Head of the Commonwealth of Nations

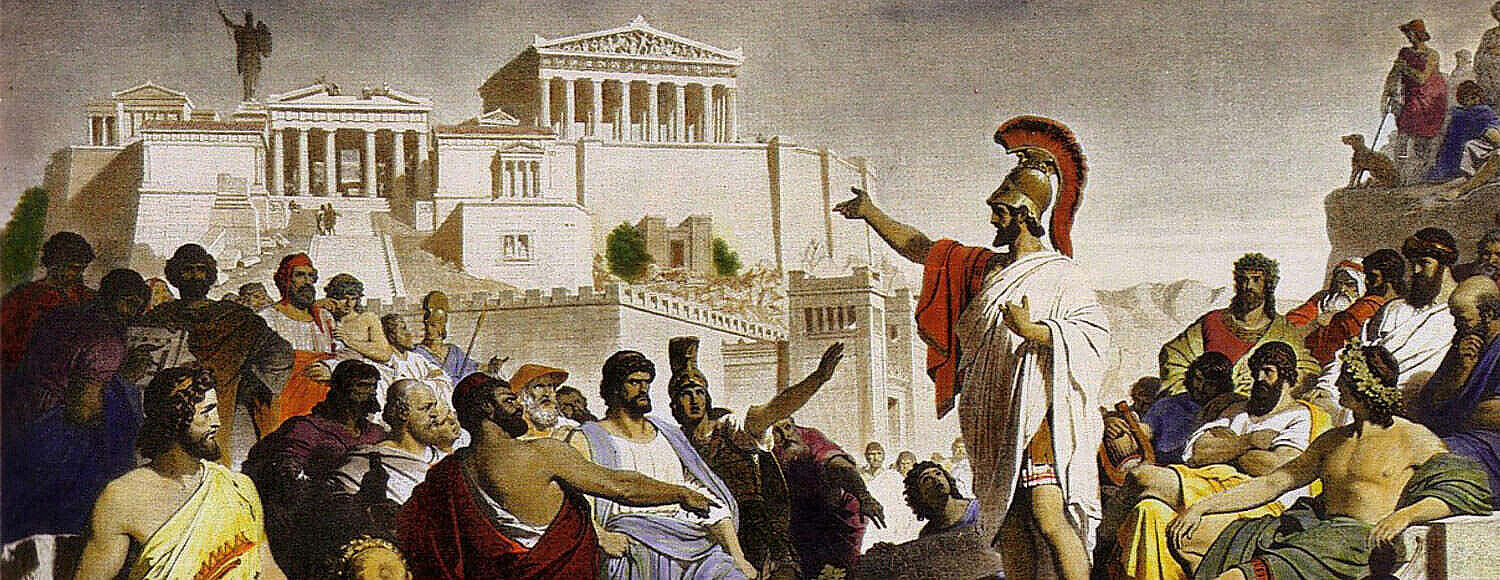

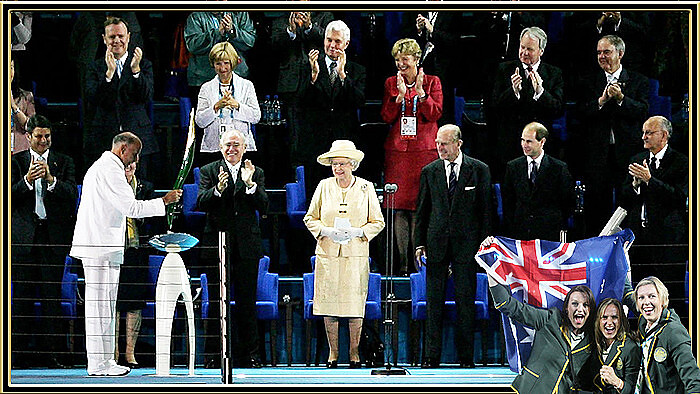

The King or Queen, our sovereign, is the Head of the Commonwealth of Nations. No one has put her contribution to this role more clearly than the thirteen-year-old Australian youth ambassador, Harry White, at the 2006 Melbourne Commonwealth Games opening. He said: “Your Majesty, during the past 54 years of your reign, you have been the glue that has held us all together in the great Commonwealth of Nations in good times and bad times. The love and great affection that we all hold for you is spread across one-third of the world's population in our Commonwealth.”

The Commonwealth is one international organisation which maintains minimum standards for continuing membership. While Zimbabwe remains suspended from the Commonwealth (it claims to have withdrawn), a glance at the membership and chairmanship of the defunct UN Human Rights Commission will indicate that different standards apply there.

The Commonwealth brings together countries that are close legally, politically, linguistically and in sport and accept certain minimum standards of democratic governance and respect for human rights. Although occasionally disparaged in the media, Australia would be most unwise not to seek to play a significant role there.

The Commonwealth indeed encompasses both constitutional monarchies and republics. But if there were to be another referendum, let us hope that the minister responsible first understands the process whereby a member changing from a realm to a republic seeks to remain in the organisation but also ensures that there would be no objection from the other members, any one of which has an effective veto in the event of change.

