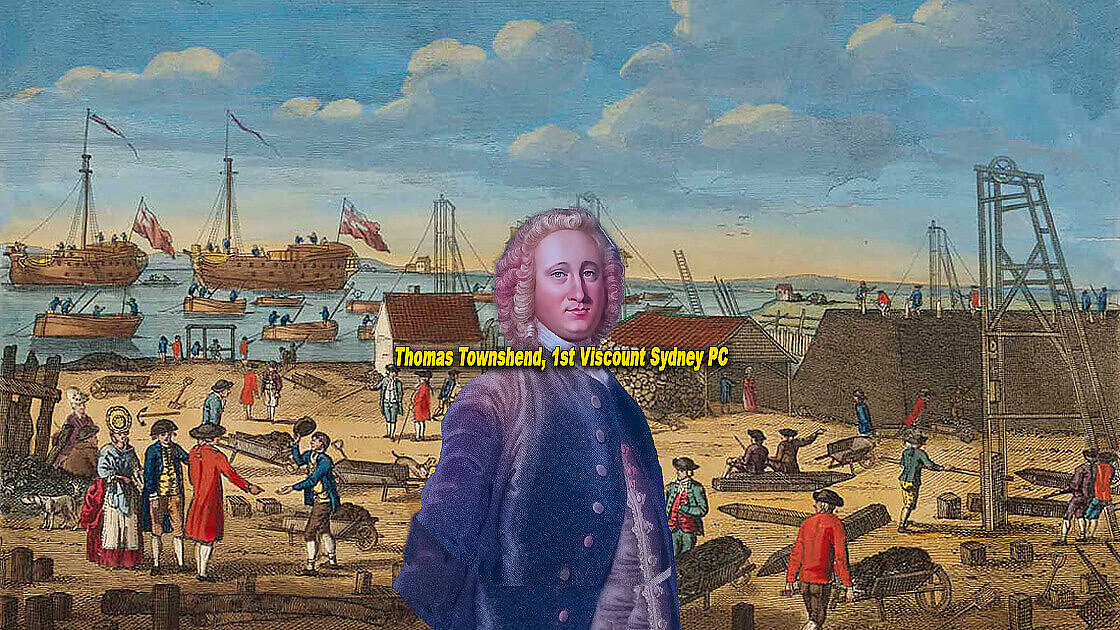

Thomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney PC (24 February 1733 – 30 June 1800) was a British politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1754 to 1783 when he was raised to the peerage as Baron Sydney. He held several important Cabinet posts in the second half of the 18th century. The cities of Sydney in Nova Scotia, Canada, and Sydney in New South Wales, Australia, were named in his honour in 1785 and 1788, respectively.

When the British came to Australia, they did not find a country in which there was anything recognisable as a government. They had in other parts of the non-European world, but not in Australia.

To say that is to denigrate neither the Aboriginal history of this continent nor the Aboriginal people. But modern Australia began with the settlement, which had both harsh and good consequences for the indigenous people. Some form of European settlement was inevitable, and the fact that the acquisition was British was, on all historical evidence and comparisons with other places, preferable.

…the rule of law…

Australia has been fortunate in the calibre of so many of those involved in the government of the early colonial establishments. It is worth mentioning Lord Sydney, whom too many glibly dismiss as being of no consequence. He had taken a decision which would have a fundamental effect on the colony. Instead of just establishing it as a military prison, he provided for a civil administration with courts of law.

The rule of law came to Australia from the founding of the colony in 1788.

Lord Sydney’s decision reflected very much the views of the first Governor, Captain, later Admiral Arthur Phillip, who wrote before leaving England: “In a new country, there will be no slavery and hence no slaves.”

Phillip also ordered that Aborigines be treated well and indicated that the murder of an Aborigine would be punished by hanging.

It is good that there seems to be some attempt to recognise the contribution of our first Australian Governor.

A recent example was an important lecture, enhanced by a video presentation, given by a former UK High Commissioner, Sir Roger Carrick, at a function at the American American Club organised by Mr Richard Nott, the President of the NSW Branch of the Australia-Britain Society on 6 March 2007.

