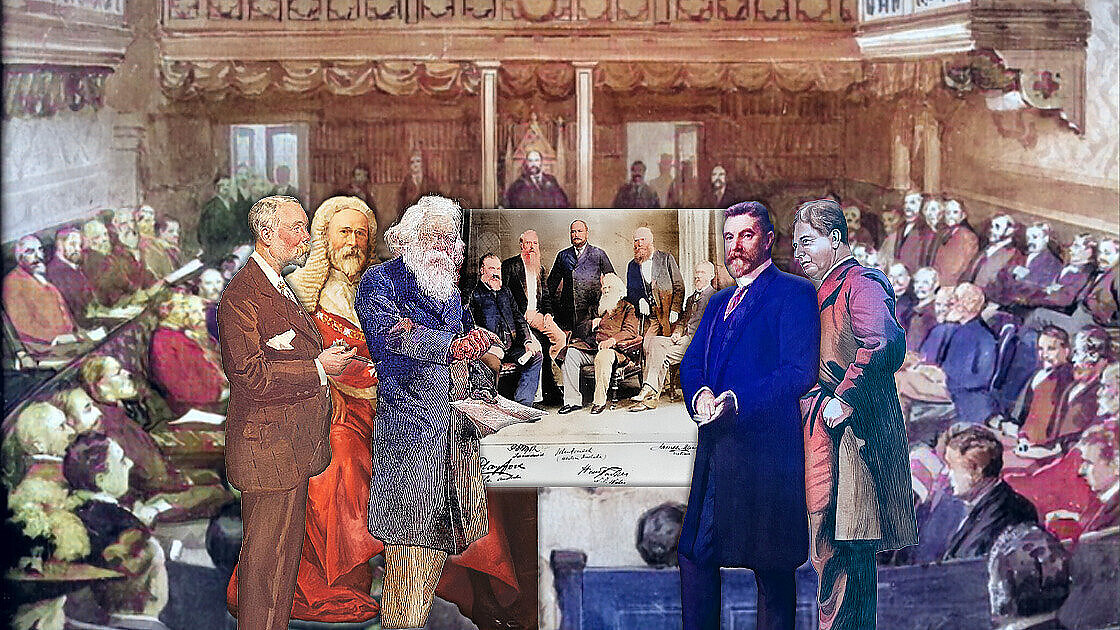

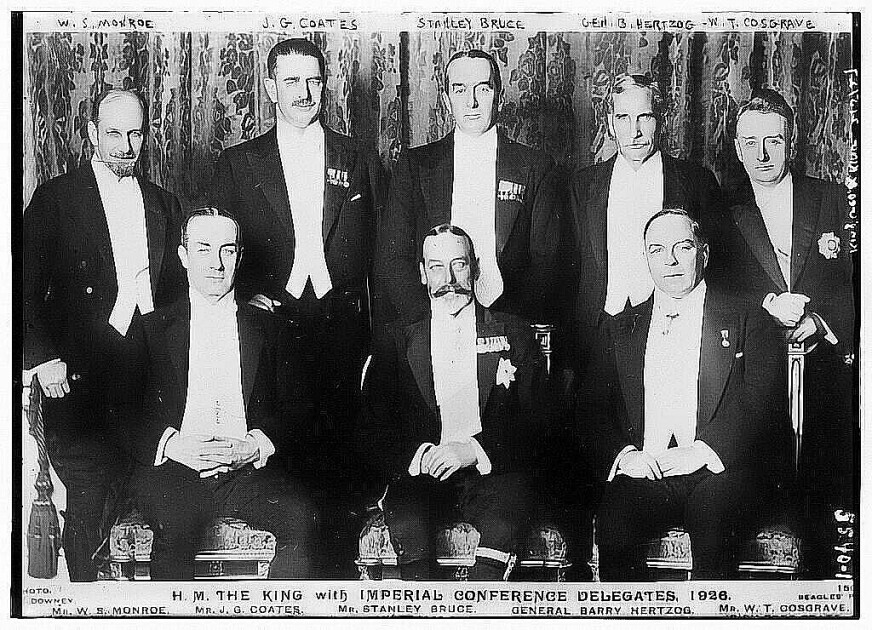

[The King with His Prime Ministers 1926 (left to right): Walter Stanley Monroe (Newfoundland), Gordon Coates (New Zealand), Stanley Bruce (Australia), J. B. M. Hertzog (Union of South Africa), W.T. Cosgrave (Irish Free State). Seated: Stanley Baldwin (United Kingdom), King George V, William Lyon Mackenzie King (Canada).]

