The 1999 Referendum.

The republican model, the Keating Turnbull republic, was then referred to the people.

This emerged in the last days of the Constitutional Convention. This was the Second Keating-Turnbull Republic, one which was highly authoritarian and anti-federal and which was suddenly pulled out of the hat. After telling us in 1993 that there was an almost universal view that the President was not to hold office at the whim of the Prime Minister, the ARM (Australian Republican Movement) now proposed the first republic in recorded history where it would be easier for the Prime Minister to dismiss the President than his cook! Not developed from the point of constitutional principle, this model was formulated only to procure the maximum votes from the politician delegates so as to obtain a majority vote at the Convention. And it failed even in that.

But as the constitutional model was chosen and preferred by the largest number of Republican votes at the Convention, the Prime Minister honoured an election promise and put that model to the people.

In the resulting campaign in 1999, the Yes case coalition was to come out with at least six conflicting messages.

Mr Malcolm Turnbull and Mr Greg Barns of the ARM (Australian Republican Movement) said that if you voted Yes, there would be no substantial change to the Constitution.

Mr Thomas Keneally, the author and spokesman for the ARM (Australian Republican Movement), said that if you voted Yes, the result would be the biggest structural change to the Constitution since the Federation.

Mr Andrew Robb, former Liberal Party Director and spokesman for Conservatives for an Australian Head of State said that if you voted Yes, you would escape from the horror of ever being allowed to choose the President. You would never have to elect the President, principally because you would never be allowed to do this.

Mr Kim Beazley said that if you voted Yes, he would allow you to decide — at some later time and if he became Prime Minister — whether you would wish to be allowed to elect the President.

Sir Anthony Mason and Mr Jason Li seemed extremely worried by an imagined “rule” that the Governor-General never appears with the Queen. This, they said, proved the Governor-General not to be that Head of State which the Keating Government said he was and held him out to be inferior to foreign governments. (The lack of such a “rule” was exposed by Sir David Smith when he drew attention to an official photograph of a State occasion showing the Queen sitting next to the Governor-General and with Sir Anthony in the group!)

Mr Jason Li also seemed to be promising greater sexual freedom, although whether this would be before or after the republic was installed was not clear.

Out of this cacophony, out of these contradictory acts and voices, there was only one single theme. It was to get rid of the Queen. And, clearly not understand the institution of getting rid of the Australian Crown. At any price.

Even at the price of an unwise, unprecedented, undemocratic accrual of power. Even at the price of constitutional and government instability.

Behind this Yes case was a grand coalition of unusual bedfellows:

- the Australian Labor Party organisation (but not, from the way they voted, many, if not most, of its members and supporters),

- much of the Liberal Party organisation (but not from the way they voted, most of its members and supporters),

- the Australian Council of Trade Unions (but not a significant number of union members),

- about two-thirds of all sitting politicians (State and Federal),

- almost all capital city newspapers,

- much of the Big Business establishments,

- most political journalists,

- a cast of celebrities, and

- above all, great wealth.

Against that, not a lot. Only a band of men and women, almost all volunteers, whose ranks by the 6 November 1999 grew to over 50,000 Australians. Almost a parallel, single-purpose political party! Kerry Jones (2000) proved a superb leader of that campaign, with a rare command of advocacy, political, organisational and financial skills. Unlike the Australian Republican Movement, Australians for Constitutional Monarchy has only had two Executive Directors, Kerry Jones and Tony Abbott. (It has had only two National Convenors, Justice Lloyd Waddy and myself) In contrast to ACM’s grassroots organisation, it was all so easy for the ARM (Australian Republican Movement). For its foot soldiers, all it had to do was ring the Secretaries of the Australian Labor Party and the ACTU.

The Results

When I saw the patently flawed Republican model adopted at the Convention, greeted by the headline “It’s all over bar the voting”, I had expected that the Yes vote in the referendum would have even been lower than that recorded on 6 November. We were subsequently warned that the electoral system would probably make the Yes vote larger than it actually was. First, there is no verification of recent registrations. Secondly, voting is no longer restricted to one polling place, and there is no means of preventing voting in two or, indeed, several places, especially in inner metropolitan electorates where anonymity is virtually guaranteed.

In addition, I did not expect that so many people in politics, the law, the media and elsewhere would throw themselves with such enthusiasm behind such a bad model. I had not expected that so much of the media would so unashamedly campaign for such a flawed model in news columns and broadcasts. Ted Mack, the wise man, foresaw that they would do so. He warned me at Corowa, well before the campaign, that they would do so because so many relished the centralisation and concentration of power that the model offered.