Self Government

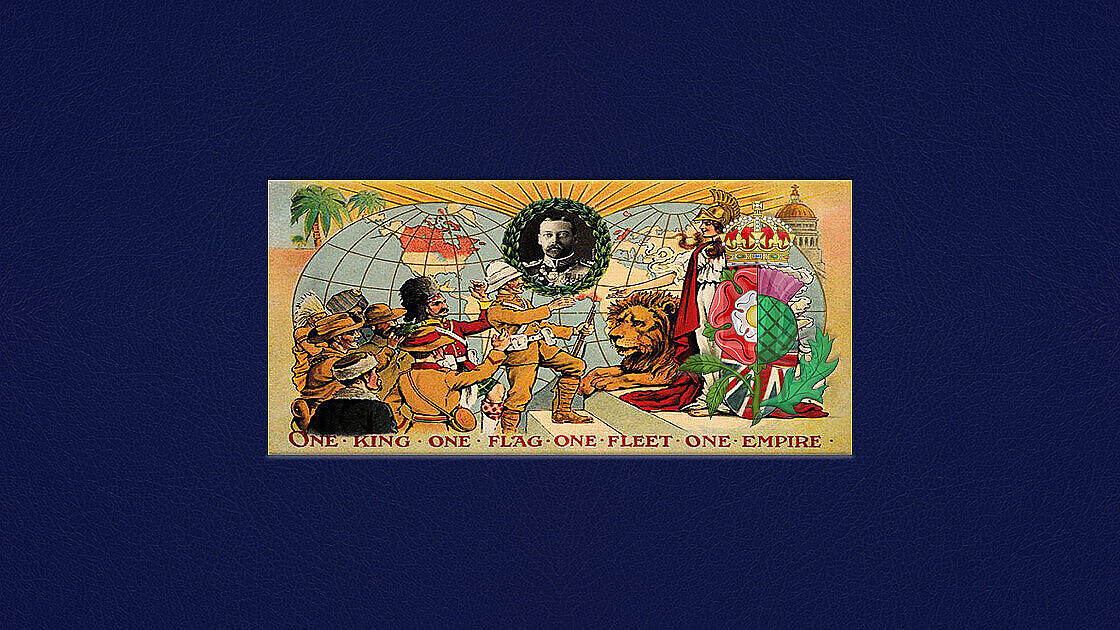

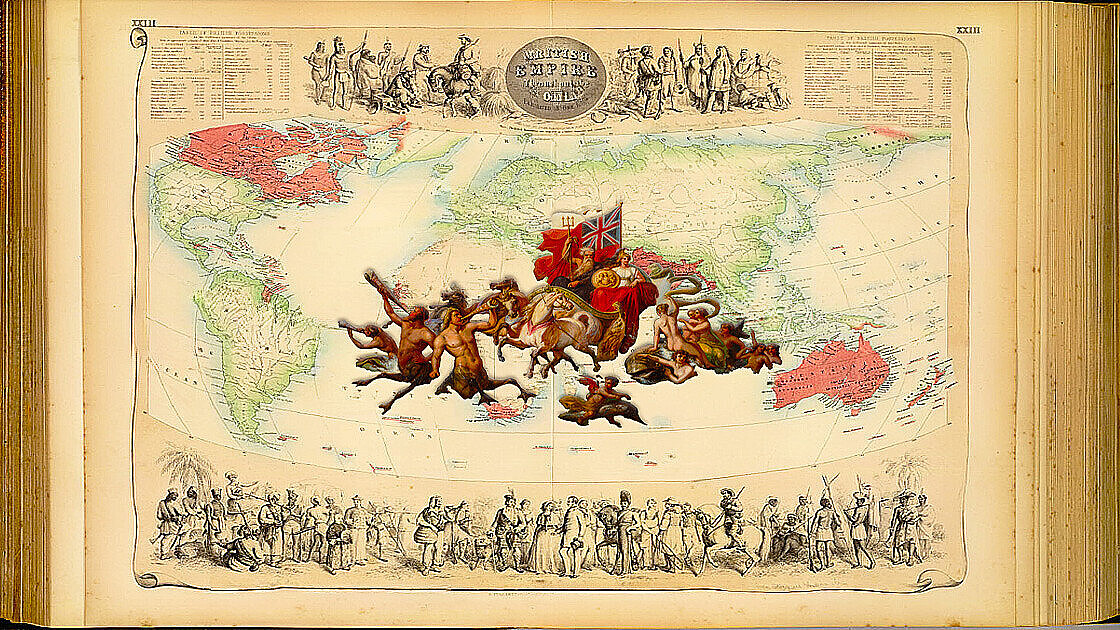

The transition of the British Empire into the British Commonwealth and then the Commonwealth of Nations was one of the most remarkable developments of the twentieth century. Before or since no other empire has so often voluntarily handed over the reins of government to its colonies. There was an attempt in the 1980s to create a similar organisation between the republics of the former Soviet Union.

The word "commonwealth" was even used. The attempt failed. The British had learned from those mistakes, which had led to the war of independence with the United States. Yet even before independence, the British colonies in America were the most free and the most autonomous that the world had yet seen. They had their own legislatures, and at times, some of the governors had been chosen locally.

The British attempt to impose taxation to recoup the cost of defending the colonies from France was only one of the reasons for the War of Independence. In retrospect, they should have obtained the consent of the colonies to that tax.

But two other key factors behind are today overlooked. One was the ruling by the influential British judge Lord Mansfield in Somerset’s Case in 1762 that a slave owner’s rights could not at common law be enforced in Britain. It would only be a matter of time before American courts would have been called to follow this ruling. What particularly upset the slaveowners was that the British government refused to introduce legislation to reverse the ruling.

The other was the Great Proclamation by King George III to restrict the thirteen colonies to their boundaries and to reserve the land to the West to the Indians.

It is sometimes forgotten today that by the nineteenth century, Britain enjoyed responsible government, liberal institutions and the rule of law, as well as considerable personal freedom. ( Responsible governments answer to and must have the confidence of the lower house of parliament.)

Vernon Bogdanor observes that these elements were readily transferred to the settler colonies in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and parts of South Africa. The mainland European empires did not and could not do this. Why? Because most did not enjoy such benefits in their home countries.

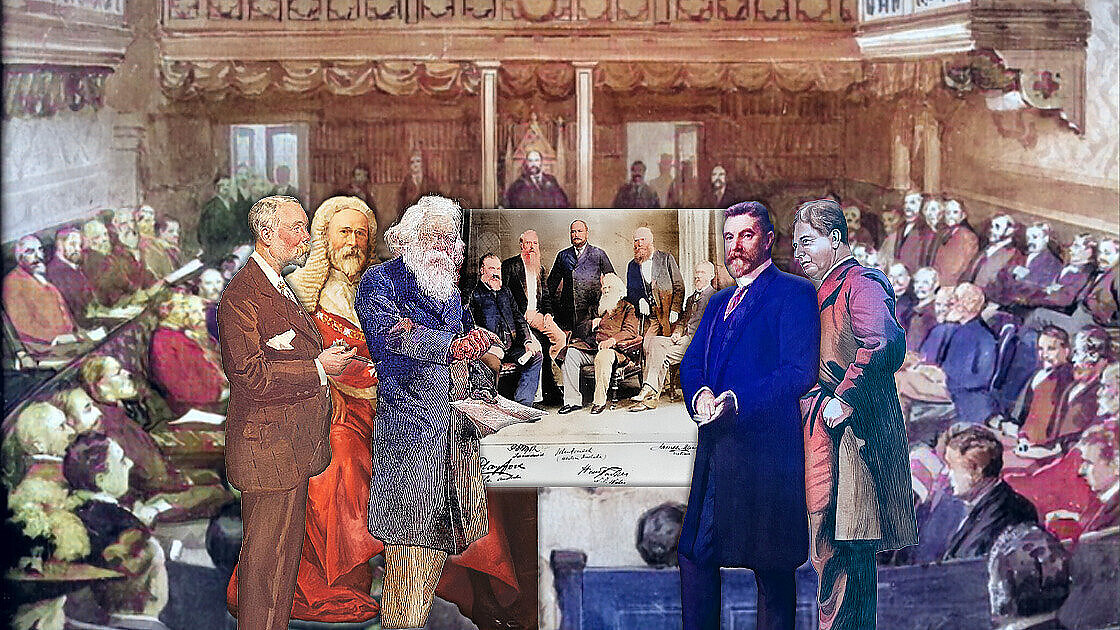

The great impetus for decolonisation was the Durham Report of 1839. Recognising that the Canadian provinces already had their own representative legislatures, Lord Durham proposed a further, even more radical step. This was that the government of those provinces, through the sovereign's viceregal representatives, would no longer be responsible to London. He recommended that part of the government in respect of domestic affairs be conducted still by the Crown. Still, the Crown acted on the advice of ministers responsible to the colonial legislature. Not the crown acting on the advice of the British ministers. There, we see the beginning of a separate Canadian crown.

The main tension between the colonies and London was removed at one stroke. They were self-governing, with foreign affairs and defence remaining with London. Full independence would only be a matter of time. But that would be achieved by evolutionary change, not revolution or war.