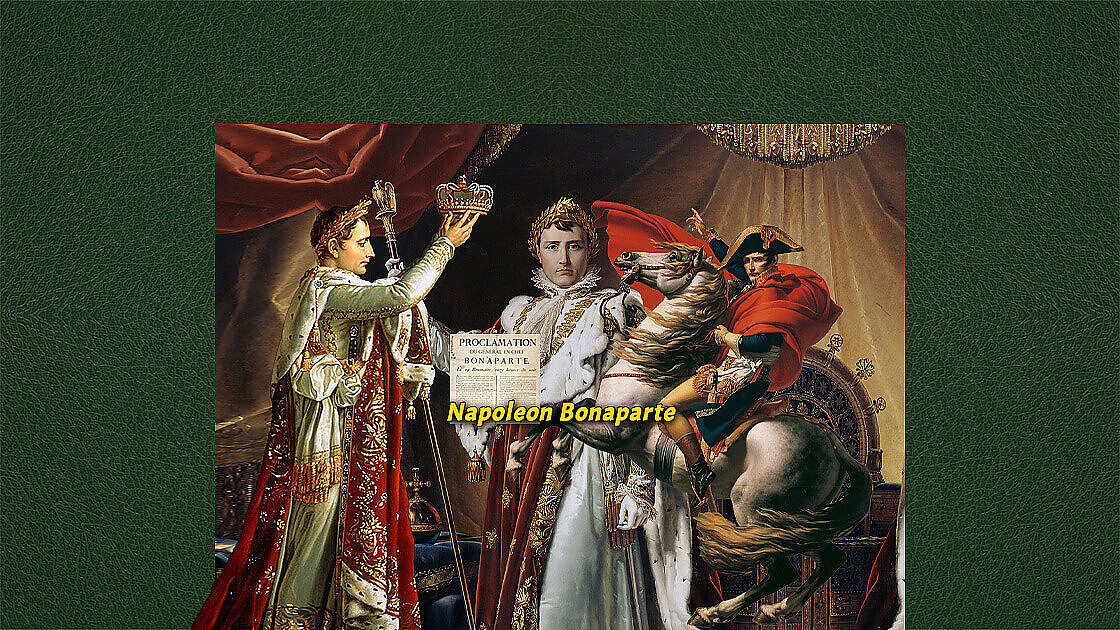

Australia's Origins

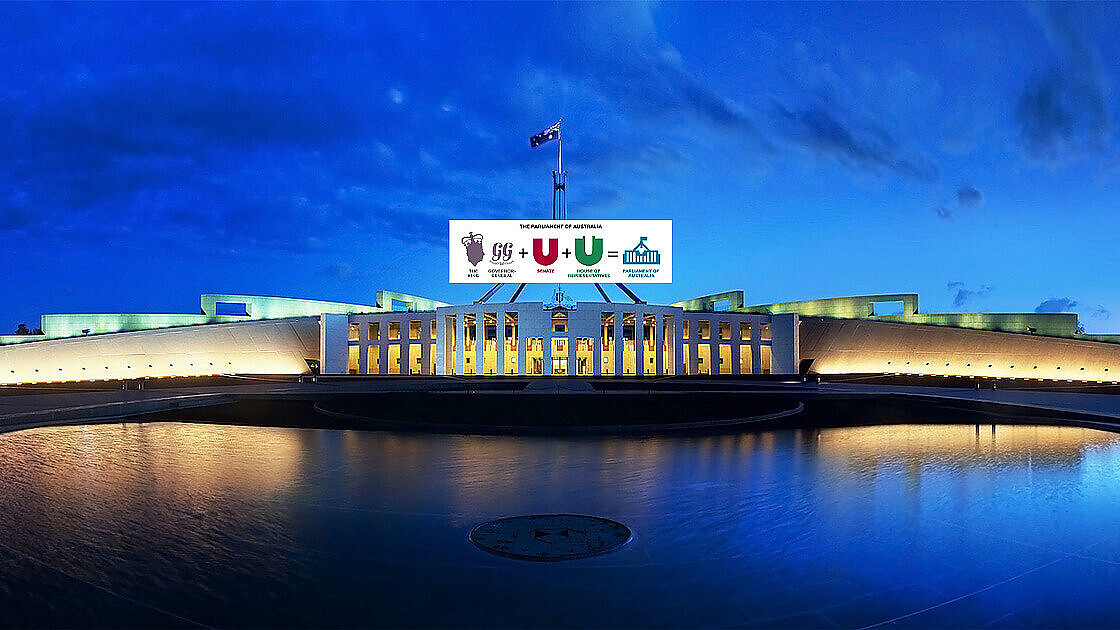

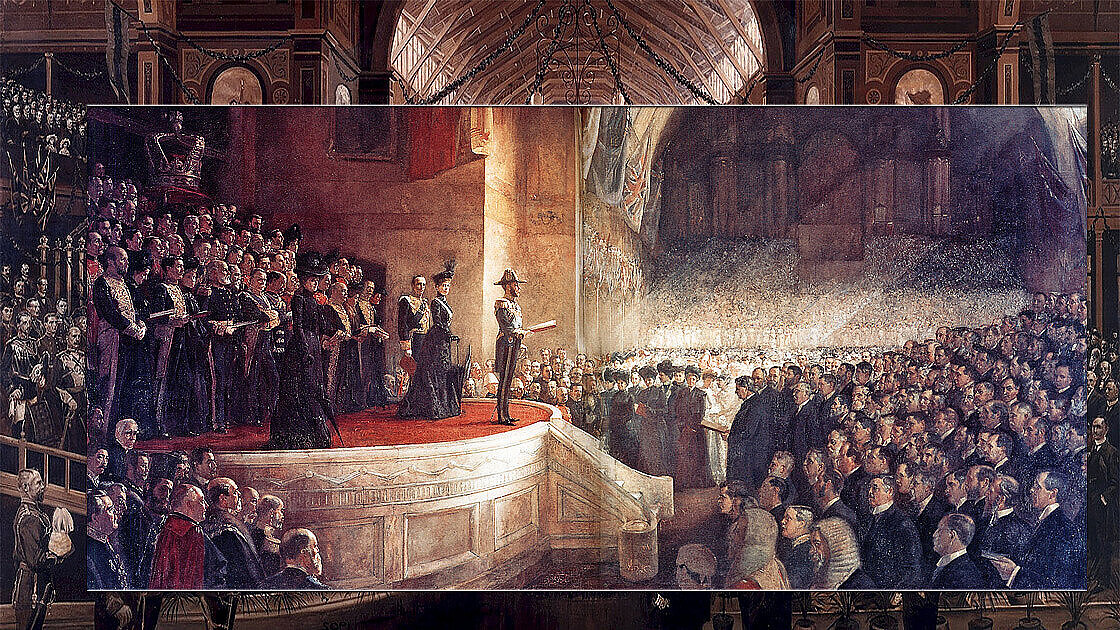

Australia's Origins: The Crown, as Australia's oldest legal and constitutional institution, holds a position of utmost importance. Introduced with the settlement in 1788, it has remained steadfast at the centre of our constitutional system, guiding and shaping our nation's history.