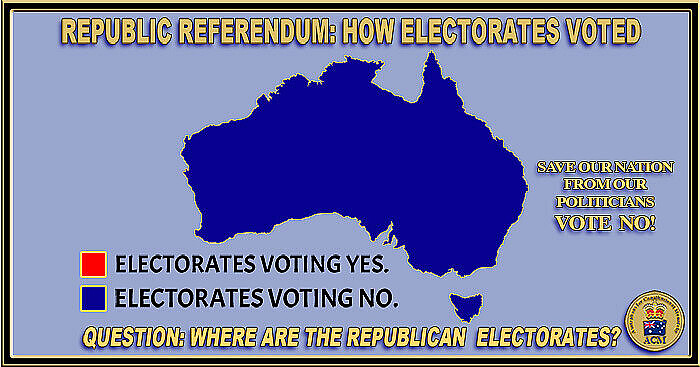

Nevertheless, we in the No case had believed all along that Australians, as Richard McGarvie puts it, are wise constitutional people. We had confidence in the people of Australia. The result was a landslide. Taking into account informal votes, and non-voters, about 43% of the electorate voted Yes. While Republican lawyers assumed that constitutional success for the Yes case required that it capture four states, all six States voted No, and the Northern Territory voted No. Only the Australian Capital Territory voted Yes. (A better view, held by former Chief Justice Sir Harry Gibbs and Richard McGarvie, was that the change was so fundamental all six original states needed to agree.)

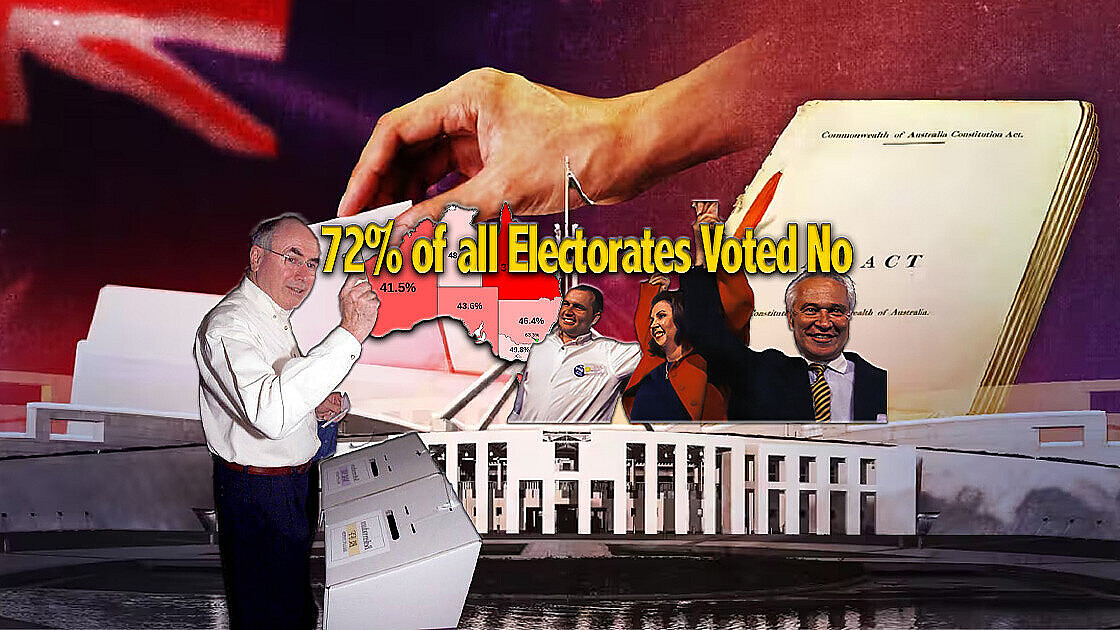

Every regional electorate voted No. Every rural electorate voted No. Every truly outer suburban electorate voted No. Seventy-two per cent, 72% of all electorates voted No. In South Australia, 75% of electorates voted No. In Tasmania, 80%, and in Western Australia and Queensland, 93%!

When I was interviewed on the Sydney Opera House balcony by the BBC early in the evening of 6 November, above the marquees displayed below to welcome Republicans celebrating their victory, I said that it already looked like a landslide. Young Republican Jason Li, who was also being interviewed, looked at me in utter amazement.

