The Sixth Pillar: Federation

This is an edited version of a speech Professor Flint delivered to the Order of Australia Association. The themes here are developed in Give Us Back Our Country, How to Make the Politicians Accountable … on Every Day, of Every Month, of Every Year, by David Flint and Jai Martinkovits (Connor Court).

In addressing you as “ladies and gentlemen”, it appears I am in breach of the instructions given to schoolchildren under the Safe Schools program. This decrees that phrases such as “ladies and gentlemen” and “boys and girls” should be avoided.

In addressing you as “ladies and gentlemen”, it appears I am in breach of the instructions given to schoolchildren under the Safe Schools program. This decrees that phrases such as “ladies and gentlemen” and “boys and girls” should be avoided.

That is what is being taught or proposed to be taught to our children. Now, let us consider what is no longer being taught to our children—our heritage.

In 2006, a report about the teaching of history in Australian schools found that three-quarters of school students surveyed did not know why we celebrated Australia Day. The New South Wales Minister for Education argued that, at least in that state, the teaching of history was of the requisite standard. Asked by a radio presenter why we celebrate Australia Day, the minister replied, “Because that’s the day when it became a nation, the day the states joined together.”

Whether or not students (and a minister of the Crown) know why we celebrate Australia Day, they have been taught little about that crucial golden thread that comes to us through the Magna Carta, the Glorious Revolution, settlement and what has transpired since. Even the story of Anzac is under attack, according to Mervyn F. Bendle’s account of what he describes as “the history war on Australia’s national identity”.

The result is that our children know little about our heritage. The picture appears just as bleak in significant areas of tertiary education, where free speech is under attack, bureaucracy is dominant, and too many students are admitted to courses for which they are unprepared and which are inappropriate for their aspirations.

Yet record sums of money are being poured into education, and students are amassing substantial debt even before they work out how they will acquire the house which was once considered the birthright of all Australians. Add to that the fact that they are the generation who will pay the increasing interest on increasing government debt and will also be liable for the eventual repayment of that debt.

Australia’s youth are being denied the opportunity to know, understand and appreciate their heritage. But that is not all. This failure in educational administration is, I believe, but another example of a serious decline in the quality of the governance of this country.

Let us examine the failure to educate our children about our heritage. Young people are not being given the opportunity to understand and learn from those things which have made Australia such an exceptional nation.

Why has Australia been so successful? Are Australians racially superior? Is it our weather? Is it geographical? Or is it that we are endowed with such rich natural resources that we could never fail?

The latest research, such as that by MIT professor Daron Acemoglu, Harvard professor James A. Robinson, and Harvard and Oxford professor Niall Ferguson, concludes that not one of these factors is definitive. Otherwise, they ask, how can we explain why Botswana has become one of the fastest-growing countries in the world while other African nations are mired in poverty and violence? Or why is North Korea a failure and South Korea a success? They conclude that political and economic institutions determine economic success or failure.

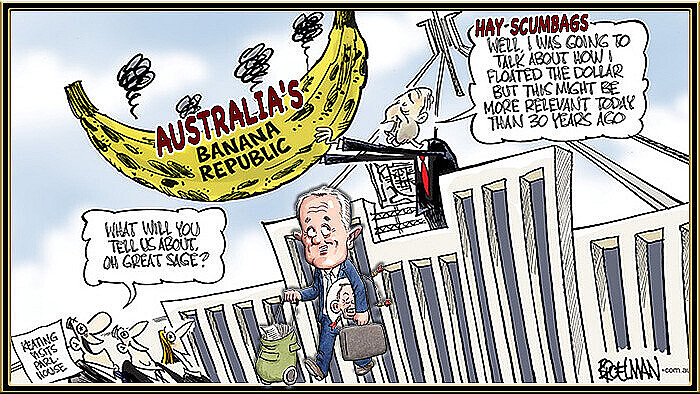

The truth of their thesis can be illustrated by recalling that at the time of our federation, Australia and Argentina were the world’s richest countries. Argentina did not then engage in the two world wars and did not suffer the enormous losses, both in terms of human potential and wealth, that Australia did. So Argentina should have been more successful than Australia. However, the twentieth-century history of Argentina was one of instability, periods of brutal dictatorship, and economic decline.

Why is this? As a former minister in Argentina’s Menem government observed on ABC’s Four Corners in 2002, there is one important difference between the two countries: “Australia has British institutions. If Argentina had such strong institutions, she would be like Australia in ten or twenty years.”

In 1788, Captain Arthur Phillip not only brought people and provisions—he brought four institutions that we have adapted, institutions that are still with us today and which, with two others, have made this nation.

The first was the English language. We were extraordinarily fortunate that this was the language not only of Britain but also of its successor as the world’s dominant power, the United States. Only those who have lived for long in a foreign country will know the enormous advantage we enjoy because we speak what is without serious challenge to the language of the world.

The second institution Phillip brought was the rule of law. This means two things. First, everyone, including and especially the executive arm of government, is subject to the law. To understand how unique this proposition is, you really have to go back to at least the Magna Carta. The second aspect of the rule of law is that while citizens may do anything not prohibited by the law, the executive government may only do those things authorised by the law.

To describe the colony as a British gulag, as one senior Australian politician has, is completely erroneous. Phillip came with a Charter of Justice, which, unlike the Soviet Constitution, was actually applied. The very first civil case in Australia can be found in the law reports, Cable v Sinclair. The Court of Civil Jurisdiction sat in Sydney on July 1, 1788, to hear this case brought by two convicts, Henry and Susannah Cable (or Kable). How they met and what brought them together is a wonderfully romantic story, one which is a great tribute to Lord Sydney as the minister responsible for establishing the colony. The case was brought against Duncan Sinclair, who was the master of Alexander, one of the ships in the First Fleet. It concerned a valuable shipment which had been sent from England. Not only did the Judge Advocate hear the case, he found the convicts and made a substantial award in their favour. That is not what happens in a gulag.

There is another aspect of the rule of law which is important. This was about slavery. Both Phillip and Lord Sydney would have been well aware of a celebrated case in 1772 concerning a runaway slave from the American colonies, James Somersett. In a case brought by his owner, Lord Mansfield is said to have concluded his judgment with the words, “The air of England is too pure for a slave to breathe; let the black go free.”

Americans, especially in the South, were appalled by this decision, which freed 15,000 slaves and left slave owners who had gone to England with their slaves without any legal recourse. Worse, they feared the precedential value of this decision in the colonial courts. The slave owners soon saw the advantages of American independence, as did those who wished to seize lands reserved to the Indians under George III’s Great Proclamation. The mantra “No taxation without representation”, in protest at taxing the colonies to help pay for the long war defending them against the French, was not the only reason for the American revolt.

Phillip was determined that the American experience should not be repeated in the new land. Before leaving England, he wrote:

The laws of this country will, of course, be introduced in [New South Wales], and there is one that I would wish to take place from the moment His Majesty’s forces take possession of the country: That there can be no slavery in free land and consequently no slaves.

As Keith Windschuttle observed in 2007, “The idea that slavery was an affront to humanity that had no place in a free land was part of the original definition of what it meant to be an Australian.”

Although Arthur Phillip’s anti-slavery declaration was well-known to earlier generations of students, historians today rarely mention it. Schoolchildren are deprived of the pride in knowing that theirs is the only continent in the world that has never known slavery.

