the British imperial authorities were opposed to any discriminatory immigration policy. So the more radical thought this could only be achieved by secession as a white republic.

An influential journal, The Bulletin, led this movement. This was founded by J.F. Archibald, who financed the magnificent fountain bearing his name in Hyde Park, Sydney. For a small population, the circulation of the journal was very high and, at times, reached around 80,000. The motto on the journal’s masthead was “Australia for the White Man”, a motto which still existed until it was taken over by Sir Frank Packer in 1961.

Interest in a separate white racist republic waned with the movement to the federation. Among the powers of the new Parliament was one over immigration. To try to circumvent British displeasure with the White Australia Policy, a South African-style discretionary dictation test was introduced.

Republicans today are embarrassed when it is pointed out that their most significant predecessors were those in the nineteenth century who were principally interested in a racist republic and those in the twentieth century who wanted to impose a Soviet-style peoples’ republic onto the nation.

A Very Racist Republic

While there is a strong nationalistic republican tradition in early Australian history, it would seem curious that there is little reference to this by contemporary official republicans who nevertheless loudly appeal to patriotic sentiments.

The reason is simple: many early patriotic Republicans embraced embarrassing doctrines. Late nineteenth-century republicanism was dominated by the leading Australian journal at the time, The Bulletin. In 1888, 40,000 people attended an anti-Chinese demonstration in the Sydney domain.

The Bulletin said, “Australia had to choose between independence and infection, between the Australian Republic and the Chinese leper”. The Bulletin wanted an Australian form of ethnic cleansing: the expulsion of all Asians. Little is said of these antecedents within the present Republican movement. Certainly not from Robert Hughes, the Australian-born critic of Time magazine, who, at a rally in 1996, tried to draw some tenuous link between our constitution and racism.

He clearly overlooked nineteenth-century Australian republicanism.

The Bulletin attacked Joseph Chamberlain, the British colonial secretary when Royal Assent refused the Queensland Sugar Works Guarantee Amending Bill, which banned coloured labour.

On 22 June 1901, the year of federation, The Bulletin observed: “If Judas Chamberlain can find a black, or brown or yellow race…. That has as high a standard of civilisation and intelligence as the whites, that was progressive … as brave, as sturdy, as good nation-building material, and that can intermarry with the whites without the mixed progeny showing signs of deterioration, that race is welcome.”

The Bulletin’s racism was to linger well beyond its republicanism. Only within living memory did it suppress the motto on its front page masthead: “Australia for the White Man”.

It is true that there were attempts by the Labor movement in the 1880s to link the maintenance of monarchical institutions with the persistence of social inequality in Australia. But by the end of the next decade, when Labor politicians began taking their seats in the colonial parliaments – not to mention their oaths of allegiance – it became apparent that reform could best be encouraged through the existing institutions.

It was generally agreed that the monarch was no obstacle to reform. The Brisbane-based Boomerang, for instance, explained in 1890 that:

“Unless republicanism is thoroughly progressive and democratic practically, as well as nominally, we might as well remain exactly as we arc, Because we are discontented with King Log we do not want to place ourselves in the hands of President Stork … The republic we want is a land of free men whereon the government rests on the people, and is by them with them and for them. No other form of republicanism will suit us not even though it does a few who follow the will-o-the-wisp of a mere name.”

Mark McKenna concludes that the Labor movement realised that Australia’s monarchical institutions were as amenable to social democratic government guaranteeing equality as they were to the laissez-faire capitalist policies of the conservatives.

It became equally apparent to that most nationalistically republican of journals, The Bulletin, that abolition of the monarchy was no longer a practical necessity.

It conceded that the monarchy was practically unobjectionable so long as it was understood that the British monarch held his or her position by the nation’s will and for the nation’s convenience.

