Argentina

Republicans raised the constitutional status of Argentina. Richard Woolcott said that an Argentinian had told him it would be impossible to conceive of the King of Spain also being King of Argentina.

Australia and Argentina

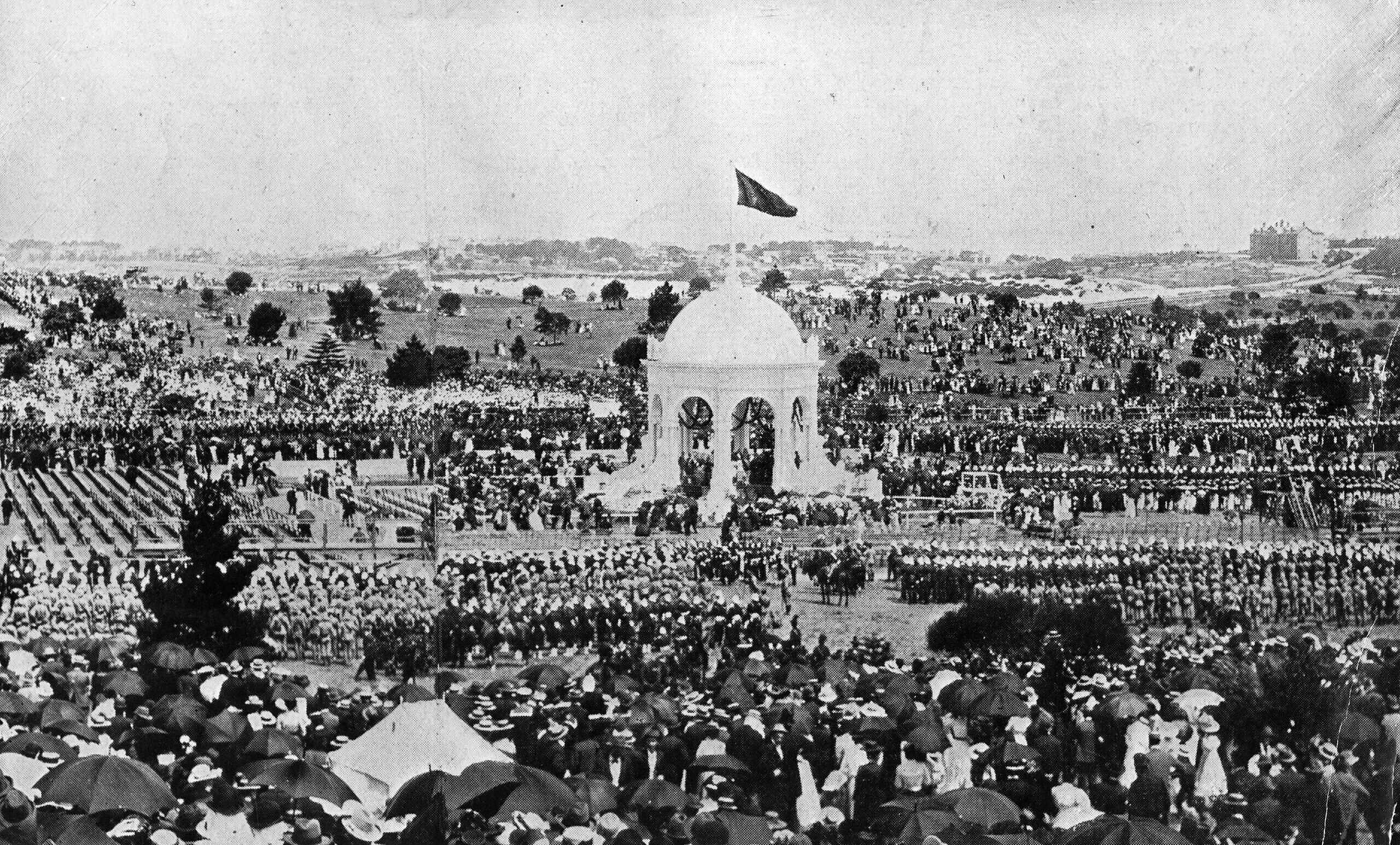

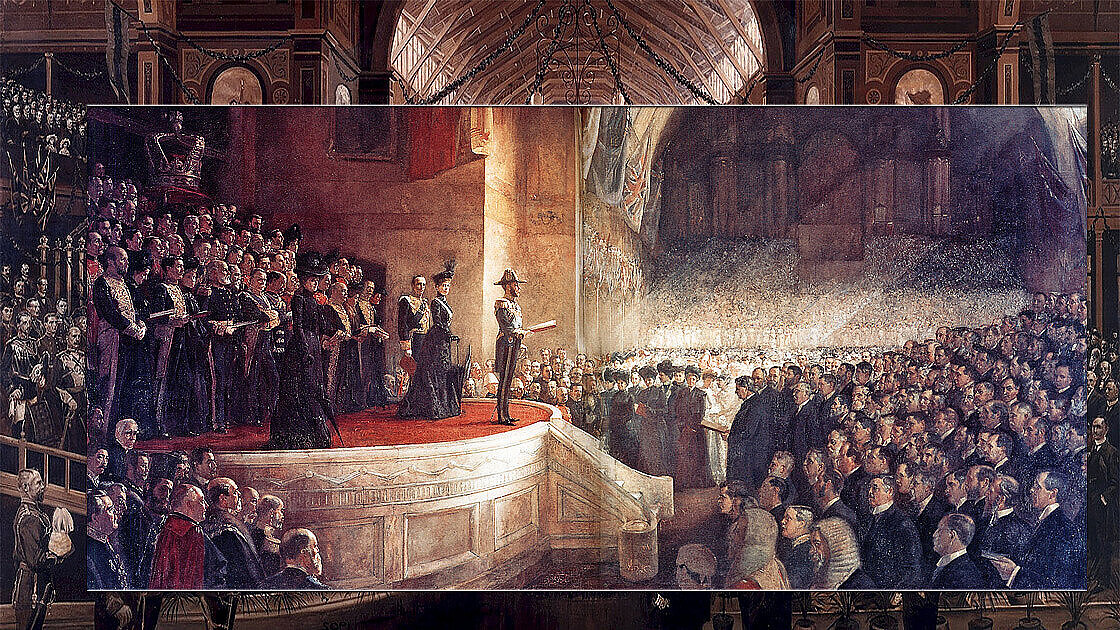

Our Federation was born on the first day of the new century, 1 January 1901. A comparison with another similar country demonstrates the extraordinary success of the Australian Federation. In 1901, Australia had one of the highest incomes per head in the world, an honour it shared with another former settled colony, Argentina.