The third institution Philip brought was constitutional government. Although Phillip had considerable powers, the penal colony was only an interim measure. It proved to be extraordinarily successful, the world’s most successful experiment in criminal rehabilitation. Phillip was not a dictator—he was subject to the law and answerable for his actions. Phillip brought with him our oldest institution, the Crown. But this was not an absolute monarchy, which was by far the dominant model in Europe, where it illustrated the maxim that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. The Crown operated under the separation of powers, which Montesquieu identified as uniquely English. Constitutional government, as Phillip knew it, was emerging as the Westminster system we know today. The king was subject to the laws, and the laws could only be changed by Parliament. It was becoming accepted that the executive government, the ministry, could only survive if it enjoyed the confidence of the House of Commons. Above all, and completely consistent with the English concept of the rule of law, people were free to do whatever was not prohibited by the law. Consequently, government, rather than being absolute, was limited to performing what was essential and in particular, defending the realm and maintaining the King’s Peace—that is, law and order.

The fourth institution which Philip brought to Australia was civil society. This consists of all of those institutions separate from government—above all, the family and the church—together with those values which are essential in a civilised society and without which neither constitutional government nor democracy can survive. The values Phillip brought can best be described as Judeo-Christian, and in particular, that version which produced the great campaign led by Wilberforce to end the institution of slavery. These values include truth, courage, love, and loving your neighbour as yourself. Even with the decline of organised religion, these Judeo-Christian values continue today to permeate our laws, our language, and our fundamental institutions. They are part of our broad Australian culture.

This does not mean Australia should not welcome those from other religions, nor does it mean that there is any obligation for an Australian to belong to any of these religions, or indeed any religion. This openness was stressed in the very first sermon preached in this land on Sunday, February 3, 1788, by the Rev. Richard Johnson. He began:

I do not address you as Churchmen or Dissenters, Roman Catholics or Protestants, as Jews or Gentiles … But I speak to you as mortals and yet immortal … The gospel … proposes a free and gracious pardon to the guilty, cleansing to the polluted, healing to the sick, happiness to the miserable and even life for the dead.

Over one century later, in the public consultations on the draft of our Constitution, more supporting petitions were received than for any other concerning a proposal that the preamble recognises what one delegate called the “invisible hand of providence”. This is reflected in the preamble of the Constitution Act, a provision which summarises, succinctly, the very pith and substance of our federation. This is that the people of each of the several states, “humbly relying on the blessing of Almighty God, have agreed to unite in one indissoluble Federal Commonwealth under the Crown … and under the Constitution hereby established”.

These institutions—the English language, the rule of law, constitutional government and civil society—Phillip brought to Australia, where they became the first four pillars of our nation. There were to be two more.

The fifth pillar of the nation was self-government under the Westminster system and within a surprisingly short period. The French, the Spanish and the Portuguese did not transmit the parliamentary concept to their colonies, as the British did to their American colonies long before independence and as they did to Australia.

Initially, the power of the colonial governor was restricted by the law and carried out under written instructions from London. This power was tempered by granting an increasing role to the people, culminating in legislation in 1850, which empowered the various colonies to draft their own constitutions, although they were still to be approved by the Colonial Office in London before being presented for the Queen’s Assent. The New South Wales and Victorian Constitutions received Royal Assent on July 16, 1855. These constitutions were not imposed by London. They were, as Professor Patrick Lane put it, “essentially home grown”.

To strike down another myth, the bills were approved in London well before the rebellion at Eureka Stockade. Whatever Eureka Stockade achieved, it was not self-government under the Westminster system.

The sixth great pillar of our nation was the Federation. This was never inevitable. We could have easily become several countries. In fact, when the British first suggested a federation, the local politicians were outraged. The assertion by former Prime Minister Paul Keating that it was imposed on Australia by the British Foreign Office is manifestly untrue. It was drafted in Australia by Australians and approved by the Australian people. When it happened, it was different from any other federation.

There were no deaths, no violence, no threats of war. Those great Founding Fathers Sir John Quick and Sir Robert Garran described this great achievement this way:

Never before have a group of self-governing, practically independent communities, without external pressure or foreign complications of any kind, deliberately chosen of their own free will to put aside their provincial jealousies and come together as one people from a simple intellectual and sentimental conviction of the folly of disunion and the advantages of nationhood.

The States of America, Switzerland, and Germany were drawn together under the shadow of war. Even the Canadian provinces were forced to unite by the neighbourhood of a great foreign power.

But the Australian Commonwealth, the fifth great Federation of the world, came into voluntary being through a deep conviction of national unity.

We may well be proud of the statesmen who constructed a Constitution which—whatever may be its faults and its shortcomings—has proved acceptable to a large majority of the people of five great communities scattered over a continent and proud of a people who, without the compulsion of war or the fear of conquest, have succeeded in agreeing upon the terms of a binding and indissoluble Social Compact.

These six pillars are the institutions which have made Australia an exceptional nation, both internally and in our role in the world. According to the International Human Development Index, our standards of health, wealth and education result in our being ranked the second nation in the world, very close to the first country, Norway. But with declining educational standards, not telling the young and the newly arrived about our heritage, and an inability to control increasing government debt, we are relying on the achievements of earlier times. How long will we stay near the top?

As to our role in the world, Australia has been involved in a remarkable way in defending the freedom and liberty of others. In the Second World War, we were one of a handful of countries that fought from the beginning to the end. As a percentage of the population, almost twice as many Australians gave their lives as Americans: 0.57 per cent to 0.32 per cent. In the First World War, more than ten times as many Australians gave their lives as Americans, 1.25 per cent to 0.11 per cent.

If we do not tell our young people about this heritage and how we have achieved it, they will not appreciate it. Worse, they may succumb to other theories, fashionable beliefs and new values which will in no way advance their welfare or that of the nation.

The mind is not a vacuum. In my view, man is programmed to believe. There is a warning about religious belief attributed to G.K. Chesterton along these lines: “When a man stops believing in God it is not that he believes in nothing. It’s that he will believe in anything.”

Putting aside religious belief, if we do not pass on to the next generation the facts about our heritage, what ideas, what propaganda will be pumped into their receptive minds?

I argued earlier that the failure in education is just one example of a broader problem concerning the quality of the governance of this country.

Unlike the situation that prevailed when I was young, university education is almost the sole responsibility of federal authorities, who now also preside over school, preschool, and vocational education. This entails a vast duplicate bureaucracy and massive financial resources, an increasing part of which is borrowed.

This is manifestly contrary to the carefully considered constitutional arrangements which the people approved and under which this country was formed. We should never forget that the federal Parliament is a parliament of limited powers set out in the Constitution. All powers not specifically granted by the Constitution to the Commonwealth are saved or reserved to the states under the Constitution.

There was a time when the people were regularly asked to give more powers to the federal Parliament. In fact, they have been asked to vote to transfer nine powers to the Commonwealth. Three of these votes have been given to the people on five occasions: monopolies, corporations, and industrial matters. All of these proposed transfers were rejected by the people.

It is an appalling fact that most of these referendums would not need to be repeated today. Through a re-interpretation of the Constitution by the High Court of Australia, they are no longer necessary. As a result, the Commonwealth enjoyed powers which the people denied it. The High Court has even said that in the interpretation of the Constitution, they cannot and will not be guided by a previous No vote in a referendum.

The late American judge Antonin Scalia was celebrated for proceeding from the commonsense view that the Constitution means what reasonable people at the time believed that it meant. He held that it was not for judges to change this original intention. If there was a need for change, this should be achieved by a constitutional amendment voted by the people. He believed any other approach, for example, that the Constitution had to be adapted to current values or that it was a “living document”, effectively meant the judges were saying that the Constitution meant what they wanted it to mean.