The vote of thanks was appropriately moved by Her Excellency, the 37th Governor of New South Wales, Professor Marie Bashir. Her Excellency offered the professional opinion, based on an assessment of his life, that Admiral Phillip’s death was consistent with a stroke and certainly not suicide.

…not a gulag…

The noted historian, Keith Windschuttle, has played a leading role in reminding historians of their need to observe certain elementary standards in their research.

Above all, he has demonstrated the need for painstaking attention to the best evidence before conclusions can be drawn, rather than assuming some conclusion because it is consistent with some fashionable ideology.

In an essay on the subject of our early leaders published in the April 2007 edition of Quadrant, he says that many of Australia’s early colonial leaders were human rights activists “ahead of their time.”

An extract was published in The Australian on 24 March 2007. And in a featured column on the same page, which is not on the web but which may be in the Quadrant essay, Dr Windschuttle wrote:

“The idea that slavery was an affront to humanity that had no place in a free land was part of the original definition of what it meant to be an Australian.

“Unfortunately, in today’s academic climate…very few academic historians discuss these issues…

“Moreover, although NSW founder Arthur Phillip’s original anti-slavery declaration was once well known to earlier generations of students, historians today rarely mention it.”

According to a report in the West Australian of 1 August 2007, Mr Malcolm Turnbull, the then Environment and Water Resources Minister, said:

“It is hard to believe … in our prosperous country, that we were once a gulag, a gulag of the southern seas, a hell on earth.”

Mr Turnbull was announcing that eight convict sites on the National Heritage List would form part of a bid for world heritage recognition of Australia’s convict past. It is possible that Mr Turnbull has come to the entirely mistaken conclusion that the colony was a gulag from his Republican uncle, Robert Hughes.

To speak then of the colony as a gulag, as Republican Robert Hughes does, is completely wrong. The Soviet Gulags were the most brutal, lawless concentration camps for political prisoners.

Even under the broadest definition, few convicts sent to Australia could be called political prisoners. More importantly, the British brought the rule of law to Australia from the very foundation of the colony in 1788.

The Governor, Captain Phillip, came with a Charter of Justice, which, unlike the provisions of the Soviet Constitution, was actually applied.

To say Australia was a gulag is wrong, unfair to both Sydney and Phillip and misleading to students of our history. Just consider one example. A civil action very early in the life of the colony was brought by convicts against a ship captain for theft. The captain was defended on the ground that at common law, felons could not sue.

The court required the captain to prove that the complainants were indeed felons. This he could not do because the records were in England. The action was allowed to proceed.

Can Mr Hughes or Mr Turnbull give us a similar example of litigation by prisoners in a Soviet or Nazi gulag, particularly one where the Soviet or Nazi judges upheld the prisoners’ assertions? Of course, they can’t. The penal colony of New South Wales was one of the most successful experiments in criminal rehabilitation the world has ever seen.

The rate of recidivism, or return to crime, was extraordinarily low, as far as we can tell. The slander on Phillip and the British that New South Wales can be equated with a Soviet or Nazi gulag should be withdrawn before it is taught in the schools – if it is not already presented as the truth.

…the pillars of our nation…

The British brought with them four of the six pillars of our nation. These were our national language, English, the rule of law, our Judeo-Christian values and our oldest institution, which provides leadership beyond politics, the Crown.

All were Australianised and made ours. To them were added the other pillars of our nation.

One was a gift of the British, self-government under the Westminster system.

The final pillar, while given legal effect by the British, was our own. This was our indissoluble Federal Commonwealth under the Crown and under the Constitution.

This was designed by Australians in Australia and approved by the Australian people.

It is right and proper that we not hide our failings and our weaknesses. Perhaps our greatest failings were in racial matters, White Australia, and especially with the Aboriginal people. Let us look briefly at the White Australia Policy.

The most virulent Australian opponent of Asian immigration has surely been the staunchly Republican-journal The Bulletin. On 22 June 1901, it attacked Joseph Chamberlain, who, as Colonial Secretary, had The Twilight of the Elites blocked certain Queensland legislation banning coloured labour:

“If Judas Chamberlain can find a black, or brown or yellow race … that has as high a standard of civilisation and intelligence as the white, that is progressive … as brave, sturdy, as a good nation building material, and that can intermarry with the whites without the mixed progeny

showing signs of deterioration, that race is welcome.