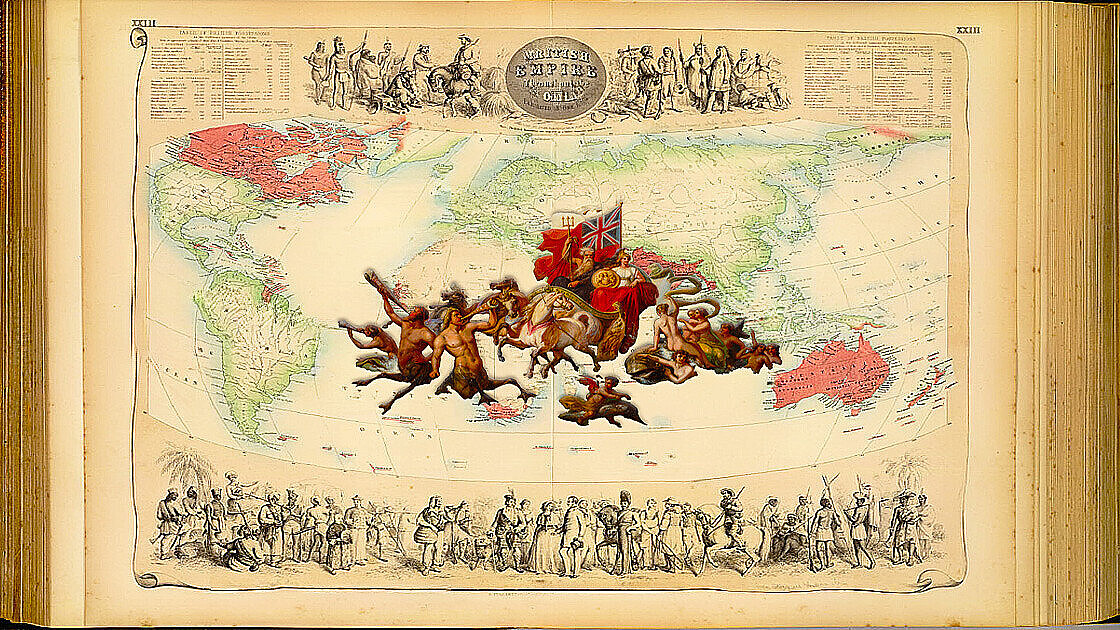

We had much in common. Both were countries of European set¬tlement, both supplanting an indigenous population, although Argentina was treated much more harshly. Both attracted large-scale immigration, and both imported much of their essentially Judaeo-Christian culture and their European language. Both were developed with substantial British investment, and both were rivals for shares in the lucrative British meat market.

But our histories since then could not have been more different. Australia remains one of the world's oldest continuing democracies —Argentina has alternated between a symbolic democracy behind which a wealthy plutocracy ruled and bouts of dictatorship, usually military. The last resulted in the "disappearance" — the murder — of thousands of Argentinians, the precise number of which is still unknown. The economy has undergone a series of crises. The legal system is discredited, and unlike Australia, Argentina has contributed little to the worldwide struggle for freedom and democracy, certainly nothing like Australia. More Australians died fighting in the First World War than any other non-European power, even the US! We were one of the very few who fought from the very beginning to the end of the Second World War. Argentina was neutral, at least for most of the duration, of both. Today, the Argentinian economy is ravaged, and the people are poor. Australia, in Purchasing Power Parity terms (PPP), is amongst the world's tenth richest (Buckingham, 2001).

The Argentinian economy collapsed in early 2002. Rioting mobs set fire to the economics ministry. The economic supremo, Domingo Cavallo, the architect of tying the peso to the US dollar, had already gone in late 2001. President Fernando de la Rua resigned, and interest payments on Argentina's massive debts were suspended. By the end of the year 2001, de la Rua's successors had also vacated the presidency. In just two weeks, Argentina had had five presidents!