So, most of the constitutional barriers to vastly increasing the role and function of the federal government have been removed without the people’s consent. In the meantime, the people are constantly told by the establishment that uniformity in almost every sphere of government is overwhelmingly desirable. This is linked to a second theme: Canberra can be trusted to choose the best system to administer any sphere of government, which must be made uniform. This is invariably achieved by appointing expensive consultants who produce a report supported by vast amounts of modelling, which inevitably concludes that there is one very expensive solution to whatever problems the consultants have discovered. This solution requires a vast new Canberra-based bureaucracy to administer it.

That, of course, is not how the federation is intended to work. It is contrary to the experience and wisdom of all those who have lived under successful federal systems. It is contrary to the proposition first established by the American founding fathers that a large country can only be successful as a free democracy if the government is devolved to the lowest possible level.

We federated on the basis that the new federal entity would have limited powers, with other powers being reserved to the states. The states were to be principally dependent on their own sources of income. They would be responsible to the people of their state for the spending of that income.

The federation would thus encourage competition between the states. People would then see when one state does something well, for example, with its hospitals or its roads, and another state does it badly. People would, for example, say, “I have been to South Australia and they do this so much better than in New South Wales.”

The much-maligned former Premier of Queensland, Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen, demonstrated this. In 1977, against the strong objections of his Treasurer, he abolished death duties, a move that cost his state $30 million in revenue. As a young articled clerk, I had seen what evil tax death duties were, imposing heavy and inequitable burdens on farming and small business families, precisely when they were in no position to respond adequately. The result of Queensland’s abolition of death duties was that vast numbers of Australians from other states, especially the elderly, moved to Queensland. They voted with their feet. Within months, every other state had abolished this tax, and even Canberra followed by abolishing estate duty. We have forgotten this example of how a federation can and should work.

For some time now, Canberra has been trying to take over, at a very high cost, areas of government for which it is manifestly unsuited. Education is an egregious example. The more the Commonwealth becomes involved in education, the more standards seem to decline. The founding fathers knew this. That is why education was neither an exclusive nor even a concurrent power to be exercised by the Commonwealth. Yet the Commonwealth has been able to get away with what is a breach of the Constitution.

The founding fathers were also no doubt aware that if the Commonwealth were to undertake tasks best left to the states, it would neglect and mismanage those tasks, which were the very reasons why we federated. Take, for example, the defence of the Commonwealth, including the protection and maintenance of our borders. The acquisition of the Collins-class submarine fleet and now its replacement represents one of the most appalling and continuing failures in government administration in our history. And remember, there is no more important role for the federal government than defence. (This means the government should be concerned about the true defence of the Commonwealth and not be distracted by such peripheral issues as the provision of advice on Islamic matters to the navy and gender fluidity in the armed forces.)

We see a similar problem at the state level. This is probably the result of the states being converted into clients of the Commonwealth and forced to exercise too many of their powers under the tutelage and direction of Canberra.

Probably the most important function of any state government is protecting us against crime. There was a time when the states were effective in exercising this power. But in 2005, in the Sir Ninian Stephen Lecture, New South Wales’s prominent Crown prosecutor Margaret Cunneen said something no one else at her level would say but something which in lay terms was being repeated over and over in the lounge rooms and in the pubs of the nation: “Perhaps it is time for us to consider whether public confidence in the courts is now being eroded by the perception that the pendulum has swung rather too far in the direction of the protection of the rights of the accused person.”

There is a continuing decline in the delivery of government in this country. The solution, I believe, lies in making politicians more accountable. In the United States, we see a magnificent example of democracy in action in choosing the candidates of each of the parties for election. This operates not only at the level of the President but at every level of government. The contrast in Australia is dramatic. With exceptions, it is hard to imagine a more closed system, one which ensures candidates are chosen not so much on their merits as on their allegiance to some faceless powerbroker. In return for the cornucopia of legal, financial, and branding privileges that the parties enjoy, they should at least be required by law to be open, transparent, and democratic.

We should be looking to other countries for ways in which we can make our democracy more accountable and more responsive to the wishes of the people.

It is time for a convention to be held to consider the reform of government in this country and to make recommendations to the people. After all, that was the only way we could have achieved federation. Such a move would not involve turning our backs on the federation or pulling it down but instead building upon it.

We should not only recall those wise words of the great Irish statesman Edmund Burke, but we should also apply them:

It is with infinite caution that any man ought to venture upon pulling down an edifice which has answered in any tolerable degree for ages the common purposes of society or on building it up again without having models and patterns of approved utility before his eyes.

Society is indeed a contract … It is a partnership between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.

An understanding of the gradual development of the role of the crown, including the governor-general and the queen, requires such developments to be viewed in the context of the development of Australia as an independent nation. The developments involved changes in convention and, less often, statutes. By convention, we mean those usages or customs that are not to be found in the statute books but nevertheless are binding. In jurisdictions governed by a written constitution, there is a greater reluctance to acknowledge the role played by convention than there is where no such document exists, as in the United Kingdom.

THE AUSTRALIAN CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM

At the moment, our principal concern is directed to the conventions governing the relations between the governments of what were formerly referred to as dominions, now realms, and that of the United Kingdom and those governing the role of the governor-general. The federal constitution is concerned primarily with the division and separation of powers within Australia. It is not expressly concerned with resolving questions of nationhood or independence. A survey of Australian constitutional history reveals that Australia acquired independence by a gradual process – although the late Justice Lionel Murphy held that because Australians could change our constitution, we became independent in 1901.

A gauge by which independence may be measured is the willingness of foreign national governments to enter into treaties with Australia. Justice Barry O'Keefe reminds us that after the First World War, Australia was represented independently at the peace negotiations by Prime Minister Billy Hughes. He presses the argument that Australia was a self-governing country, not subordinate to the parliament at Westminster, but rather a partner with equality of status, not necessarily (at that time) equality of stature. That argument was accepted as a hard practical fact by the nations, including Britain, that took part in the peace negotiations. Independence was well established in the international scene by 1920.

Australian independence came to be recognised at the Imperial Conferences of Dominion, and British prime ministers convened in 1917, 1926 and 1930. According to the Balfour Declaration, the dominions were autonomous communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the crown and freely associated, as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations.

This result was explained at the 1992 conference in these words:

The rapid evolution of overseas dominions during the last fifty years has involved many complicated adjustments of old political machinery to changing conditions. The tendency towards equality of status was both right and inevitable. Geographical and other conditions made this impossible of attainment by way of federation. The only alternative was by the way of autonomy, and along this road, it has been steadily sought. Every self-governing member of the Empire is now the master of its destiny. In fact, if not always in form, it is subject to no compulsion whatever.

The Balfour Declaration recognised conventions that had already been developed. The Declaration was given statutory effect when the parliament at Westminster passed the Statute of Westminster, 1931, which recognised the full emancipation of the dominion parliaments. Now they could enact laws repugnant to the law of England (section 2), and give "extraterritorial" effect to any legislation (section 3). The statute limits the competence of the United Kingdom to legislate for the dominions to circumstances in which the relevant parliament requested and consented to such imperial legislation (section 4). The act stipulated that the operation of the dominion constitution was not affected in any way (section 7 and section 8). It also stipulated that, unlike the Canadian provinces to which it would apply, the act would not apply to the Australian states. This was at their request (section 9). Finally, the act would not have any effect in Australia until the parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia adopted the act itself by means of an adopting act (s10). In fact, the commonwealth parliament did not adopt the statute until 1942, at which time the act was given a retrospective operation "as from the commencement of the war between His Majesty the King and Germany".