The British Commonwealth emerges.

This evolutionary move to independence in Canada, Australia and New Zealand originated because the rule of law and all its benefits came with the settlers of each new colony at its very foundation. The British Empire was changing.

It was in Adelaide in 1884 that Lord Rosebery, later the British prime minister, described this trend accurately by stating that the Empire was now a Commonwealth of Nations. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, it was even recognised that the colonial governments had some limited right to deal with foreign powers. A half-hearted move to develop an imperial federation went against this trend. It commanded little support.

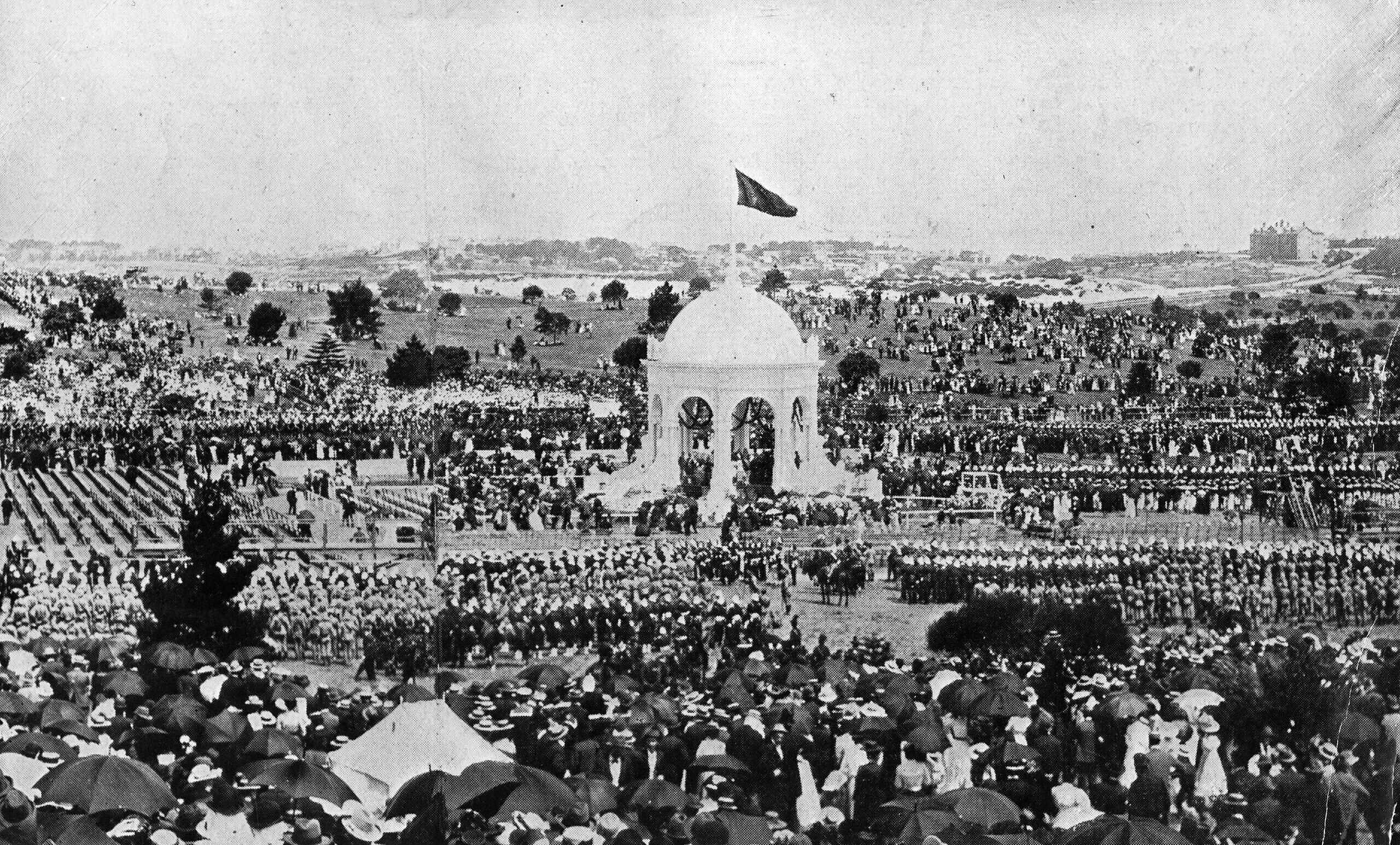

By 1917, at the Imperial War Conference, it was formally agreed that a readjustment of the constitutional relations in the Empire should be made based on a full recognition of the dominions (as the self-governing colonies came to be called) as "autonomous nations of an Imperial Commonwealth". At the Versailles Conference at the end of the First World War, Australia (and the other dominions) signed the Treaty of Versailles and became a full founding member of the League of Nations.

In 1920, Canada and the United States entered into full and separate diplomatic relations with one another. In 1923, the unfettered right of the dominions to enter into treaties was confirmed. Unlike the British, the dominions did not sign the Treaty of Lausanne with Turkey in 1923. The substantial obligations Britain agreed to in Europe under the Treaty of Locarno in 1925 did not extend to the dominions.

These developments were not initiated by, but were recognised in, the celebrated Balfour Declaration of 1926, which affirmed that the dominions were "autonomous communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate to one another in any respect of their domestic or internal affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the crown and associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations".

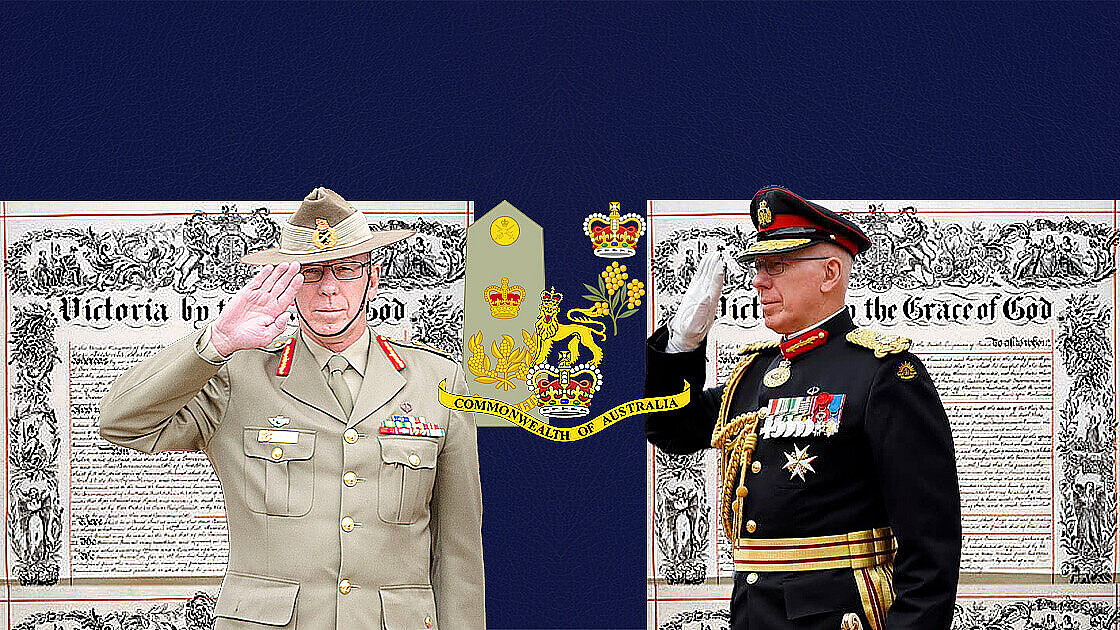

From 1930, governors-general were to be appointed by the sovereign on the advice of the dominion government. They were to continue in their principal role as the constitutional umpire and auditor in the dominion. They had in 1926, already lost their other subordinate role as representatives of the imperial government. This was to go to the high commissioners, who would represent commonwealth governments in other capitals.