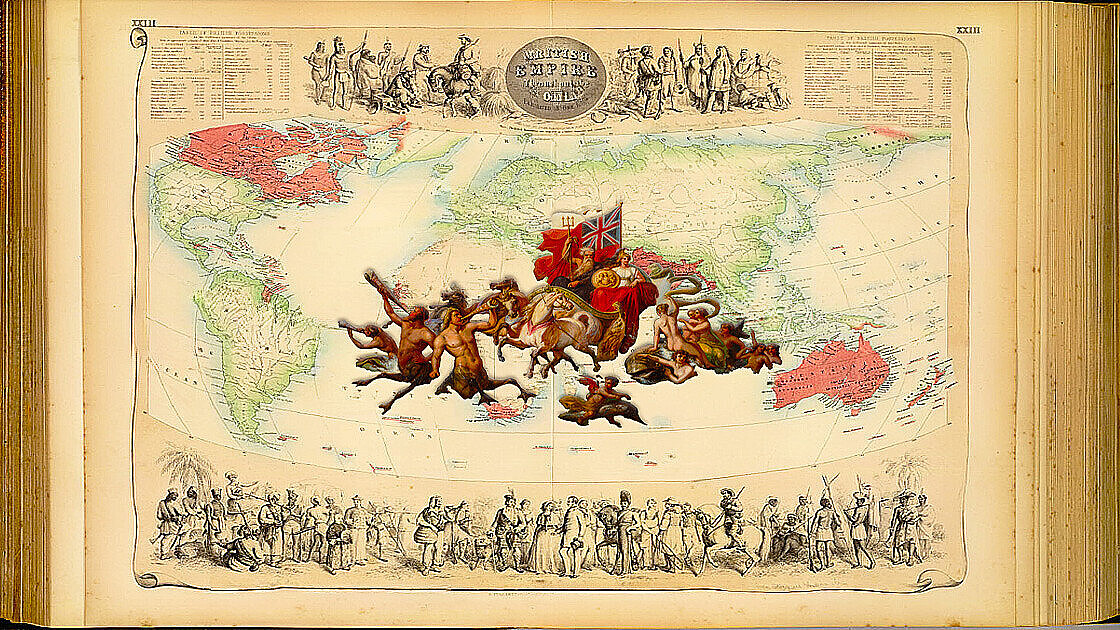

In 1770, Lieutenant James Cook charted the east coast of Australia and claimed it for Great Britain. He returned to London with accounts favoring colonization at Botany Bay (now in Sydney). The First Fleet of British ships, which arrived at Botany Bay in January 1788, played a crucial role in establishing the first penal colony. The History of Australia (1851–1900) refers to the history of the people of the Australian continent during the 50-year period which preceded the foundation of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901.