“One of the first laws passed after the Federation instituted the White Australia Policy. Its strongest supporters were the unions and Labor Party. They feared, with some justification then, that the relatively good working conditions achieved behind the tariff wall would be weakened by competitively priced immigrant Asian labour. But the White Australia Policy was not enacted to expel existing Asian immigrants, although this was to be the fate of many of the indentured Kanaka workers from the Pacific. The policy allowed Asian immigrants established here to stay but was intended to stop further immigration. To allay strong British objections, a dictation test in any European language could be administered on entry at the discretion of a customs official.

Yet immigrants still came through. My own maternal grandparents, and their children, arrived in Sydney from Batavia, now Jakarta, in 1917. A dictation test was administered on this occasion in English, fortunately, one of the several languages in which they were fluent. They passed, including my mother, who was still a child.

While the White Australian Policy seems outrageous by our standards today, it was a little different from the barriers to Asian immigration erected in other countries, including the United States and Canada. It is not so different from the immigration policies which are still applied by many countries today, including some of our neighbours, but which are rarely criticised. In any event, it was gradually relaxed after the Second World War and no longer applied in any real sense by the mid-1960s.

Australians can be least proud of the policy concerning the Abo¬riginal people. And with the advent of self-government, the restraining influence of more liberal colonial secretaries and governors was removed.

There is a widespread belief, reported in the media, that the 1967 referendum gave the Aboriginal people, for the first time, Australian citizenship and the right to vote. But they were already citizens. Moreover the right to vote had been granted in a piecemeal way, in four States, at least in law, if not in practice, before Federation.

A secondary purpose of the 1967 referendum was to remove pro¬visions from the Constitution against counting Aboriginal people (then considered mainly nomadic) in reckoning the number of people for electoral purposes. The principal purpose was to give the Federal Parliament the power, with the States, to legislate with respect to Aboriginal people. This referendum was a bipartisan measure and was approved by a record affirmative vote of 90.77%.

This vote was the clearest indication of an overwhelming view among Australians that the Aboriginal people were entitled to be treated as equals to other Australians. The extent to which the Aborigines have today been accorded this status is the subject of considerable debate. The noted French historian and anthropologist Emmanuel Todd (1994), argues that the leading indicator of the degree of acceptance of minorities within a society is the degree of female exogamy. That is, the extent to which female members of the minority marry out of their group.

In Australia, according to John Taylor (1997), the 1996 census demonstrated that 64% of “indigenous couple families” were unions between non-indigenous and indigenous partners. These families were almost evenly divided between those where the mother was indigenous and those where the father was indigenous. This indicates a rate of female exogamy among the Aboriginal people of about 32%.

This is far higher than those minorities which Todd evaluates, including black Americans in the United States (1.3%), Turks in Germany (7%), or Algerians in France (perhaps 23%: that last statistic is probably inflated because French citizens of Algerian descent are treated as French.) This is not an unreasonable test, even if it may encourage a charge that those who rely on it are reviving the assimilationist policies of the past. These statistics must constitute a balance against others which compare adversely to such matters as the health and the life expectancy of Aboriginal people with other Australians.

In any event, it is clear that there is hardly any support for a policy which would be intended to differentiate adversely against the Aboriginal people.

The question remains about the proper assessment of past policies. The final judgement on that, if a final judgement can ever be made in this world, will be made by Australian historians in an objective search for the truth.

Assessments of our past treatment of the Aboriginal people range across a broad spectrum. Expatriate Australians Germaine Greer, Robert Hughes and Phillip Knightley are among the harshest critics.

Robert Hughes says that no country colonised by Europeans has treated its indigenous minority more inhumanely than Australia. This was inserted not into a journal of opinion but into the Official Souvenir Program for the Sydney Olympics, 2000! While it says little about the rigour of Mr Hughes’ survey of centuries of European colonialism, it says much about Australia’s liberal attitudes to freedom of speech.