Federal Conventions: Only One Republican Delegate

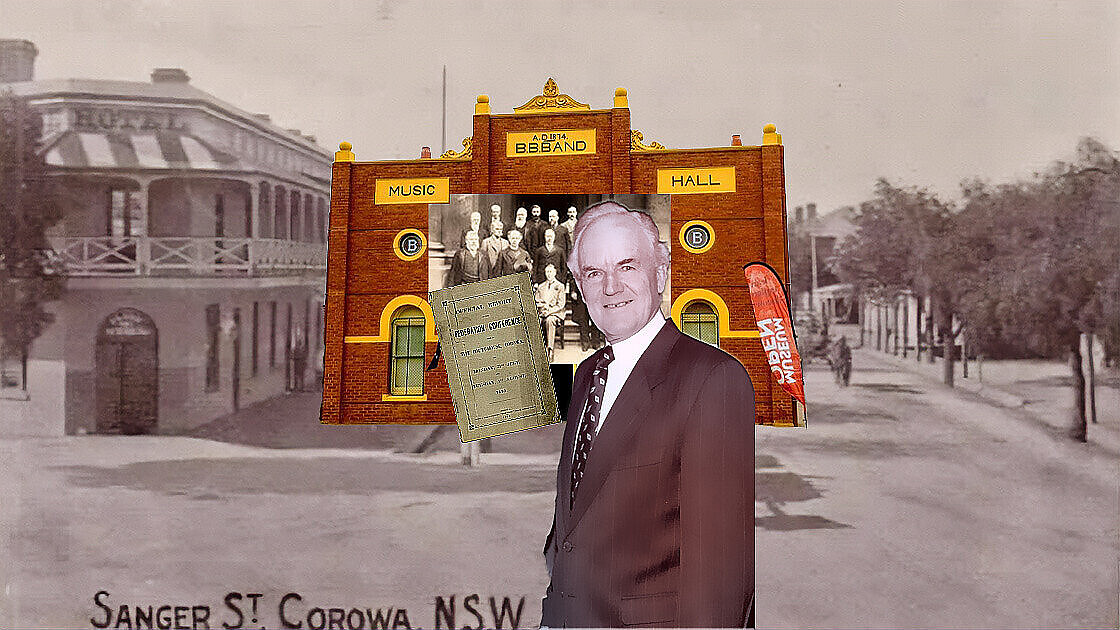

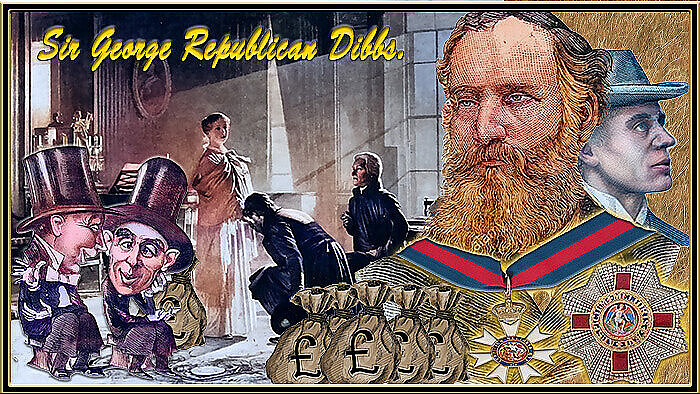

In fact, only one delegate at the nineteenth-century constitutional conventions argued for the end of the monarchy. He was George Richard Dibbs, the Premier of New South Wales. When he visited London, he accepted a knighthood. The Bulletin referred to him as Sir George Republican Dibbs.

Sir George Richard Dibbs KCMG (12 October 1834 – 5 August 1904) was an Australian politician who was Premier of New South Wales on three occasions. He became Premier on 17 January 1889 but was succeeded by Parkes seven weeks later. When Parkes resigned in October 1891, Dibbs came into power following the 1891 New South Wales election, with Labour support, in a time of great financial stress. He went to England in June 1892 on a borrowing mission, not only as the representative of New South Wales but also of Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania, and carried out his negotiations successfully. During the banking crisis of May 1893, he showed himself to be a firm leader, saving the situation in Sydney by giving the banks the power to issue inconvertible paper money for a period. However, most of them failed to take advantage and went bankrupt. In 1893, his electoral reform removed rural over-representation. He was elected as the member for Tamworth in 1894. He later received a substantial public testimonial for his services at this time. He was made a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) in July 1892.

Banjo Paterson wrote a ballad of GR Dibbs:

This is the story of G.R.D.,

Who went on a mission across the sea

To borrow some money for you and me.

This G. R. Dibbs was a stalwart man

Who was built on a most extensive plan,

And a regular staunch Republican.

But he fell in the hands of the Tory crew

Who said, “It’s a shame that a man like you

Should teach Australia this nasty view.”

From her mother’s side, she should ne’er be gone,

And she ought to be glad to be smiled upon,

And proud to be known as our hanger-on.”

And G. R. Dibbs, he went off his peg

At the swells, who came for his smiles to beg

And the Prince of Wales — who was pulling his leg

And he told them all when the wine had flown,

“The Australian has got no land of his own,

His home is England, and there alone.”

So he strutted along with the titled band

And he sold the pride of his native land

For a bow and a smile and a shake of the hand.

And the Tory drummers they sit and call:

“Send over your leaders great and small;

For the price is low, and we’ll buy them all

With a tinsel title, a tawdry star

Of a lower grade than our titles are,

And a puff at a prince’s big cigar.”

And the Tories laugh till they crack their ribs

When they think about how they purchased G. R. Dibbs.

The Bulletin, 27 August 1892.