The change flowed from an earlier decision in 1926 that a governor-general holds "in all essential respects, the same position in relation to the administration of public affairs" in the dominion concerned "as is held by His Majesty the King in Great Britain, and that he is not the representative or agent" of the British government.

In 1930, the first Australian governor-general, Sir Isaac Isaacs, was appointed on the advice, indeed at the insistence, of the Australian prime minister. The King had earlier suggested that there was an advantage in having a governor-general who had no connections with the local political scene and who was already personally known to him.

When Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, the reaction of the dominions was not uniform. Eire (now the Republic of Ireland) decided on neutrality. Canada and later South Africa declared war. The Australian Prime Minister, R.G. Menzies, in announcing the declaration by Britain, declared that "as a result. Australia is at war".

It was becoming clear that the old concept of a single indivisible imperial crown was no longer tenable. There were now several crowns. In 1937, Ireland (Eire) became or became close to being a republic, a fact accepted by the other members.

The Indian proposal

In 1942, the British government accepted that an independent India could secede from the Commonwealth. Burma did so in 1947, as Ireland did in 1948, first securing a treaty with Britain that confirmed the special relationship between them. In 1947, when India became independent, she indicated she wished to become a republic but to stay within the commonwealth.

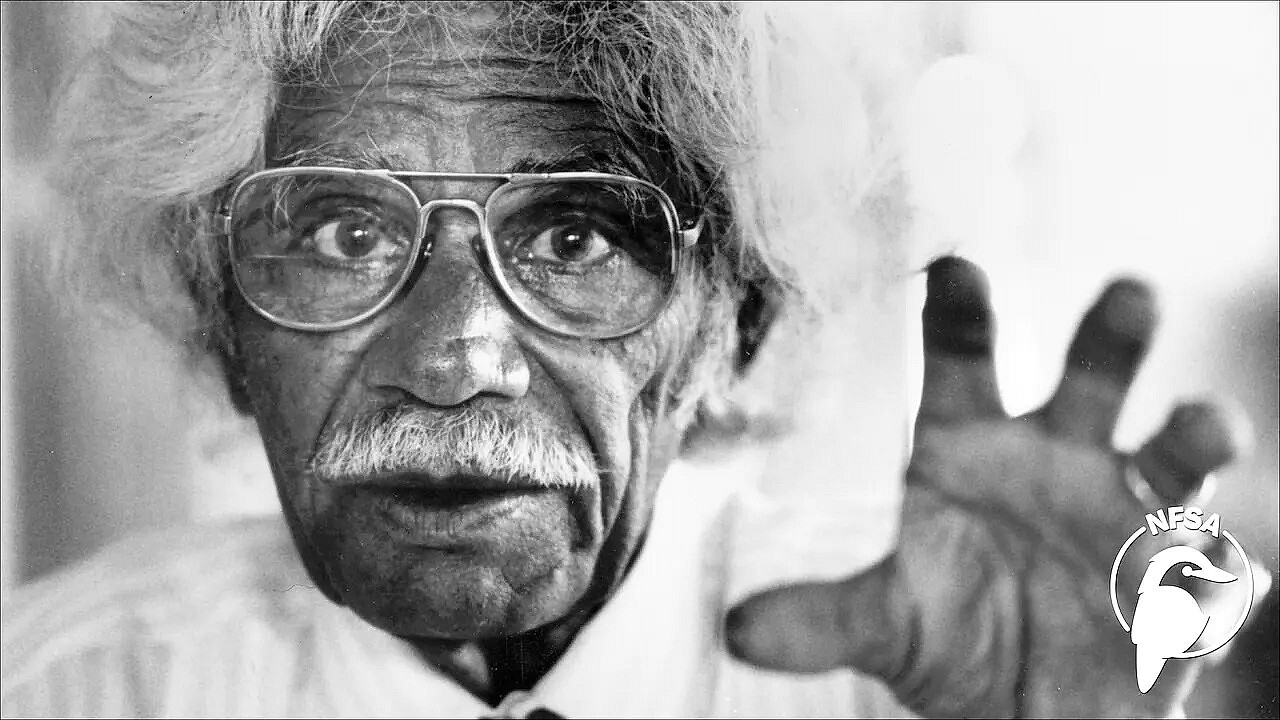

It had long been clear — at least to those with a vision —that independence would, in due course, be granted to the other colonies in Asia, Africa, and the West Indies, for there was no reason why other people should not enjoy the same rights that for example, Australians and Europeans enjoyed. The imperial authorities had already recognised the inherent equality of the races of the Empire.

For instance, in 1856, the British insisted on a common role of voters — not one based on race — in their colony in South Africa. The Colonial Secretary had declared in 1897 that the imperial tradition made "no distinction in favour of, or against race or colour".

This liberal tradition sometimes ran counter to the views of the white populations in the settled colonies. This was particularly true of Australia, where responsible governments frequently adopted policies in relation to both the indigenous people and immigration that caused tensions with governors and colonial secretaries. This aspect of our history is often forgotten, perhaps conveniently so.

The British Commonwealth became the Commonwealth.

In 1948, the Commonwealth could have denied the newly independent India, which wished to remain but become a republic. But this was likely to have led to the exclusion of many, if not all, of the new Commonwealth countries that might wish to follow India. In other words, the Commonwealth would have become principally a white man's club. So all of the members agreed that India could continue as a member, even as a republic.

This procedure was followed until 2007 when a Realm became a republic. ( A Realm is a Commonwealth country recognising The Queen as its Sovereign or monarch.) India accepted "the King as the symbol of the free association of its independent member state and as such the head of the Commonwealth". And on the death of King George VI, his daughter, Queen Elizabeth II, was, by common consent, proclaimed "Head of the Commonwealth".

All of the old dominions, with the exception of South Africa, have remained in the Commonwealth as realms, with Elizabeth II as Queen, and so have twelve other former colonies. These, with the UK, number sixteen. Another six member states have national monarchies: Brunei, Lesotho, Malaysia, Swaziland, Tonga and Western Samoa. The remainder — all "new" Commonwealth states — are republics.