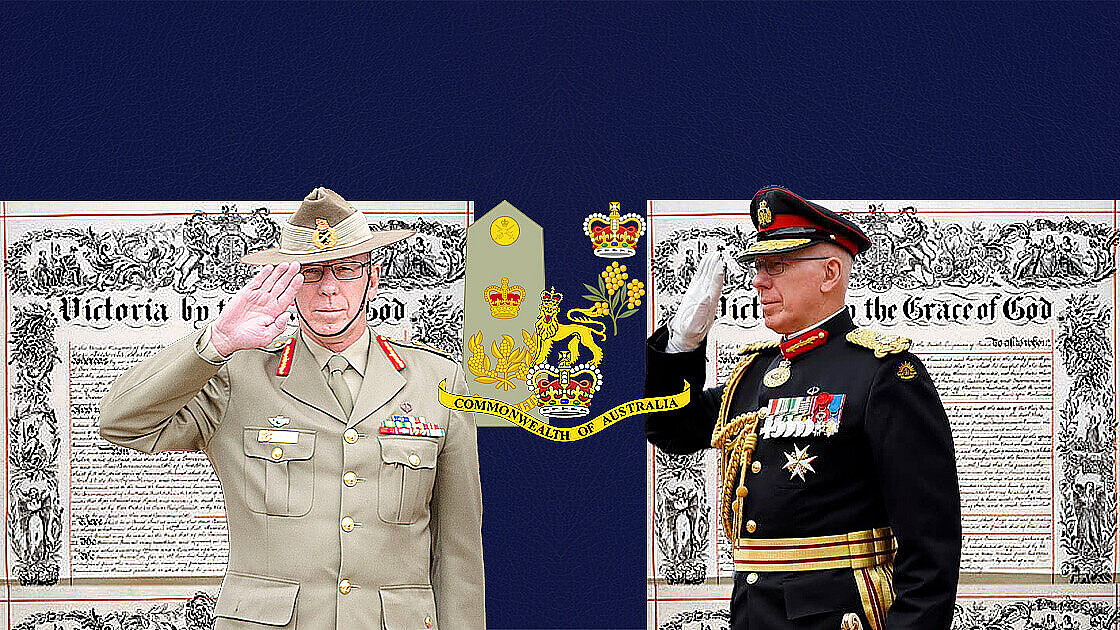

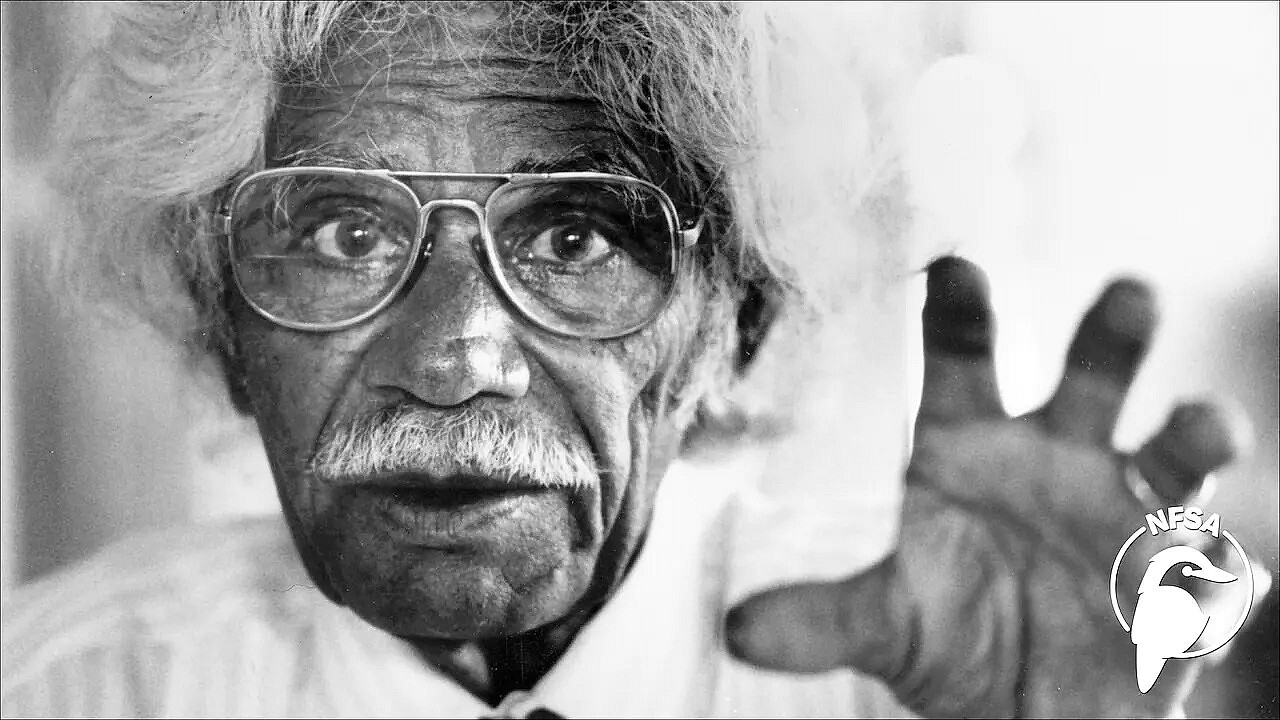

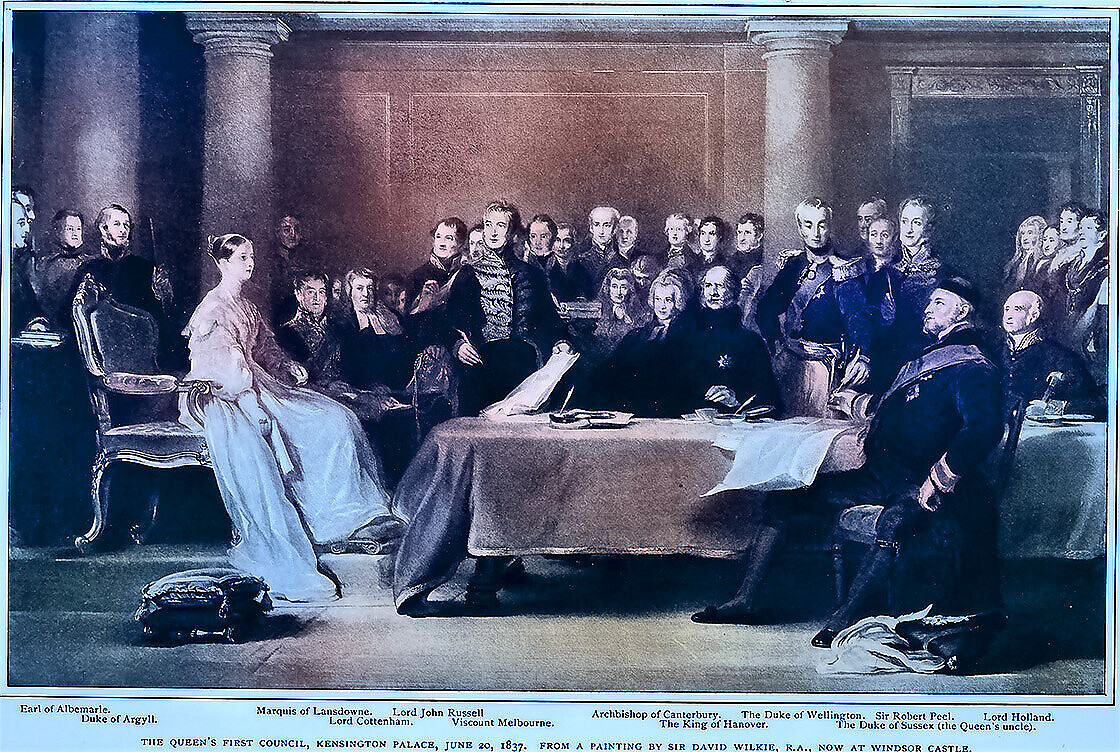

Now the Argentinian people are in no way inferior to the Australians — just as hard-working, as honest and as brave. What is wrong? The difference is in the underlying institutions and values of the two countries. While both began with the benefits of a Judaeo-Christian culture and an advanced European language, Australia, from its beginnings — even as a penal colony — enjoyed both the rule of law and the central role of an institution above politics but under the law, the Crown. It was inevitable that self-government under the Westminster system would soon follow. That was not at all inevitable for Argentina. Why? Because the colonial power, Spain, did not enjoy these benefits and, therefore, could not give them to her colonies. While Argentina had to fight for her independence, Australia was given hers.

The institutions we have — democracy, the rule of law, parliament, a responsible government, the Westminster system, an independent judiciary and an institutional heart beyond political capture, namely the Crown — are the foundations on which our country is governed peacefully, democratically and effectively. While those institutions have all been adapted and Australianised, they still allow us to withstand the enormous stresses that are inevitable in the life of a nation. That is how we have played such an extraordinary role in the world's conflicts, the last being the liberation of East Timor. That is how we maintained our democracy both under the cold winds of world economic crises, especially the Great Depression, and during terrible wars.

Not so many years ago, certain Australian gurus were warning — and some even predicting — that Australia would go down the Ar¬gentinian path of economic disaster. Paul Keating, then Treasurer, even used the term "banana republic".