The realisation that there is little or no reason to complain about a monarchy that is there only as long as the nation wants it, and holds its powers in trust for the nation has been expressly acknowledged by Queen Elizabeth herself at her golden wedding celebrations at the Guildhall in 1997:

” … an hereditary constitutional monarchy exists only with the support and consent of the people. “

Australia’s ‘nineteenth-century republicanism, while it lasted, was overtly racist, based on a narrow, isolationist and exclusive image of Australia as a white man’s land. It was motivated by a fear of Asian immigration.

And these Republicans were also dismissive of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Mark McKenna concludes, “There is no heroic pantheon of republican antecedents in Australia.”

The second republican movement: bolshevism

By way of contrast with Australia’s first republican movement, the earlier twentieth-century republican movement, from the First World War until about the sixties, was at most times not racist. However, its allegiance was certainly not to the Crown but rather to a foreign government.

That allegiance was wholly and totally to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the name of the old Russian communist empire. The members and supporters of the Communist Party of Australia denounced and sought to undermine the Second World War while Stalin was in alliance with Hitler, with a secret deal on how to partition Poland.

When Hitler turned on Stalin, they declared war just. This did not stop them from actively sabotaging the war effort when they saw it advancing their aims and when such sabotage did not damage their beloved USSR. The USSR gave the Party not only its direction but also substantial financial assistance.

The Party did not achieve any significant electoral support in Australia, never winning a seat in the federal parliament, even with their apparent support for the war and talk of a united front, the Stalinist tactic at the time.

But they managed to occupy commanding positions in the trade unions, particularly those of strategic importance to the defence of the Commonwealth. Although against the rules, they sought to infiltrate the ALP and influence it. The damaging post-war split in the ALP and the formation of the Democratic Labor Party was a result.

A communist republic

Before the split, the ALP Industrial Groups in the union movement were the only significant opponents of communist control. Heavily influenced by the Catholic Church but not exclusively Catholic, they gradually removed the communists from a large number of trade unions.

In fact, it was a renowned constitutional monarchist, Dr Frank McGrath (formerly His Honour, Mr Justice McGrath), who was instrumental in breaking the grip of the communists on the Federated Ironworkers Association. This seemed to contradict the story that the late Whitlam government minister, Jim McClelland, had actually done this.

According to Frank Rooney, a prominent anti-communist trade union leader, Jim McLelland was never part of the team and came into the picture only after the battle had been won. Then, a young articled clerk, Frank McGrath, was working with a firm of solicitors in 1951 in a challenge to a recent union election.

During the hearing, he signalled to the junior barrister, later Governor-General Sir John Kerr, that he had discovered something. With the aid of the rays of the sun streaming into the courtroom, a number of impressions of “ticks” clearly came through on the disputed ballot papers tendered as evidence. Obviously, stacks of blank ballot papers were being filled in by one person at a time.

Frank McGrath was to spend days in the witness box. On the strength of his evidence and that of handwriting experts, Mr Justice Dunphy found that Laurie Short had actually been elected as general secretary and that new elections for the other offices must be held. (This story is told in Frank Rooney, Dictators within the Labor Party of Australia, edited by Dr Amy McGrath, Towerhouse Publications, Sydney, 2005 )

Unlike today’s Republican movement, the communist Republicans did not pretend they had no model. They wanted to turn Australia into a workers’ paradise – a people’s republic on the East European model. They never explained why people were always trying to escape from, and not into, their peoples’ republics.

Australia’s second republican movement was long subsidized by and under the instructions of the Soviet Union. Without the Soviet Union, it would have been impoverished and directionless. It is unlikely that it would have been able to occupy the positions of significance it did in the trade union movement and in political life.

Communism and monarchy

It is interesting to speculate what would have happened in Russia had not the German High Command smuggled Lenin in a sealed train into Russia with the intention of weakening and neutralizing the Russian Government.

When the Bolsheviks eventually seized power, it could not have been said they had a popular mandate. But with power, they were able to change Russia.

Had they not come into power, there would have been no significant Communist Party of Australia and no second Republican movement. So, how did the Tsarist system compare with the subsequent Soviet regime? Were the Soviet republics, as we were constantly told, a great improvement?

Oleg Gordievsky is one of the highest-ranking and most valuable KGB defectors. He was a Colonel of the KGB and the bureau’s rezidentura in London but became disillusioned with the Soviet system.

He defected to the United Kingdom in 1985. In a letter to The Independent on July 21, 1998, he wrote:

“Russia under Nicholas II, with all the survivals of feudalism, had opposition political parties, independent trade unions and newspapers, a rather radical parliament and a modern legal system. Its agriculture was on the level of the USA, with industry rapidly approaching the Western European level. [In contrast] in the USSR there was total tyranny, no political liberties and practically no human rights. Its economy was not viable; agriculture was destroyed. The terror against the population reached a scope unprecedented in [human] history. No wonder many Russians look back at Tsarist Russia as a paradise lost.”

Can you imagine what our second Republican movement could have done with Australia?