The Commonwealth of Nations and the 1999 Australian referendum

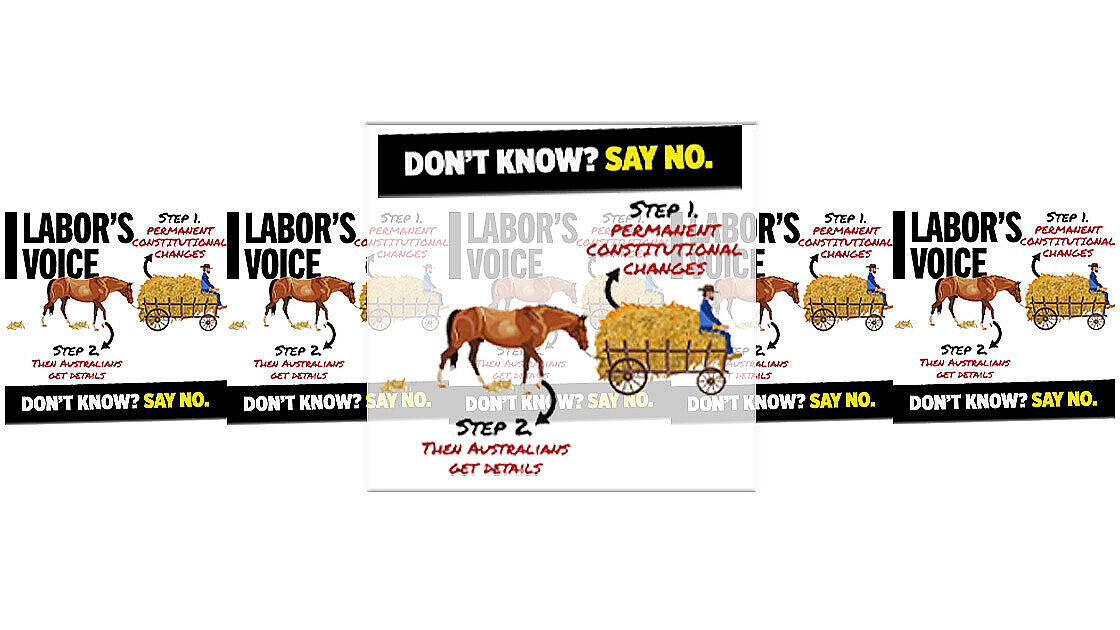

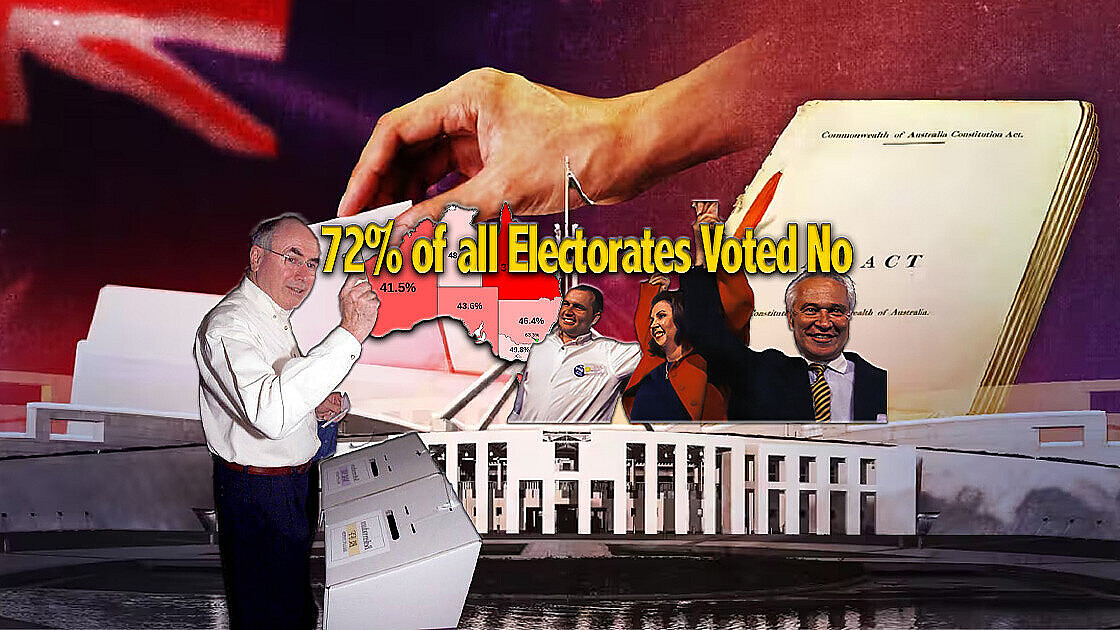

All parties to the republican debate in Australia in the nineties indicated their wish that whatever the outcome of the referendum, Australia should remain a member of the Commonwealth. Indeed, the ARM has consistently stated, without qualification, that if Australia becomes a republic, it will continue as a member of the Commonwealth. And the Australians for Constitutional Monarchy has just as consistently pointed to the actual practice from 1947 that the consent of all other members of the Commonwealth is necessary.

In May 1999, Attorney-General Daryl Williams repeated the ARM view during a speech: “The Australian Government proposes that the name, Commonwealth of Australia, be retained and that Australia continue to be a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. Australia will not need to reapply for membership in the Commonwealth if it becomes a republic, as constitutional status is not a criterion of membership. This would mean that if the proposed change were supported, Australia would still participate in the Commonwealth Games.” (Canberra Times, Monday, 10 May 1999)

ACM believed this statement should not go uncorrected. It was part of a wider message — that the change was only symbolic and was quite simple. So the ACM National Convenor, Professor David Flint, stated that were Australia to become a republic, any of the other 53 commonwealth governments might be able to block its continuing membership of the Commonwealth.

He pointed out that in 1960, South Africa withdrew after becoming a republic, accepting that not all other governments would consent to its continuing membership. And Fiji's membership was deemed to lapse in 1987 after it became a republic, and it became clear that there was some opposition to its continuing membership. He agreed that the attorney-general was correct in saying that constitutional status is not a criterion of membership. But convention clearly requires that a change of this nature be approved, or at least not opposed by any one of the other 53 governments.

No Republic—ACM has always believed that all of the consequences of change, legal, political and financial, be placed before the people. They are all entitled to be in a position to cast an informed vote.

The ARM then issued a press release on 13 May under this heading: "Australians for Constitutional Monarchy talk nonsense about Australia's membership of the commonwealth."Professor Flint’s warning was dismissed as "silly", "an insult to the intelligence of all Australians", and "shameful".

In what one journalist described as a "battle of press releases", he then asked, "Why not check the facts on commonwealth membership?"

Former Prime Minister Bob Hawke appeared on a national radio programme and said Professor Flint was a liar. But Professor Flint said ACM had never claimed that Australia would be excluded from the Commonwealth if we were to become a republic.

The Commonwealth Secretary General’s ruling

In the meantime, Professor Flint had written to the Secretary General of the Commonwealth, Chief Emeka Anyaoku. His Excellency replied on 18 May 1999. The Commonwealth Secretariat approved ACM releasing his letter, provided the text was published in full.