The precise point at which independence was attained remains a moot point. Was it the political compact? Was it the formal offer by the mother parliament? Or was it the formal acceptance of the offer by the newly independent dominion parliament? In a fairly recent judgement, Lord Denning MR maintains independence came as a matter of evolving usage and convention rather than by means of enactment:

Hitherto I have said that in constitutional law, the crown was single and indivisible. But that law was changed in the first half of this century, not by statute, but by constitutional usage and practice. (R vs Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs ex parte Indian Association of Alberta, 1982, 2 WLR, 641, at 651)

The passage highlights the role conventions have played in the evolving relationship between governments within the British Empire and the subsequent Commonwealth of Nations. Were such relations governed by the rigidity of statute such developments could not occur so naturally as need requires. The gradual emergence of full Australian nationhood was possible precisely because of the flexibility that is offered by convention. It has been argued that legal independence did not occur until the passage of the Statute of Westminster through both imperial and dominion parliaments was complete. In a passage dealing with the difficulty of making such a determination, Chief Justice Sir Garfield Barwick said:

The historical movement of Australia to the status of a fully independent nation has been both gradual and, to a degree, imperceptible ... though the precise day of the acquisition of national independence may not be identifiable, it certainly was not the date of the inauguration of the Commonwealth in 1901. The historical, political and legal reality is that from 1901 until some period of time subsequent to the passage and adoption of the Statute of Westminster, the Commonwealth was no more than a self-governing colony though latterly having dominion status. (China Ocean Shipping Co. v South Australia, 1979, 145, CLR 172 at 183)

The position was certainly resolved by the Australia Acts of 1986, which make certain that Australia is absolutely independent of the United Kingdom. Sir Anthony Mason, then Chief Justice of Australia, held this to be the true date of a hand-over of sovereignty, explaining that the Australia Acts: "marked the end of the legal sovereignty of the imperial parliament and recognised that ultimate sovereignty resided in the Australian people". (Australian Capital Television Ltd v Commonwealth, 1992, 177, CLR 106 at 138)

With the Balfour Declaration and the Statute of Westminster had come the termination of British legislative and executive responsibility, at least for the commonwealth, if not the states. Judicial responsibility remained, however, until the termination of appeals to the privy council (Her Majesty in Council), which had become part of the Australian court structure.

There are four significant points about the Australia Acts of 1986. Firstly, the bulk of the acts is concerned with severing those remaining legal ties between the states and the United Kingdom. These gave the state legislatures the full powers that the United Kingdom had previously retained — at Australia's request — to leg¬islate for the state as well as the power to legislate extra-territorially. The Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865 and the doctrine prohibiting repugnance to the law of England no longer applied (section 6). British executive responsibility and privy council appeals from the state disappeared (section 10 and section 11).

Secondly, the Acts clarify the role of the queen and the governors regarding the states. The state premiers would give advice on the exercise of royal powers, not through the British government, but direct to the queen. The premiers were never prepared to go through Canberra.

Thirdly, the Statute of Westminster was amended in several respects. These included the termination of the power of the United Kingdom parliament to legislate for the commonwealth, the states and territories thereof, even at the request of the Australian parliaments. (Notwithstanding this, over recent years, some Republicans have made the bizarre suggestion that the British parliament should be requested to impose a republic!) Now no British Act can henceforth apply to any Australian jurisdiction (section 11 and section 12).

Fourth, the Acts stipulate that the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act and the Statute of Westminster continue to be in force and provide an intricate method by which the Australia Acts and the Statute of Westminster may be amended. Both Acts, enacted in substantially identical terms by the United Kingdom and Australian parliaments, were proclaimed by the queen to come into effect on March 3 1986. On arrival in Australia to proclaim the Australian version, she observed both the rise of an Australian national identity and the circumstances under which the constitutional relationship between Australia and the United Kingdom had come to an end:

I can see a growing sense of identity and a fierce pride in being Australian. So it is right that the Australia Acts has finally severed the last of the Constitutional links between Australia and Britain, and I was glad to play a dual role in this. My last official action as Queen of the United Kingdom before leaving London last month was to give my assent to the Australia Acts from the Westminster Parliament. My first official action on arriving in Australia yesterday was to proclaim an identical Act, but from the Australia Parliament – which I did as Queen of Australia. Surely no two independent countries could bring to an end their constitutional relationship in a more civilised way, and I hope you will agree with me that this has been symbolic of the depth and quality of the relationship between Australia and Britain. Anachronistic constitutional arrangements have disappeared – but the friendship between the two nations has been strengthened and will endure. (McDonald, 67)

What we have seen since the adoption of the Australian con¬stitution is the gradual emergence of Australia as an independent nation. This surely is one of the beauties of our system – that it has permitted such a peaceful evolution.

As Sir Harry Gibbs explains:

Our Constitution has been criticised because it sketches the outline of the system of government and does not set out in detail the rules and conventions that determine the working of the various arms of government. Any such criticism is totally misconceived. The strength of our Constitution, as it has been the strength of the Constitution of the United Kingdom, is that it allows the needs of a changing society to be met by a gradual development, which has been found impossible in some nations whose written Constitutions attempt to lay down all the rules in detail. (Gibbs, 1994)

[Read More: Australia In The Twenty-First Century: An Independent and Self-Determining Nation, by The Honourable Barry O'Keefe, AM, QC ]

The republican model, the Keating Turnbull republic, was then referred to the people.

This emerged in the last days of the Constitutional Convention. This was the Second Keating-Turnbull Republic, one which was highly authoritarian and anti-federal and which was suddenly pulled out of the hat. After telling us in 1993 that there was an almost universal view that the President was not to hold office at the whim of the Prime Minister, the ARM (Australian Republican Movement) now proposed the first republic in recorded history where it would be easier for the Prime Minister to dismiss the President than his cook! Not developed from the point of constitutional principle, this model was formulated only to procure the maximum votes from the politician delegates so as to obtain a majority vote at the Convention. And it failed even in that.

But as the constitutional model was chosen and preferred by the largest number of Republican votes at the Convention, the Prime Minister honoured an election promise and put that model to the people.

In the resulting campaign in 1999, the Yes case coalition was to come out with at least six conflicting messages.

Mr Malcolm Turnbull and Mr Greg Barns of the ARM (Australian Republican Movement) said that if you voted Yes, there would be no substantial change to the Constitution.

Mr Thomas Keneally, the author and spokesman for the ARM (Australian Republican Movement), said that if you voted Yes, the result would be the biggest structural change to the Constitution since the Federation.

Mr Andrew Robb, former Liberal Party Director and spokesman for Conservatives for an Australian Head of State said that if you voted Yes, you would escape from the horror of ever being allowed to choose the President. You would never have to elect the President, principally because you would never be allowed to do this.

Mr Kim Beazley said that if you voted Yes, he would allow you to decide — at some later time and if he became Prime Minister — whether you would wish to be allowed to elect the President.

Sir Anthony Mason and Mr Jason Li seemed extremely worried by an imagined "rule" that the Governor-General never appears with the Queen. This, they said, proved the Governor-General not to be that Head of State which the Keating Government said he was and held him out to be inferior to foreign governments. (The lack of such a "rule" was exposed by Sir David Smith when he drew attention to an official photograph of a State occasion showing the Queen sitting next to the Governor-General and with Sir Anthony in the group!)