The campaigning and its consequences — some personal experiences – By David Flint

After the referendum, Malcolm Turnbull (2000) published his referen¬dum diary Fighting for a Republic (which Julian Leeser said should be renamed Whingeing for the Republic). In it, Turnbull has some harsh words to say about me. Not only am I lacking in humour and a carica¬ture of a monarchist — I also have a “pseudo-British” or a “pseudo-English” accent. I am extreme, untruthful, raising one scare after another. I am not at all a constitutional lawyer (although I have taught and published in the area). Then, on 2 November 1999, Turnbull condoned a very personal attack on me by his campaign director Greg Barns who, he wrote, was clearly in an “if you see a head, kick it” mode. Turnbull justified this because campaigning rationally and courteously had not done the ARM (Australian Republican Movement) much good!

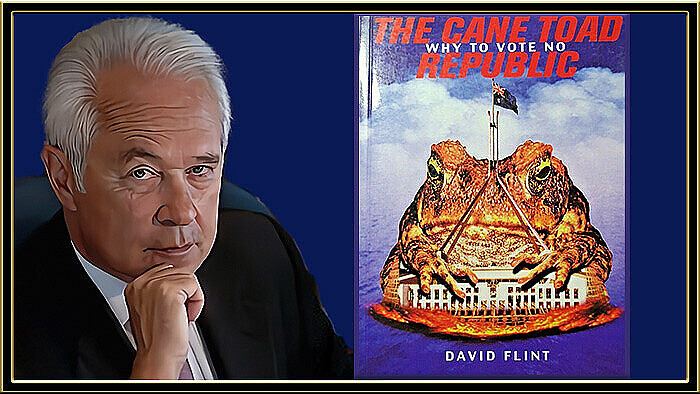

But his most cruel comment, which cut me to the quick, was that my book for the referendum campaign, The Cane Toad Republic, would end up in the remainder aisle. Imagine how I felt when I was subsequently told by a friend that the University Co-op was offering Mr Turnbull’s Fighting for the Republic at a 50% discount!

The Cane Toad Republic has given me some difficulties since it was published in 1999, but the comments I have received from readers have made these difficulties more than worthwhile. At a hearing of a Senate Estimates Committee following the referendum, every detail of my travels when campaigning during the referendum campaign was put under the microscope. Someone — I cannot imagine who would have bothered to do this after the referendum — had very carefully worked out my itinerary, mainly on the weekends or on leave.

I was asked at the beginning and the end of the questioning who had paid for my visit to Canberra for the launch of my book The Cane Toad Republic on 12 October. I first replied that I did not believe I was in Canberra that day. At the end of the interview, the Senator read a story about the book launch in The Canberra Times. “Does that refresh your memory, Professor?” Eventually, I had to point out the obvious that just because a book launch is reported in The Canberra Times doesn’t mean the book launch was in Canberra. When I pointed out that the book launch was in Sydney, the penny dropped. The questioning moved to other issues.

In the following Saturday edition of The Sydney Morning Herald, Mike Carlton said that “we” don’t have much of a brief for that cockalorum, Professor David Flint, but that I am a smooth operator. In contrast to Malcolm Turnbull’s Fighting for the Republic, no newspaper published extracts from or even reviewed The Cane Toad Republic!

My literary efforts did, however, attract some media attention. There was a press conference after the launch, which broke up in uproar because a TV reporter began chanting, over and over, and at the top of his voice, “We want section 2” (of the Constitution)!

Then there was the odd behaviour of a group of journalists, led by one from The Age. Apparently, they had received a tip that I had used the advertising power of the No Case as leverage to get an interview on Melbourne radio to promote my book! Now the proceeds of the book went to ACM (Australian Republican Movement), so there could be no personal profit for me. But the thought that I needed the leverage of the No case advertising budget just to get one talkback interview or that I would have used such leverage was preposterous. I was not a member of the government-appointed No case committee, and I had no control over that particular budget. As for the ACM, our funds were so stretched we could not even afford radio advertising in Victoria!

When the reporters learned this, it only encouraged their fantasies. They then came to the extraordinary conclusion that a substantial proportion of the official No case budget had actually been appropriated to promote my book! A lot of time and effort was thrown into trying to show this, all to no avail because it was a fantasy.

The fact is that not a cent of the $7.5 million No case funds went to the promotion of my book. And if the figures are ever published, I have no doubt that they will show how much more effectively and professionally the No case funds were spent in actually getting advertising time and space than those of the Yes case. The No case was undiluted, clear and simple; the ARM (Australian Republican Movement) spent a lot of money on a series of confusing and conflicting messages, the best being those involving former politicians. Seeing those former adversaries Malcolm Fraser and Gough Whitlam together, with Gough saying, “It’s time, Malcolm”, must have moved many uncertain voters to the No camp.