It reads: “Thank you for your letter of 11 May 1999, which I saw on my return from overseas travel.“You are right in your understanding of the procedures within the Commonwealth when a country changes its constitutional status to that of a republic. On being notified of the change by the government concerned and in the light of an express wish to continue Commonwealth membership, I would then contact all other Commonwealth countries seeking their concurrence for the change. In the normal course of events, this process is not more than a formality and was most recently followed when Mauritius became a republic on 12 March 1992.”

When Professor Flint released this, he said that if Australia were to become a republic, it would be outrageous if our continuing membership were put into issue. He said that would be condemned by all Australians. But he warned that were Australia to become a republic, some groups in Australia might lobby other Commonwealth members. They already do so in other international bodies. They could argue that our policies were in breach of Commonwealth principles. “What would happen is impossible to predict,” he said.

“Let us hope any change did not coincide with similar diplomatic incidents to those where an Australian prime minister once called a Commonwealth prime minister "recalcitrant" or its legal procedures "barbaric", as happened under two previous governments.” He pointed out that our presence in the important forum for European-Asia economic issues, ASEM, had been denied by the veto of just one country. The last summit, held in London on 3-4 April 1998, was chaired by Tony Blair, the United Kingdom Prime Minister and then president of the European Union Council. It brought together the 15 European Union States, the European Union Commission, the seven ASEAN countries (Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam), as well as the People's Republic of China, Japan and Korea.

Professor Flint said it was an important meeting, the second in a series. Australia wanted to be there and should have been there. Our presence was desired by all the other 25 states – except one. We were vetoed. Lest it be thought this is of no importance, the summit itself confirmed the importance of the Europe-Asia partnership. It approved a number of initiatives taken since the first summit in Bangkok. And it laid the foundations for ASEM's future development. Two separate statements were adopted, one of which concerned the financial and economic crisis affecting several Asian countries. The statement on the crisis in Asia stressed the parties' interest in restoring economic stability and the need for swift implementation of reforms in the countries affected. The final overall statement covered the development of political dialogue on important regional issues such as Cambodia, Korea, and the EU enlargement.

All of these issues were of great and continuing concern to Australia. He said we should have had an input. And would have but for one country's veto. Malaysia decided that we should not be there.

Professor Flint warned that in recent years, Australia had been disappointed in some of its plans for our role in international forums — quite often after the holding out by well-known ARM supporters that we would be successful. One was in relation to the secretary-generalship of the Commonwealth itself, the other our candidature for a seat on the Security Council.

He said the ARM and its supporters were well aware that Australia does not have the enormous resources of other countries (and groups of countries) to buy international influence. Nor does it have superpower clout.

As an old Western democracy – actually multiracial, tolerant and welcoming – it is too frequently portrayed as insular, intolerant and racist, even by elements within Australia. It is an easier target for international busybodies than those countries with authoritarian governments, indifferent to human rights, where an increasingly intolerant monoculturalism prevails.

Our membership of the Commonwealth, he said, is precious. It is a club in which we play – and have since its foundation always played – a significant role with countries which are particularly close to us. It allows us to compete in the Commonwealth Games. Professor Flint said that rather than denying the existence of the documented Commonwealth convention that when a realm becomes a republic, all other members must agree to its continuing membership, the ARM should be investigating how best to ensure this agreement.

After all, he said, it is the ARM that is proposing change. The onus is on the proponents of such change both to demonstrate and assure Australians that it will be as simple as they claim and that there will be no unexpected results.

The Commonwealth changes the rules.

In 2007, the Commonwealth Heads of Government changed the rules, providing that “when an existing member changes its formal constitutional status, it should not have to reapply for Commonwealth membership provided that it continues to meet all the criteria for membership.”

This, of course, was an acknowledgement that, until then, change from a Realm to a republic had to be placed before all the members, any one of whom could have objected.

The change may not be as effective as the Heads of Government intended.

Much will depend on the interpretation of the proviso, “provided that it continues to meet all the criteria for membership.” And who is to interpret that? The inescapable conclusion is that it is for each member of the Commonwealth to interpret.

If this had been in force in the past, the result would probably have been the same.

Historical Background

A 2007 Commonwealth report on membership made the important point that ‘we cannot withdraw the Commonwealth from the historical context in which it was born. We are not tied down by it, but we must respect it.

That part of the report, which gave a historical background of the Commonwealth, follows.