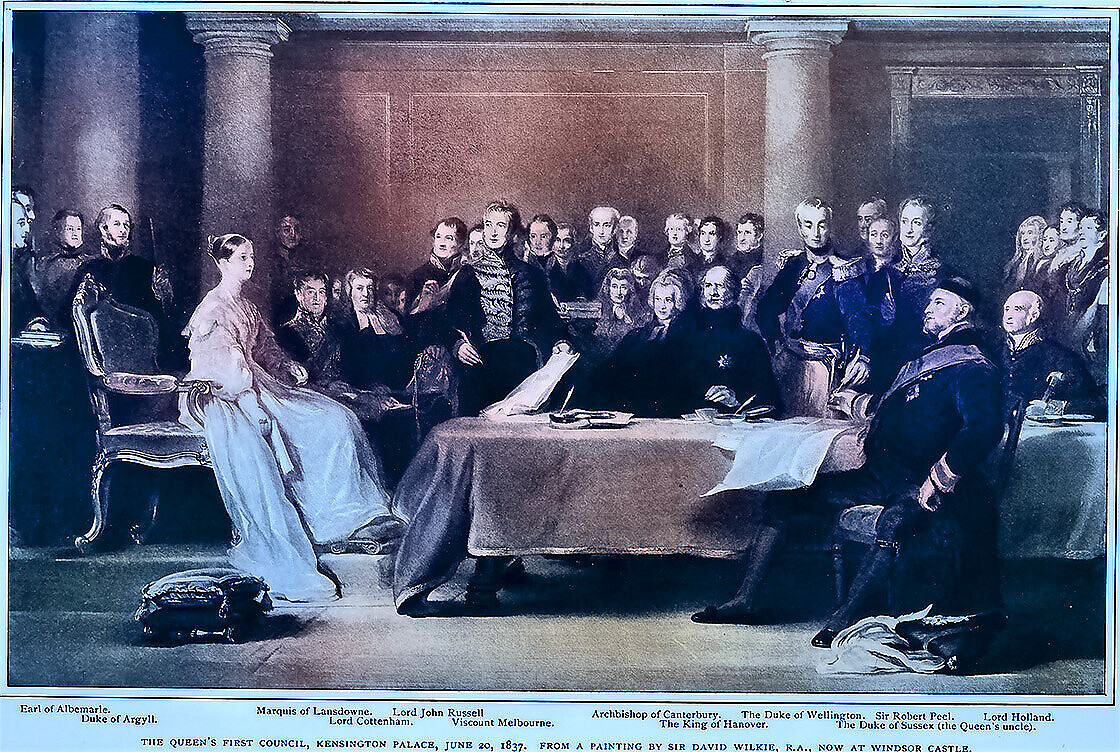

In 1926, as a result of decisions taken at an Imperial Conference of Prime Ministers in London, the single Imperial British Crown began to divide into the Australian, Canadian, New Zealand, British, and other Crowns of other Realms. (Realm comes from an old French word meaning a kingdom.)

Each Realm has long been entirely independent. Each one recognizes The Queen or The King as Sovereign or Monarch.