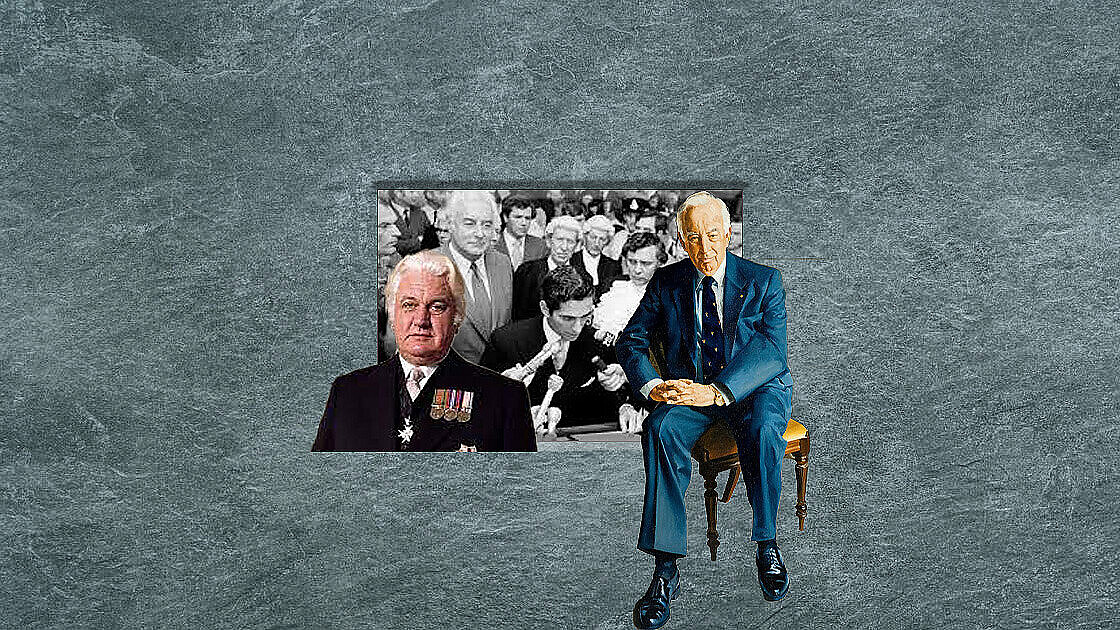

During the height of the last Argentinian crisis, I wrote along these lines for The Age, published on 26 December 2001. I concluded, "We may well cry for Argentina, but we perhaps should have rejoiced more fulsomely than some public intellectuals have over our remarkable success. On 5 January 2002, The Age published a piece by Mr Peter Costello, the Federal Treasurer. He said I had argued that Argentina lacks good institutions and does not have a monarchy! Rather, he said, Argentina's economic problems are merely the consequence of recent bad economic management. But Argentina's problems are deeper than that. I remember, in 1994, a minister in Buenos Aires lamenting the state of the courts, especially their lack of independence and even corruption. Argentina had, during the 1970s and early 1980s, put up with her armed forces playing politics again, this time murdering thousands. And unlike Australia's, Argentina's armed forces rarely go to war —except of course, the ill-fated Falklands adventure. Whenever there was a coup or when those in power engaged in illegal or unconstitutional acts, there was no authority in Argentina to bring them to heel.

Stable democratic systems are few and far between. Even in the first half of the twentieth century, when Argentina seemed to function reasonably well, this was really a facade for an old, powerful oligarchy, one which Juan Peron replaced with a populist dictatorship. Development had been principally financed by British investment; Peron na¬tionalised most of that, with disastrous consequences.

Argentina was never burdened, as we were, with heavy contributions in people and money to the campaign for freedom and democracy, particularly in the two world wars. In the Second, her government even flirted with the Nazis. Australia continues to live under one of the oldest and most stable democratic systems the world has ever seen and remains one of the richest. Argentina is probably the only country to have fallen from First to Third World status. A rich country has been laid waste.

Yet both countries have produced governments which have mismanaged the economy. In fact, most countries do. But once we realise our mistake, we vote them out, and the system ensures they go. The army does not try to do this for us by putting the generals in power. And one of the advantages of our Federation is that the damage governments can sometimes do is necessarily limited. So whatever damage the John Cain and Joan Kirner governments did, this was kept essentially to Victoria. As was the case with the Brian Burke Government in Western Australia.

A Federal Government can do worse, as with the large accumulated debt left by the Keating Government and the inflationary spiral created by the Whitlam Government when it spent about 50% more than its income. But this is still less damaging than a unitary government. The difference between our success and Argentina's failure is not between the floating of our dollar and Argentina's peso-dollar parity. Both were to a great extent, forced on the governments by circumstances then prevailing. The difference is that we had inherited and then made our own stable institutions and sound conventions within a tried and tested constitutional system.