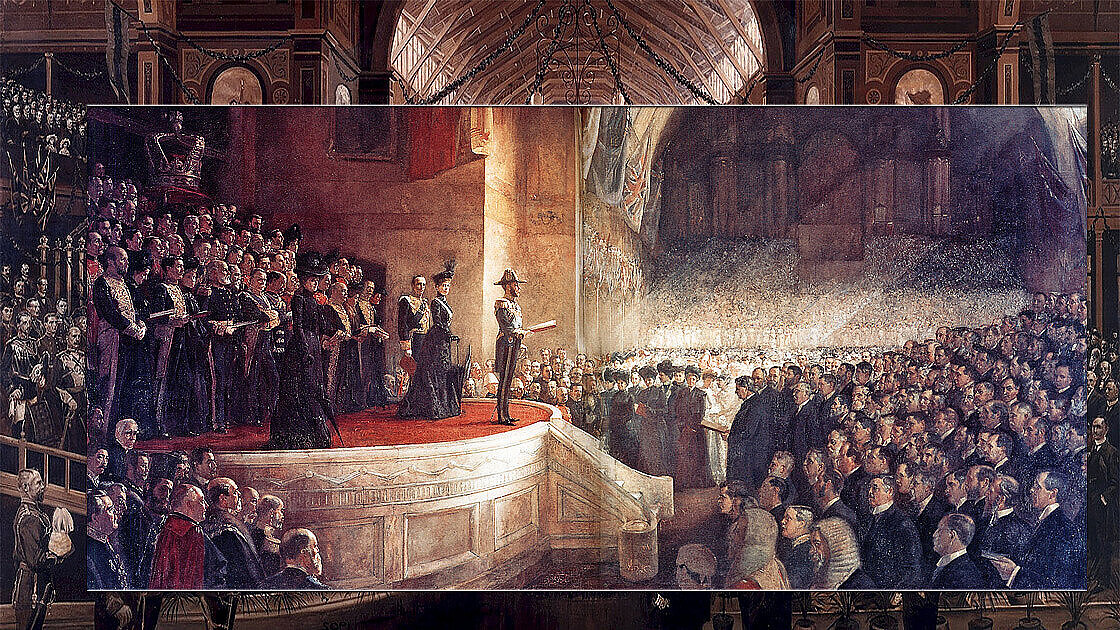

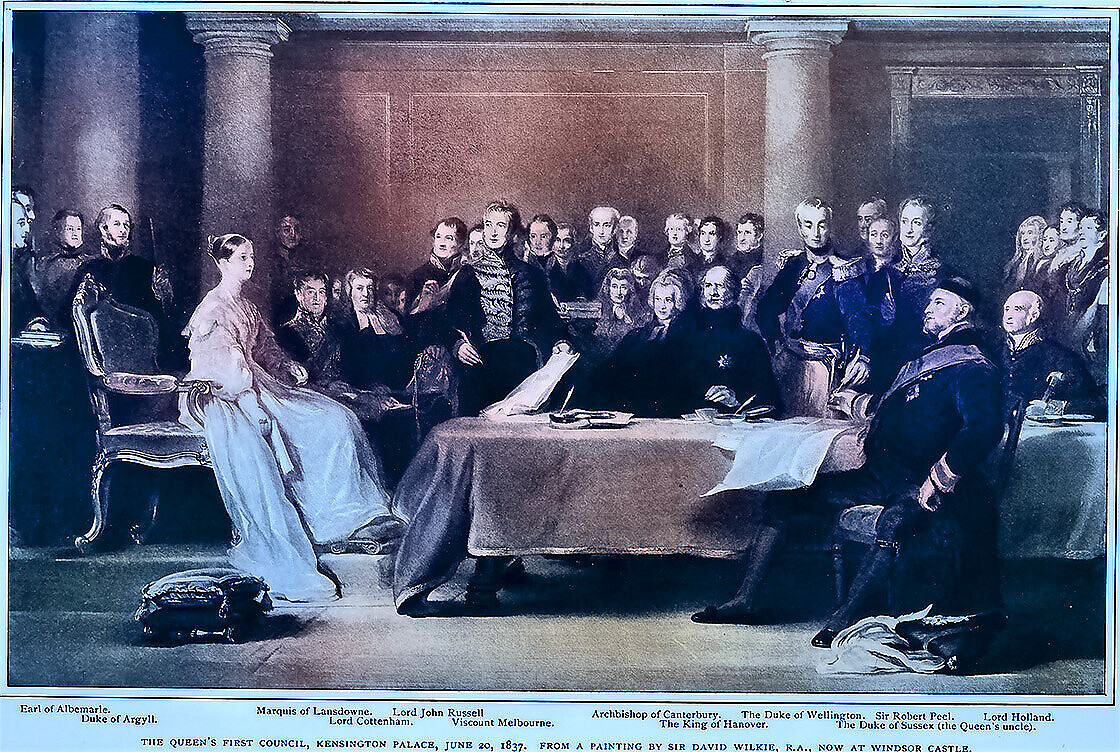

The world’s oldest political association of sovereign states

Viewed in this context, the Commonwealth may be recognised as the World’s oldest political association of sovereign states. Its origins are traceable to 1869–1870 when representatives from self-governing colonies Met unofficially to demand consultative arrangements. The first Colonial The conference was convened in 1887 at the time of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. The decision was made in 1907 to hold regular meetings confined To Prime Ministers. Membership in these meetings was accorded to those Countries that had attained ‘responsible government’ on the British Parliamentary model.

The name ‘Commonwealth’ came to be applied to an association unique in its modes of operation and in the width and depth of its voluntary, unofficial and non-political networks. ‘Commonwealth’ originally meant nation-state, and ‘Commonwealth of Nations, as used from the mid-19th Century, signified a family of self-governing, i.e. politically independent, countries. The term ‘British Commonwealth of Nations was used formally. From 1921 to 1948, it was subsequently abbreviated to ‘the Commonwealth’.

Independence of members

The regular conferences began as intimate gatherings of six member

countries—Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, and

South Africa. New members were soon added, and definitions of their

The status was demanded. India, although not yet self-governing, was invited

To send representatives from 1917. Southern Ireland, as the Irish Free

The state was added in 1922. South Africa’s demand for a declaration of its

independence and an Irish compilation of ‘anomalies and anachronisms.’

in its legal status were addressed by the formula agreed in 1926, which

defined the ‘position and mutual relation’ of the members as autonomous,

equal in status, owing common allegiance to the Crown, and freely

Associated.

These principles were embodied in the preamble to the Statute of

Westminster (1931), which also declared that the Crown was the symbol

of the free association of the members. Equality and voluntary association

between independent states thus became fundamental principles of the

association.

India's proposal

New members were increasingly added after the Second World War,

beginning with Asian nations—India and Pakistan in 1947 and Ceylon

(Sri Lanka) in 1948. When India, the largest member, adopted a

republican constitution, it sought to remain in the Commonwealth and

this was agreed by the existing members. The Declaration of London

(1949) provided that, in place of the sole remaining formal bond

of common allegiance to the Crown, the Republic of India accepted

The King is the symbol of the free association of the independent

member nations and, as such, the Head of the Commonwealth. Malaya

became a member in 1957 as the first national monarchy in the

Commonwealth.

Expansion came next from Africa. When Sudan and the Gold Coast

demanded independence, there was resistance to their becoming

Commonwealth members, especially from South Africa, and there was

talk of a ‘mezzanine status’ and a two-tier Commonwealth. Sudan,

geographically the largest African territory, became an independent

republic outside the Commonwealth in 1956. Advice that if the Gold

Coast was denied full membership, and the rest of Africa eschewed the

Commonwealth led to Ghana’s full membership in 1957. Nigeria, the

most populous African state, followed in 1960.

In the same year, the ‘wind of change’ induced an acceleration of the

pace of change as France, Belgium and Italy created new states in Africa

and the United Nations General Assembly called for the end of colonial

status. There were twelve African Commonwealth members by the end

of the 1960s, a decade that saw three other major landmarks.

Small states

First, Cyprus became independent in 1960, but there was resistance to

the idea of full membership for a population of only half a million in a

state guaranteed by Greece, Turkey, and Britain. It was realised that there

were many more small states in the wings and that if Cyprus became a full

member, it could be the precedent for over thirty more potential members.

The Prime Ministers appointed a committee of senior officials to review

the matter. Their recommendation was to deny full membership of

the Commonwealth to a country that qualified to be a member of the

United Nations would be frustrated with much that the Commonwealth

stands for. Cyprus joined in 1961 and was followed in 1962 by Jamaica

and Trinidad and, later, by nine other Caribbean countries. In subsequent

years, small states would comprise the majority of the members.

Apartheid

Secondly, on the same day that Cyprus was welcomed to the 1961 Prime

Ministers’ Meetings, Dr Verwoerd withdrew South Africa’s application

to emulate India and stay in as a republic. On the eve of the meetings,

Julius Nyerere had published a statement that soon-to-be-independent

Tanganyika might eschew a Commonwealth that included the apartheid

regime. Led by the Canadian Prime Minister, the leaders condemned the

South African policy of apartheid. The Republic of South Africa remained

out of the Commonwealth for thirty-three years.

Secretariat

The third landmark was the creation in 1965 of the Commonwealth Secretariat, which was suggested by the leaders of new member-countries, Ghana, Uganda, and Trinidad, and was dubbed by Milton Obote as the

Commonwealth’s ‘declaration of independence’ from Whitehall. The

The secretary-general was made responsible to the heads of government

collectively and took over responsibility for organizing the Commonwealth

conferences.

The next round of new members came from the Pacific. Western Samoa

(independent since 1962), Fiji and Tonga (independent in 1970) attended

the Singapore Heads of Government Meeting (the first to be styled

CHOGM) in 1971. In Singapore, member countries also adopted the

Declaration of Commonwealth Principles.