Mr Jason Li also seemed to be promising greater sexual freedom, although whether this would be before or after the republic was installed was not clear.

Out of this cacophony, out of these contradictory acts and voices, there was only one single theme. It was to get rid of the Queen. And, clearly not understand the institution of getting rid of the Australian Crown. At any price.

Even at the price of an unwise, unprecedented, undemocratic accrual of power. Even at the price of constitutional and government instability.

Behind this Yes case was a grand coalition of unusual bedfellows:

Against that, not a lot. Only a band of men and women, almost all volunteers, whose ranks by the 6 November 1999 grew to over 50,000 Australians. Almost a parallel, single-purpose political party! Kerry Jones (2000) proved a superb leader of that campaign, with a rare command of advocacy, political, organisational and financial skills. Unlike the Australian Republican Movement, Australians for Constitutional Monarchy has only had two Executive Directors, Kerry Jones and Tony Abbott. (It has had only two National Convenors, Justice Lloyd Waddy and myself) In contrast to ACM's grassroots organisation, it was all so easy for the ARM (Australian Republican Movement). For its foot soldiers, all it had to do was ring the Secretaries of the Australian Labor Party and the ACTU.

The Results

When I saw the patently flawed Republican model adopted at the Convention, greeted by the headline "It's all over bar the voting", I had expected that the Yes vote in the referendum would have even been lower than that recorded on 6 November. We were subsequently warned that the electoral system would probably make the Yes vote larger than it actually was. First, there is no verification of recent registrations. Secondly, voting is no longer restricted to one polling place, and there is no means of preventing voting in two or, indeed, several places, especially in inner metropolitan electorates where anonymity is virtually guaranteed.

In addition, I did not expect that so many people in politics, the law, the media and elsewhere would throw themselves with such enthusiasm behind such a bad model. I had not expected that so much of the media would so unashamedly campaign for such a flawed model in news columns and broadcasts. Ted Mack, the wise man, foresaw that they would do so. He warned me at Corowa, well before the campaign, that they would do so because so many relished the centralisation and concentration of power that the model offered.

Nevertheless, we in the No case had believed all along that Australians, as Richard McGarvie puts it, are wise constitutional people. We had confidence in the people of Australia. The result was a landslide. Taking into account informal votes, and non-voters, about 43% of the electorate voted Yes. While Republican lawyers assumed that constitutional success for the Yes case required that it capture four states, all six States voted No, and the Northern Territory voted No. Only the Australian Capital Territory voted Yes. (A better view, held by former Chief Justice Sir Harry Gibbs and Richard McGarvie, was that the change was so fundamental all six original states needed to agree.)

Every regional electorate voted No. Every rural electorate voted No. Every truly outer suburban electorate voted No. Seventy-two per cent, 72% of all electorates voted No. In South Australia, 75% of electorates voted No. In Tasmania, 80%, and in Western Australia and Queensland, 93%!

When I was interviewed on the Sydney Opera House balcony by the BBC early in the evening of 6 November, above the marquees displayed below to welcome Republicans celebrating their victory, I said that it already looked like a landslide. Young Republican Jason Li, who was also being interviewed, looked at me in utter amazement.

The campaigning and its consequences — some personal experiences - By David Flint

After the referendum, Malcolm Turnbull (2000) published his referen¬dum diary Fighting for a Republic (which Julian Leeser said should be renamed Whingeing for the Republic). In it, Turnbull has some harsh words to say about me. Not only am I lacking in humour and a carica¬ture of a monarchist — I also have a "pseudo-British" or a "pseudo-English" accent. I am extreme, untruthful, raising one scare after another. I am not at all a constitutional lawyer (although I have taught and published in the area). Then, on 2 November 1999, Turnbull condoned a very personal attack on me by his campaign director Greg Barns who, he wrote, was clearly in an "if you see a head, kick it" mode. Turnbull justified this because campaigning rationally and courteously had not done the ARM (Australian Republican Movement) much good!

But his most cruel comment, which cut me to the quick, was that my book for the referendum campaign, The Cane Toad Republic, would end up in the remainder aisle. Imagine how I felt when I was subsequently told by a friend that the University Co-op was offering Mr Turnbull's Fighting for the Republic at a 50% discount!

The Cane Toad Republic has given me some difficulties since it was published in 1999, but the comments I have received from readers have made these difficulties more than worthwhile. At a hearing of a Senate Estimates Committee following the referendum, every detail of my travels when campaigning during the referendum campaign was put under the microscope. Someone — I cannot imagine who would have bothered to do this after the referendum — had very carefully worked out my itinerary, mainly on the weekends or on leave.

I was asked at the beginning and the end of the questioning who had paid for my visit to Canberra for the launch of my book The Cane Toad Republic on 12 October. I first replied that I did not believe I was in Canberra that day. At the end of the interview, the Senator read a story about the book launch in The Canberra Times. "Does that refresh your memory, Professor?" Eventually, I had to point out the obvious that just because a book launch is reported in The Canberra Times doesn't mean the book launch was in Canberra. When I pointed out that the book launch was in Sydney, the penny dropped. The questioning moved to other issues.

In the following Saturday edition of The Sydney Morning Herald, Mike Carlton said that "we" don't have much of a brief for that cockalorum, Professor David Flint, but that I am a smooth operator. In contrast to Malcolm Turnbull's Fighting for the Republic, no newspaper published extracts from or even reviewed The Cane Toad Republic!

My literary efforts did, however, attract some media attention. There was a press conference after the launch, which broke up in uproar because a TV reporter began chanting, over and over, and at the top of his voice, "We want section 2" (of the Constitution)!

Then there was the odd behaviour of a group of journalists, led by one from The Age. Apparently, they had received a tip that I had used the advertising power of the No Case as leverage to get an interview on Melbourne radio to promote my book! Now the proceeds of the book went to ACM (Australian Republican Movement), so there could be no personal profit for me. But the thought that I needed the leverage of the No case advertising budget just to get one talkback interview or that I would have used such leverage was preposterous. I was not a member of the government-appointed No case committee, and I had no control over that particular budget. As for the ACM, our funds were so stretched we could not even afford radio advertising in Victoria!

When the reporters learned this, it only encouraged their fantasies. They then came to the extraordinary conclusion that a substantial proportion of the official No case budget had actually been appropriated to promote my book! A lot of time and effort was thrown into trying to show this, all to no avail because it was a fantasy.

The fact is that not a cent of the $7.5 million No case funds went to the promotion of my book. And if the figures are ever published, I have no doubt that they will show how much more effectively and professionally the No case funds were spent in actually getting advertising time and space than those of the Yes case. The No case was undiluted, clear and simple; the ARM (Australian Republican Movement) spent a lot of money on a series of confusing and conflicting messages, the best being those involving former politicians. Seeing those former adversaries Malcolm Fraser and Gough Whitlam together, with Gough saying, "It's time, Malcolm", must have moved many uncertain voters to the No camp.

The Federation of Australia was a Unique Achievement:

- Although the British had first proposed it decades before, it was actually drafted in Australia by Australians and approved by the Australian people in each of the colonies states.

- The British allowed Australians to change their Constitution without reference to London.

- The Governor-General was Granted by a constitutional provision the direct exercise of the executive power of the Commonwealth.

- It was Peaceful.

Federation was thus the sixth pillar of the nation.