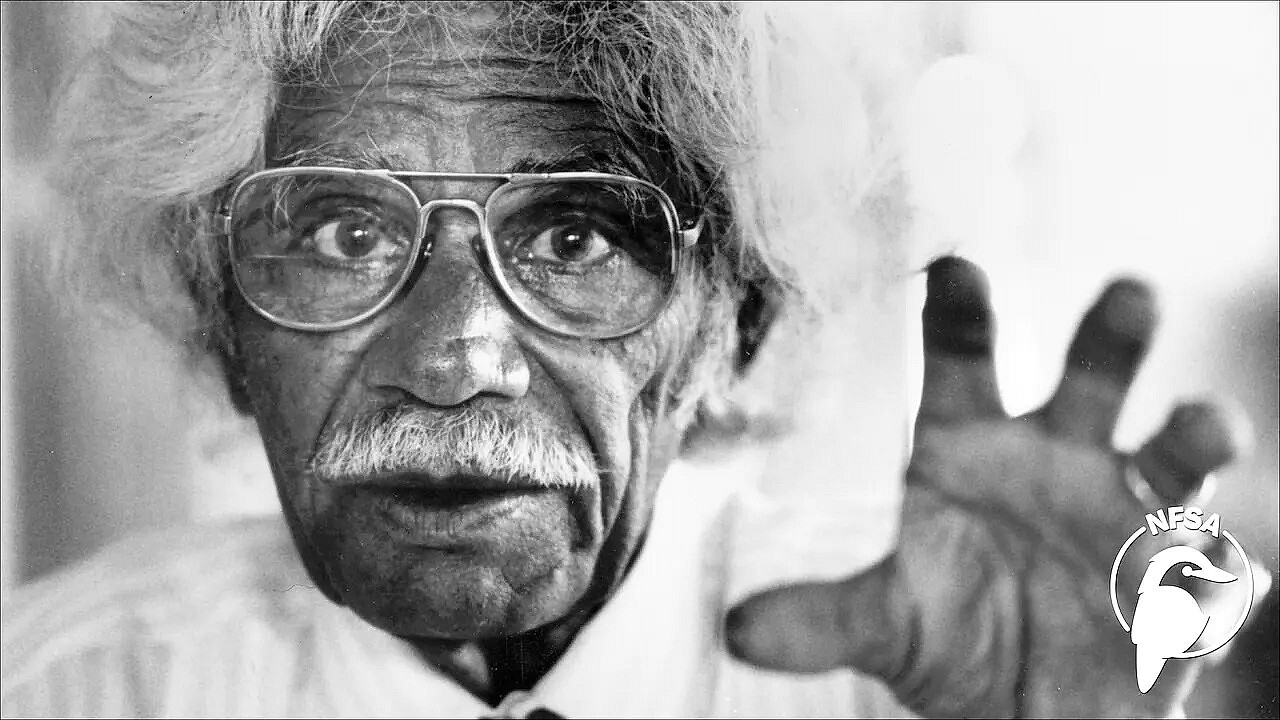

Although the Australian states became self-governing colonies in the nineteenth century, and the Commonwealth of Australia was established in 1901, Australia was not yet fully independent. Nor were Canada and the other self-governing Dominions, now called Realms.

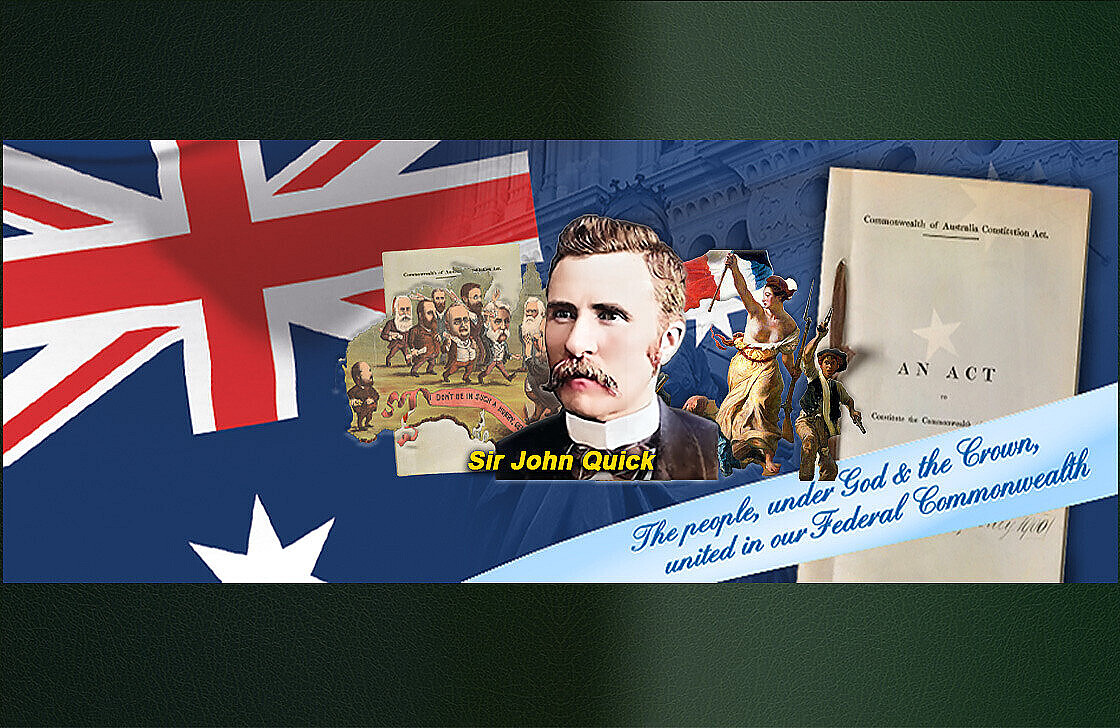

However, the Australian Constitution was the first one approved by the British, where the constitution could be changed without the need for British legislation, which indicated a considerable degree of freedom.