Southern African issues

The first thirty years of the Secretariat’s life were dominated by political

problems of Southern Africa—the illegal regime in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe,

South Africa’s occupation of South West Africa in defiance of UN

resolutions, and, above all, apartheid in the Republic of South Africa.

The resolution of these issues, assisted by considerable unified effort from

the Commonwealth, resulting in further enlargements of the membership.

Zimbabwe became a member after elections under Commonwealth

monitoring in 1980. Namibia became the fiftieth member in 1990,

bringing the Commonwealth to the same size as the first UN General

Assembly. South Africa returned after thirty-three years in 1994, following

its first multi-racial polls and the election of President Mandela.

In a notable new development, Cameroon (only a part of which had

once been under British rule) joined and attended the Auckland CHOGM

in 1995. The former German colony of Kamerun had been divided into

British and French Mandates, later UN Trust Territories. By referenda in

1961, the British Trust Territory of Northern Cameroons voted to join

Nigeria. Southern Cameroons chose to join the Republic of Cameroun

, which constituted two Anglophone north-western provinces that

accounted for about one-fifth of the total population, the remainder being

largely Francophone. Cameroon had applied to the 1993 Limassol

CHOGM, partly as an endeavour to placate secessionist movements in

the Anglophone provinces and also to project the country more widely

in the international community.

Heads of Government decided that Cameroon could be invited to the

1995 CHOGM provided that democratic reforms then underway met

the criteria of the Harare Commonwealth Declaration. A Commonwealth

mission headed by Dr Kamal Hossain of Bangladesh, Chairman of the

Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative reported positively in July 1995.

The President of Cameroon was welcomed at the Auckland CHOGM,

where it was also decided to accept Mozambique into membership—the

first member that had never had a constitutional link with a

Commonwealth member.

Surrounded by member countries, Mozambique had come to be known

as a ‘cousin’ state of the Commonwealth. Its rail routes and ports were

vital to the trade of the land-locked Commonwealth members.

Independent Mozambique from 1975 had been a vital ally in Zimbabwe’s

freedom struggle. It sent observers to CHOGMs from 1987, the year

when the Commonwealth Special Fund for Mozambique was created to

furnish technical assistance. In 1995, President Mandela proposed that it

should be admitted ‘as an exceptional case’, and Mozambique was accepted

as the fifty-third member. At the same time, Heads of Government

requested the Secretary-General to establish the IGGCM to advise on

criteria for assessing future applications for membership.

New patterns of consultations

The 1997 Edinburgh CHOGM established a new and wider pattern of

consultations. As Head of the Commonwealth, the Queen addressed the

conference for the first time. The first Commonwealth Business Forum

met beforehand and created the Commonwealth Business Council. The

first Commonwealth Centre for Civil Society Presentations (precursor of

later Commonwealth People’s Forums) met, as did the first

Commonwealth Youth Forum. This tri-sector pattern of consultations

between government, civil society, and business continues to evolve in

the 21st Century.

In 1997, Heads of Government also received and endorsed the IGGCM

report, which is the starting point for the discussions of CCM.

Five conclusions on membership

The above survey of the growth in membership suggests five conclusions

relevant to the discussions of the CCM:

1. Growth of membership has been continuous, and this has changed

the character of the association.

From a nucleus of five nations, which

had the character of an unwritten military alliance in the era of the two

world wars, the addition of the Asian, African, Caribbean, and Pacific

nations marked the transition to a unique multilateral association with a

predominance of small states and an emphasis on development and

poverty eradication.

2. There were always anomalies.

India, the largest member, attended

the conferences long before it became independent. Newfoundland, the

pioneer small state, attended Commonwealth Conferences but stayed

out of the League of Nations. The premiers of Southern Rhodesia and

Burma were invited as observers before their country’s independence.

An association with a majority of republics has a monarch as symbolic

Head.

3. There was always resistance to new members but eventual acceptance.

Some leaders in the early days strenuously opposed the idea of republics

in the Commonwealth. There was opposition to Ghana, to Cyprus and

the small states, and to Mozambique. But, after due consideration, positive

decisions were made in each case and led to the continuing growth and

strengthening of the organisation.

4. There have been many comings and goings but countries that left have generally returned.

Newfoundland gave up self-government in 1933

And became a Canadian province in 1949. The Republic of Ireland left

in 1949. South Africa was out for thirty-three years, Pakistan for seventeen,

and Fiji for ten. Nigeria’s membership was suspended from 1995 to 1999.

Pakistan was suspended-from-Commonwealth-councils between 1999 and

2004 following a military coup, as was Fiji in 2000–2001 and again, in

2006, and Sierra Leone in 1997.

(Following the overthrow of the elected government of Tejjan Kabbah by a military council in

1997, CMAG suspended the ‘illegal regime’ in Sierra Leone from the Councils of the

Commonwealth. However, the Kabbah Government continued to be recognized by the

Commonwealth even while their leader was in exile. President Kabbah’s return to Freetown in

March 1998 brought an end to this anomalous situation.)

Zimbabwe quit the Commonwealth in December 2003 after being suspended from councils in March 2002.

There were also countries with historic constitutional links, which, after

gaining their independence from Britain, never joined the

Commonwealth—Burma (Myanmar), and, in the Red Sea/Middle East

region, Egypt and Sudan, Palestine and Jordan, Iraq and the Gulf States,

Aden (South Yemen) and British Somaliland (which became part of

Somalia).

5. The Commonwealth is an association of peoples as well as states.

While the contemporary tri-sector pattern of business, civil society, and

youth forums dates only from the 1997 CHOGM, a non-governmental

organizations are of very long standing. The press, parliamentary, and

universities associations pre-dated the First World War, and there were

Unofficial Commonwealth Relations Conferences held at five yearly

intervals between 1933 and 1959, following on from the Imperial

Conferences and Prime Ministers’ Meetings. In these consultations,

politicians, professionals, academics, military officers, and businessmen

debated Commonwealth and international affairs, and women began to participate as delegates before they did in the political Commonwealth.

Since the creation of the Commonwealth Foundation in 1966, some thirty new professional associations have been founded. With the widening of the Foundation’s mandate in 1980, new organisations devoted to care and welfare have been added, and the Foundation has published groundbreaking guidelines for non-governmental organisations' good practices.

After the creation of the Commonwealth Business Council, it has organised well-supported Business Forums, encouraged public/private partnerships, and fostered training in corporate governance.

Regular civil society consultations on a regional basis are made before CHOGMs, which are now preceded by a week of activities that include a People’s Forum organised by the Foundation, a Youth Forum, a Human Rights Forum, a Business Forum, and inter-faith dialogues. The richness and diversity of the tri-sector contributions make for a very significant part of the Commonwealth’s uniqueness and contemporary attractiveness.

[Source: Commonwealth Secretariat Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting Kampala, Uganda, 23-25 November 2007 Pre-CHOGM Foreign Ministers Provisional Agenda Item 2(iv) HGM(07)(FM)3 CHOGM Provisional Agenda Item 4 HGM(07)5 Membership https://www.ituc-csi.org/IMG/pdf/CHOGM_2007_Communique.pdf