Australia has been able to enjoy a peaceful, limited government, both in times of peace and war, as well as during times of prosperity and depression, thanks to the Federal Constitution. This document has allowed the nation to transition from being a self-governing Dominion within the British Empire to achieving full independence as a Realm within the Commonwealth. The Federation was established on the principle of the new entity being an indissoluble Federal Commonwealth under the Crown, which remains a fundamental aspect of the nation's federal structure. While there have always been individuals who sought to remove the Crown, these individuals were not elected to the nineteenth-century conventions.

For almost all of the first century of the federation, no Australian leader had questioned the place of the Crown in our constitutional system.

In 1993, the Australian government, led by Prime Minister Paul Keating, initiated efforts to explore the potential for Australia to transition to a republic. A Republic Advisory Committee, helmed and chaired by Malcolm Turnbull, was established to conduct the necessary research.

The committee mandated that all appointees must demonstrate a prior commitment to removing the Australian Crown, regardless of any advice sought from the Premiers regarding appointments.

This report presents insightful research regarding Republican models. Back in 1995, the prime minister expressed the government's intention to pursue a proposal to modify the Constitution by eliminating the monarchy. Under the new system, the president would be selected through an election and can be removed through a two-thirds majority vote during a joint session of the Senate and House of Representatives.

The proposal did not move forward due to the defeat of the Keating government in the 1996 election.

In 1997, in pursuit of an election promise, the Howard government called an election for half of the places to the Constitutional Convention, which met in 1998.

The remaining members were appointed and were mainly ex officio. By their voting at the Convention, it was clear that a majority of the appointed members favoured removing the Crown.

Although the Convention voted for change, the model preferred by the overwhelming majority of Republican delegates could not command a majority vote. To the approval of the Republican movement and most of the mainline media who were campaigning for change, the Prime Minister ruled that this would be the subject of a referendum.

In 1999, a referendum was called in which the people were invited to vote on this republican model. This was the referendum model, which had the overwhelming support of the Republican delegates to the Constitutional Convention. Most of the mainline media and most of the sitting politicians campaigned in its favour.

The referendum was defeated nationally (55:45), in all states and 72% of electorates. After the defeat, the ARM and the Labor Party called for a national plebiscite to be held in which people would be asked whether they wanted Australia to become a republic. No details would be revealed.

If this were passed, another plebiscite would follow in choosing between different forms of republics. The existing constitution would be excluded from that vote. After the second plebiscite, a referendum on the preferred Republican model would follow. After this, a conference was held at Corowa, which endorsed this plan.

A Senate Inquiry was established in 2003, which produced a report just before the 2004 election, Road to a Republic. This endorsed the ARM-ALP proposal for two plebiscites, but Liberal Senator Marise Payne, an ARM office bearer, dissented from the proposal for two plebiscites.

Then came a Republican “Mate for a Head of State” campaign, which failed to create any support for a renewed campaign, and then the 2020 Summit, whose governance panel, after minimal discussion, voted an improbable 98:1 in favour of Australia becoming some vague, undefined republic.

Shortly after the Summit, the Morgan Poll reported the lowest support for a republic in 15 years, with very low support among the young.

In 1993 Prime Minister Paul Keating established a Republic Advisory Committee (RAC) to advise him on the various options for minimal change necessary to bring about a republican government in Australia. The RAC's terms of reference stipulated that it should not address any broader issues regarding other areas of constitutional reform or the normative question of whether Australia ought to become a republic. It should also not make any final recommendations but rather address the advantages and disadvantages of the possible approaches to a specified list of matters. (RAC, Vol. 1, p iv)

So the Republic Advisory Committee was not intended to debate the advantages or disadvantages of a republic over the existing system. Its formation reflected Keating's adversarial style. He once argued that the first question about a republic was: "Do you support an Australian republic?" Only if you supported such an entity were you to be admitted to the forum that would discuss the form of the republic. This theme was brutally applied both in terms of reference and of the membership — totally Republican — of the RAC. It was chaired by Malcolm Turnbull, the leader of the Australian Republican Movement.

When the prime minister gave his response to the report, he endorsed the desirability of Australia becoming a republic on the basis of a "minimal" change to the constitution. He addressed five areas of change. The principle components involved:

It was Keating's stated intention that the transition to a republic would be a small step, albeit a highly significant one, with minimal disruption to the system by which Australia is governed. There was dissent in the Republican ranks, however, as to just how small the step being proposed was. One democratic-republican, the late Professor Patrick O'Brien, explained:

In his speech, Keating repeated the false claim that the move from a constitutional monarchy to a republic was a small step. It is a giant leap. In itself, the institution of a republic means the institution of a new constitution and a new political order. Whether it is a giant leap forward or backwards, therefore, depends upon the constitutional distribution, weighing and checking and balancing of power and authority among the people, the parliament, the executive, the bureaucracy and the High Court. (O'Brien, 158)

It was quite clear that Professor O'Brien saw the Keating–Turnbull model as a giant leap backwards.

After Prime Minister Keating’s response to the report of the Republican Advisory Committee, a model for the Australian Republic emerged, the first Keating -Turnbull republic.

APPOINTING THE PRESIDENT

The first Keating–Turnbull model has met with both practical and ideological criticism. Despite strong electoral support for popular elections, the Keating government advocated parliamentary appointment and dismissal. Clerk of the Senate Harry Evans has argued against this method of appointment on principle:

Most people, not intellectuals, are able to detect the massive contradiction at the heart of the elite orthodoxy: the monarchy must go partly because it is undemocratic, but the people must not be allowed to choose the replacement because they would stupidly make the wrong choice. (News Weekly, 29 July 1997)

Bill Hayden, a former governor-general, warns of the practical effect of election by the special parliamentary majority:

Those who believe a president elected by both Houses of Parliament would attract nominations from the 'best people in the community', need to be reminded of the adversarial structure of our political system. The hectoring style of so many Senate Committee hearings is illustrative of the sort of grinding and very personal inquisition to which a nominee could be subjected. The process here would make the Supreme Court confirmation hearings of the USA Senate, such as in the cases of Dinks and Hill, look like a suburban manse morning tea party. The prospect of such an experience would discourage all but the stout-hearted. (Hayden, 548-549)

The election of the president would be by a joint sitting of both houses of the federal parliament. So the greatest say would be to the most populous states, effectively the Canberra, Sydney, and Melbourne axis. A two-thirds majority would be required. It would be a strange election, at least outside of the totali¬tarian countries. There would only be one candidate, just as in the old Soviet Union. The thinking was that at least the government and opposition would have had to support the candidate. This is not guaranteed. The Fraser government came down to having a two-thirds majority. A change by legislation of the method of election of the Senate could easily increase the likelihood of governments commanding this majority. This does not need a constitutional amendment. It can be done by legislation.

In the meantime, the attempt to force an agreement between the government and the opposition assumes that both will act in the best interests of the nation and choose the best candidate. What will obviously happen is a deal. In return for support for a candidate, the other side will agree to support some measure or not take some action – secretly, of course.

Australians have already seen and are disenchanted by this wheeling and dealing. The American founders saw the danger of deals between politicians and with the candidate, both in election and re-election. So, they decided to remove the politicians from the presidential election process.

THE CANE TOAD REPUBLIC

And even a single candidate election is still an election. As minister Bronwyn Bishop says, in an election, the candidate has to stand for something – his or her platform. By winning, he or she has a mandate. This is totally unlike the non-political governor-general who has neither a platform nor a mandate. So what do we have under this republic? A politician chosen by politicians. And with an enormous mandate – two-thirds of parliament. The prime minister, by contrast, may have a little over half the house and a minority in the Senate. Who would have the biggest mandate?