In a recent critique of the views of those who assent a genocidal intent in and the effect of Australia’s Indigenous policies, Keith Windschuttle (2000) cites Phillip Knightley’s conclusion that Australia was able to get away with a racist policy that bordered on slavery and genocide, practices unknown in the civilised world in the twentieth, century until the Nazis turned on the Jews. Of course, there were bloody disputes brought on by the occupation of land by white settlers, which impinged on the traditional wanderings of the Aboriginal people, some of whom may have regarded the white men’s flocks as legitimate prey.

Certainly, there were individuals and even officials who committed terrible crimes against Aboriginal people. But there is no evidence that the Australian treatment of the Aboriginal people ever approached the barbarity of the Nazi’s treatment of Jews, Gypsies and others, including homosexuals and the mentally ill. In the case of these unfortunates, the Nazi policy was for a “final solution”, a term which in itself strikes at everything that is good in man and in his institutions.

The Nazi policy was for the liquidation, the physical destruction, of all people of a proscribed race or group by agents of the state, aided by the police and the public service in accordance with the decisions and directions of the highest state authorities.

There is no evidence that the crimes committed against the Aboriginal people were ever committed as government policy. And there is overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Indeed from the beginning of the penal colony, the authorities were to insist on the application of the rule of law, at least the criminal law, to all men and women of all races and colours. That this was to be imperfectly applied and that there were to be legal restrictions on Aboriginal people, often for pa¬ternalistic reasons, is a matter of great regret. But it does not equate to some form of Nazism at the heart of white Australia.

The application of the rule of law was demonstrated cogently in the final grave words of the judge when sentencing the white perpetrators of the massacre of aboriginal people at Myall Creek in 1838, over 160 years ago. These words demonstrate that even then, the principle that the rule of law must in Australian society prevail, whatever the race or colour of the victim or offender.

Mr Justice Burton pronounced these words:

“Prisoners at the bar … you have been found guilty of the murder of men, women and children. The circumstances of the murders of which you have been found guilty are of such singular atrocity that I am persuaded that you long ago must have expected what the result would be.

“This is not the case where a single individual has met his death by violent means; this is not the case, as has too often stained indelibly the annals of this Colony, where death has ensued from a drunken quarrel; this is not the case, when, as this session the Court has been pained to hear, the blood of a human being and intoxicating liquor were mingled on the same floor, this is not the case where the life or property of an individual has been attacked, ever so weakly, and arms have been re¬sorted to. No such extenuating circumstances as these, if any consider them extenuating, have taken place.

“This is not the case of the murder of one individual, but of many men, women, and children, old men and babes hanging at their mothers’ breasts, to the number in all, according to the evidence, probably of thirty individuals, whose bodies on one occasion were murdered — poor defenceless human beings …

“I cannot expect that any words of mine can reach your hearts, but I hope that the grace of God may reach them, for nothing else can reach those hardened hearts which could surround that fatal pile and slay the fathers, mothers, and the infants …

“I cannot but look at you with commiseration; you were all transported to this Colony, although some of you have since become free; you were removed from a Christian country and placed in a dangerous and tempting situation; you were entirely removed from the benefit of the ordinances of religion; you were one hundred and fifty miles from the nearest Police station on which you could rely for protection — by which you could have been controlled. I cannot but deplore that you should have been placed in such a situation — that such circumstances should have existed, and above all, that you should have committed such a crime.

“But this commiseration must not interfere with the stern duty, which, as a Judge, the law enforces on me, which is to order that you, and each of you, be removed to the place whence you came and thence to a place of public execution and that at such time as His Excellency, the Governor, shall appoint, you be hanged by the neck un¬til your bodies be dead, and may the Lord have mercy on your souls.”

Recall that this is a judge, in 1838, sentencing white men to death for the murder of Aborigines. What greater evidence can there be of a society under the rule of law for all, and for all races and colours, than these words? And this was in the early part of the nineteenth century. These words are more than sufficient not only to deny but to unmask the unjustified attempt by some to paint our country as a genocidal hell. While our nation is not perfect, Australians have much to be proud of in the history of our Federation.