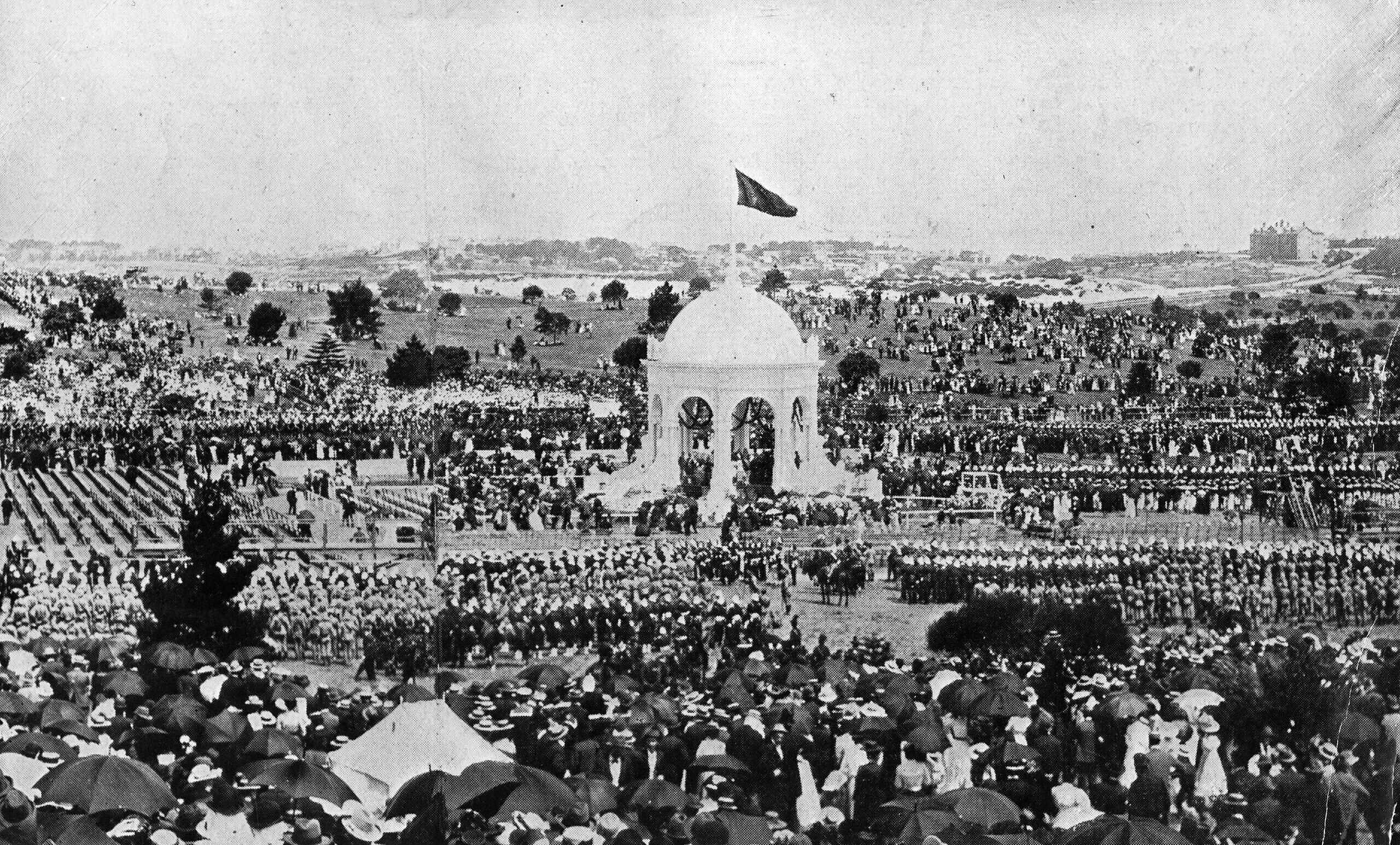

After the First World War, Australian representatives were involved for the first time in the negotiation and signature of a political treaty, the Treaty of Versailles of 1919.