DISMISSING THE PRESIDENT

Perhaps the most serious problem with the first Keating–Turnbull republic was that raised by one with first-hand experience of viceregal office, Richard McGarvie, who warned against the threat to democracy that would result from instituting a head of state who was not readily dismissible:

The fatal flaw of the models many Republicans still support is that a president elected by parliament or the people could not be promptly dismissed. That sanction for breach, which gives binding effect to the convention of exercising the great powers of the head of state as elected ministers advise, would disappear. Oppositions do not support governments. No federal government for fifty years has had that majority. Even if it did, a president could stymie dismissal by exercising the power to dissolve or adjourn (prorogue) parliament. Our democracy depends on the sanction of dismissal and if it evaporates so will democracy. (Adelaide Review, December 1997)

Professor Flint argued for ACM that without codification, this proposal would import into Australia something like the French Fifth Republic, where a powerful president "cohabits" uneasily with a parliamentary prime minister. The French have such a system only because their efforts to have a US-style republic or the Westminster system failed. The ARM's reaction to this and other ACM criticisms was to denounce our arguments as scare-mongering.

CODIFICATION OF THE RESERVE POWERS

The basis of the new presidency under the Keating government's model was that the new head of state would simply "slip in" to the role presently carried out by the governor-general. Republican Professor Patrick O'Brien argues that the governor-generalship cannot be stripped of its monarchical overtones:

Abolish the crown, and you thereby also abolish the office of governor-general. Its political and metaphysical functions cannot simply be transferred to another office, regardless of what it is called. These powers are inseparable from the crown. The fashioners of the United States Constitution understood this simple point. Hence, the creation of the brand new executive offices followed two decades of the most intense, polemical debate about the future constitutional shape of their proposed republic. (O'Brien, 159-160)

The staunchest of Republicans and the staunchest of monar¬chists find themselves bedfellows in their common opposition to the Keating government's attempt to graft a republican institution onto our monarchical constitution. As Professor Lane observed, rather than attempting to graft a republic onto a monarchical constitution, republicans should develop a new constitution. Justice Lloyd Waddy, as Convenor of ACM, wrote that the way to achieve a republic is a radical rewrite of the constitution as the Americans did, not merely preserving the present arrangements but severing them from their source of legitimacy:

When I begin most speeches on republicanism, I make two basic state¬ments. First, I say, Of course, we can have a republic if a sufficient majority votes for it. If the Americans can run a republic for two hundred years with only one (very bloody) civil war, Australians could run two republics before breakfast. Secondly, I add, if you want me to nominate a republican system I would presently favour, it is that of the USA; we know it is safe and that it works in its way, and it has done so for over two hundred years. But I must confess that I believe the operation of its system of government, with an executive-style presidency, is infinitely inferior to our own. (Grainger and Jones, 101)

THE CANE TOAD REPUBLIC

One of the greatest sticking points of Prime Minister Keating's speech responding to the RAC's report, however, was his preferred treatment of the reserve powers of the crown – the powers which do not require the advice of the ministers of the crown. Under the first Keating–Turnbull republic, the reserve powers of the governor-general would continue to be exercisable by the president, but they would remain uncodified. Rather, a provision would be inserted into the constitution, providing that the informal conventions governing the operation of the vice-regal reserve powers – whatever they may be – would continue to operate to bind the new head of state.

The failure to codify the circumstances in which the reserve powers could be exercised was deemed catastrophic by some Republicans. Writer Donald Horne explained shortly after the Keating proposal was announced:

Since a president would be harder to get rid of than a governor-general, it is prudent for us to change our Constitution to say what powers a president has and, therefore, by inference, what powers a president does not have ... after a referendum, we would insert into the Constitution a section saying that, except in specified circumstances, the president would act only on the advice of the government. (Sydney Morning Herald, 27 October 1995)

He said: "Without a clear statement of the president's powers, even I will vote No in a referendum." (Sydney Morning Herald, 3 June 1995)

Malcolm Turnbull similarly favoured codification, although he supported Keating's method of appointment. He has emphatically declared that: "I support full codification of the powers of the president." (Turnbull, 166)

The ARM Platform adopted a similar stance: "The functions of the president shall be spelt out in the Constitution." There appear to have been two grounds for arguing against codification. One revolves around the difficulty of the exercise. As Senator Gareth Evans explained, the "definition [of the present controversial unwritten conventions would be] a labour of Hercules. Reformers would have to devote thirty years to the task to have an impact ... Frankly, I think the task is impossible." (Australian Financial Review, 9 May, 1995) In other words, the problem of codification already exists in the present arrangements and concentration on the problem will only hinder progress towards a republic. Professor O'Brien argues that however desirable and effective non-codification has been, it is a creature of historical developments that will necessarily disappear.

The removal of the crown, he says, "will also mean the removal of these royal prerogatives and reserve powers, whatever they are". He asks in whose name will the powers be exercised —the prime minister's, the parliament's, the high court's, or the people's? What will be the source of those powers? How are they to be defined, and in relation to what? What will be the due processes governing the office and its relationship with other major institutions of government? Surely, he writes, these and numerous other questions must be answered to the satisfaction of the people and be codified. And if these powers are not con¬ferred upon the president by a majority of the people at a free election, the president would be deprived of the respect of the people. The incumbent will correctly be perceived as the parliament's and the executive's poodle.

It appears that the proponents of this republic have thrown up their hands in despair. They say that codifying the reserve powers is far too difficult. But if Australia is to become a republic, surely you have to set out the powers of each of the offices of the republic. The crown has been removed, and these conventions depended on the crown for their lives. Some might say that it is more a matter of luck than design that Australia's constitutional arrangements are as they are. But is that not the very advantage of evolution over revolution? Were it not for particular historical developments, we might not have the flexible arrangements we enjoy now. A republic will and must change the existing structures. This was played down by the Keating government to make the product appear more marketable. Yet without the crown, we have an inherently unstable mixture.

On the one side, we have those, such as Dr John Hirst, the his¬torian who still wants the flexibility of uncodified powers to be carried into the Keating–Turnbull republic. On the other side are Horne and O'Brien and the warning that codification is necessary if a new institution is to be established. The crisis is between the desirability of flexible arrangements and the knowledge that a new order must provide all its own rules, not rely on the conventions of the one it supersedes. It is clear that Republicans cannot have it both ways.

The Keating–Turnbull model expects that the new president would represent Australia overseas and be the embodiment of Australian identity.

High Court Justice Michael Kirby, for instance, rejects the suggestion that the president should, of necessity, represent the nation's interests overseas in a way the queen does:

To the complaint that the Queen is not seen as a representative of Australia when overseas, a ready answer may be given: the Prime Minister should be the main representative of Australia overseas. We can survive the shame of a nineteen-gun salute. Our system is Parliamentary. That means a Prime Minister. Let him or her be Australia's representative overseas. And in the unlikely event that the people of Asia, or anywhere else, care the slightest about our constitutional arrangements, let them mind their own business. Just as we mind ours in relation to their constitutions. Such things are the product of history and sentiment and are not always susceptible to easy explication to neighbours.