Mr Costello ridiculed me by pointing to the US as a stable republic. The experience of the United States itself is, however, testimony to the difficulty of changing core institutions. The United States actually spent the better part of its first century of independence trying to establish a sound currency to replace the pound. The saying "not worth a Continental" refers accurately to the value of her first currency, termed continental paper. This was followed by a succession of crises of truly Argentinian proportions — something which Australia, Canada, and New Zealand did not experience. Why? Because our transition to independence was evolutionary, not revolutionary.

On the ABC Foreign Correspondent programme broadcast in April 2002 about the Argentinian crisis of 2001-2002, members of an Argentinian family indicated they wanted, desperately, to emigrate to Australia or Canada. They said that 80% of their friends and relatives wanted to leave, too. A former minister in the Government of President Carlos Saul Menem said that Australia and Argentina are similar countries but with one important difference. This was: "Australia has British institutions. If Argentina had such strong institutions, she would be like Australia in ten or twenty years." Australia does indeed have that rare asset in the world: strong and stable institutions, as well as the values that go with them and which underscore them.

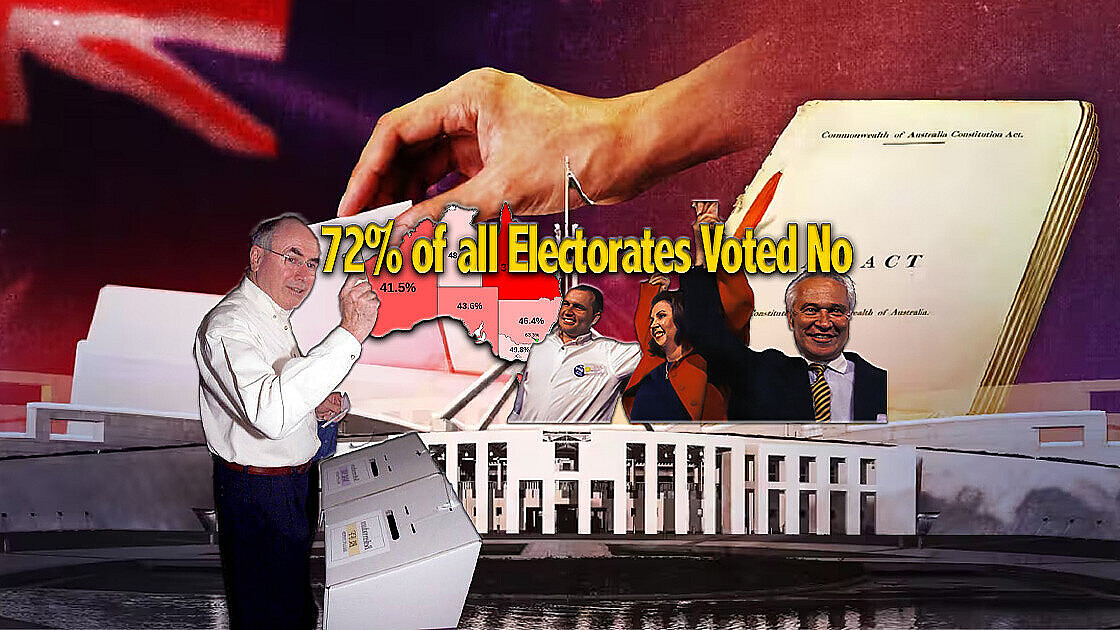

The lesson is not so much to find a perfect government, although we should, of course, keep those in office who demonstrate prudence and competence in the nation's affairs. Dr Helen Irving, a Republican academic, has called for a wholesale review of the Australian Constitution. Her reason? It recalls the celebrated French elite comment, "Well, it may work in practice, but does it work in theory?" (Ca marche en pratique, mais en theorie ... ?) (Sydney Morning Herald, 31 October 2002).

Rather, the lesson is to maintain, and not recklessly undermine, a constitutional system which has been shown to work and work well over an extended period of time. And there certainly are not many of those in the world.