And when it is lamented that the queen never represents us overseas as Queen of Australia, a further answer is obvious. Her Australian ministers have never advised her to do this. In fact, the governor-general has occasionally represented us, but more frequently, it has been the role of the prime minister and the ministers. The other key role of Keating's president is to be the embodiment of the Australian national identity. Chancellor of the University of Sydney Dame Leonie Kramer explained in a speech at the ACM launch on 4 June 1993 that there can be no one exhaustive expression of such an identity:

As for the question of identity, suffice it to say that there is no reason why individual Australians should subscribe to some common notion of what it is to be Australian. There is room for all the differences of opinion that a mixed society such as ours can contain ... what does matter is that we share common values relating to democratic policies and practices, representative government, a non-political legal system, private enterprise, educational systems committed to high standards in teaching and learning, equality of opportunity, and tolerance of others' views – in short, a free society. The best guarantee of the maintenance of these values is our indigenous form of constitutional monarchy.

In fact, to most Australians, the national identity is about respect for democracy, the rule of law, tolerance, English as the national language and freedom of expression. For the small elite, a new presidency may seem to be a strong assertion of Australian identity and independence. But this is not at all true of the rank and file. As Geoffrey Horne said at the 1998 Constitutional Convention:

Becoming more competitive in trade with our Asian neighbours ... would assert our freedom and independence more. Having the Wallabies beat the All Blacks or the Socceroos reach the World Cup finals would more effectively assert our independence as a nation, and fixing unem¬ployment and domestic matters would have more effect in asserting ourselves as free people in an independent nation. (Report of the Constitutional Convention, 2-13 February 1998, Vol III)

THE STATES

Our final problem before leaving the first Keating—Turnbull republic is its treatment of the states. The states were to be involved in two ways. The first is that each state forms its own constitutional monarchy distinct from each other and the commonwealth. If only the part of the constitutional monarchy at the federal level is abolished, the question arises as to whether this would have any impact on the continuity of the six-state monarchies. If not, ought the states be forced to change their constitutional arrangements? Secondly, the question arises as to what role, if any, the states might have to play in the changes required to bring about a republic at the federal level, even if no change were to occur at the state level.

It was the view of the prime minister that there would be no necessary implications for the states were the commonwealth alone to become a republic, and the government had no intention of exerting any pressure on the states to make their arrangements consonant with those of a new republican commonwealth:

It is not our intention that the government's proposals should affect the Constitutions of the Australian states. It would be up to each state to decide how they would appoint their respective heads of state in the future. It is reasonable to expect that if the Australian people opt for an Australian head of state, the states would follow suit. But the question would be for each state to decide.

In this way, the difficulty of forcing the states to change was avoided, and an ordinary section 128 referendum would be suffi¬cient to establish a federal republic requiring a national majority and a majority in only four rather than all six states. However, there are good arguments that, this being a fundamental issue, the consent of the six states is necessary.

Should such a referendum be carried with only four states' support, it is conceivable that the legislation might be contested by one of the other two states on the basis that there is only one crown in Australia (albeit with seven manifestations). The destruction of that crown, it might be argued, would go to the heart of the original compact, thus constituting a renegotiation of the terms of the initial "indissoluble" compact to establish an indissoluble federal commonwealth under the crown. Furthermore, if the crown is one with various manifestations rather than seven separate crowns, destruction of it might constitute an action by the commonwealth disabling a state to operate in a fundamental sense.

Support for such a conception of the crown is to be found in Justice Rich's approach in Minister for Works (WA) vs Gulson (1944), 69 CLR 338 at 356, where he explains:

It is by the crown that all legislative and administrative authority is exercised throughout the Empire, although in each constitutional area, such authority can be exercised by the crown only through the agencies of the appropriate Parliament and the appropriate group of constitutional ministers so that legalistically, it would be more strictly accurate to speak of the state of Western Australia in right of the crown than of the crown in right of the state of Western Australia.

It is clear that the single indivisible imperial crown under which Australia federated had become several crowns, but only down to an Australian, a Canadian, or a New Zealand crown. The crown in Australia is one and indivisible. If it were the seven crowns that the RAC suggests, the indissoluble federal common¬wealth established in 1901 would be effectively dissolved. Each state could go its own way. This is a devastating result unless you try to overcome this by constitutional amendments dividing the Australian crown seven ways and abolishing one of them.

These questions could require further determination by the high court, and the first Keating—Turnbull republic was criticised by both monarchists and republicans on these grounds. For five years, the ARM insisted on the rectitude of this model. They scoffed at any criticism. And then, in the last days of the Constitutional Convention, without any adequate explanation, they changed the model to prove that the Australian president, unlike any other in the world, would hold office at the whim of the prime minister.

Also, See the Second Referendum Model

Australia's republicans rapturously applauded John Howard in 1998.

This was when he decided that the model preferred by the overwhelming majority of republican delegates at the 1998 Constitutional Convention should be put to the people.

But when this was defeated in a landslide vote nationally, in all states and 72% of electorates, the republicans blamed John Howard for their loss. Their leader Malcolm Turnbull said that if he were remembered for anything it would be as "the man who broke the heart of the nation."

John Howard was blamed for the form of the question, although this was agreed by Parliament where republicans dominated.

Since1999, the republicans have refused to reveal what changes they are proposing to the Constitution and the Australian Flag.

JOHN HOWARD - Part 1 of 10: WHY WE HELD THE 1999 REPUBLIC REFERENDUM

In this interview with the 25th Australian Prime Minister, the Hon John Howard OM explains why he called the 1998 Constitutional Convention. In summary, he believed that the question whether Australia should become a republic should be tested. If the Convention developed a model for a referendum, that should be put to the people for decision in accordance with the Constitution.

The interview, conducted by Professor David Flint, was made in the lead-up to the 20th anniversary of the 1999 republic referendum.

A report by BBC correspondent Michael Peschardt for the BBC's Newsnight in 1997 on Australians voting for a constitutional convention which would consider the future of the Queen as Australia's Head of State. In 1999 there was a referendum on whether Australia should become a republic with a Head of State appointed by a two thirds majority of parliament. There was also a vote at the referendum on introducing a preamble to the constitution. Both were defeated. In this report Michael Peschardt interviews Monarchists and Republicans in this report including furture prime minister Malcolm Turnbull and former Chief Justices Sir Harry Gibbs and Sir Anthony Mason. #MichaelPeschardt #BBC #Newsnight #AustralianConstitutionalConvention #MalcolmTurnbull

FIRST QLD ABORIGINAL LIBERAL SENATOR NEVILLE BONNER AO

Neville Bonner's Speech at the 1998 Constitutional Convention.

Neville Bonner delivers the only speech that received a standing ovation at the 1998 Constitutional Convention.

______________________________________________________

Australians for Constitutional Monarchy / No Republic!

ACM is Australia's leading Constitutional Monarchist organisation.

We exist to preserve, protect and defend our heritage: the Australian constitutional system, the role of the Crown in it and our Flag.

Sign up free by clicking on the Link Below.

Website: https://norepublic.com.au

Website: https://www.crownedrepublic.com.au

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/acmnorepublic

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/user/MonarchyAustraliaTV

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@aussiecrowntv

Twitter: https://twitter.com/acmnorepublic

E-mail: https://norepublic.com.au/contact-us

Phone 1800 687 276

Speaking at the Diamond Jubilee National Conference, Julian Leeser, the youngest delegate to the 1998 constitutional convention, reflected on the referendum campaign.

Mr. Leeser also shares several lessons which may be applicable in the future.

Professor Godfrey Tanner speaks on the Constitutional Convention relating to Australian Republic Friday 7th October 1997. Filmed by Anthony Brennan in Professor Tanner's library on Newcastle Hill (The Bestiary). More info: http://godfreytanner.wordpress.com/