As a result, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa became foundation members of the League of Nations, the precursor of the United Nations.

For Australia and these other Dominions, this was a significant step in their being recognized around the world as independent countries.

But until 1926, the Imperial Crown remained a single legal and political institution across the British Empire. At the local level, the Crown would be advised by local ministers in relation to day-to-day activities, but on the most important matters, for example, the appointment of a Governor-General. The Sovereign, then King George V, would act on the advice of His British ministers.

At the Imperial Conference that year, it was agreed under what came to be known as the Balfour Declaration that the United Kingdom and the Dominions, including Australia, Canada and New Zealand, were "equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs, though united by common allegiance to the Crown, and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations".

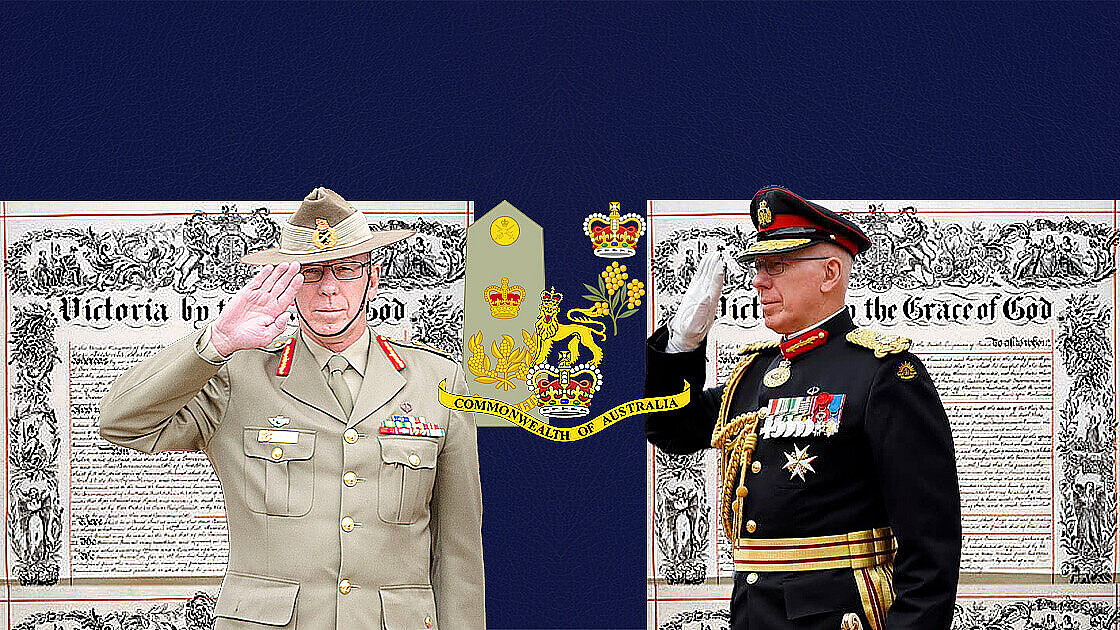

As a result, the Australian Governor-General would represent the Australians and not the Imperial Crown.

He or she would no longer be appointed on the advice of the British ministers but on the advice of the Sovereign’s Australian ministers, which in practice meant the Prime Minister.

It confirmed something which had already occurred - that the Governor-General he would “hold in all essential respects in relation to the administration of public affairs” in Australia as “the King did in the United Kingdom.”

The difference was that he was no longer accountable to British ministers and would no longer act as a conduit between the British and Australian governments.

High Commissioners appointed by each government would do this.

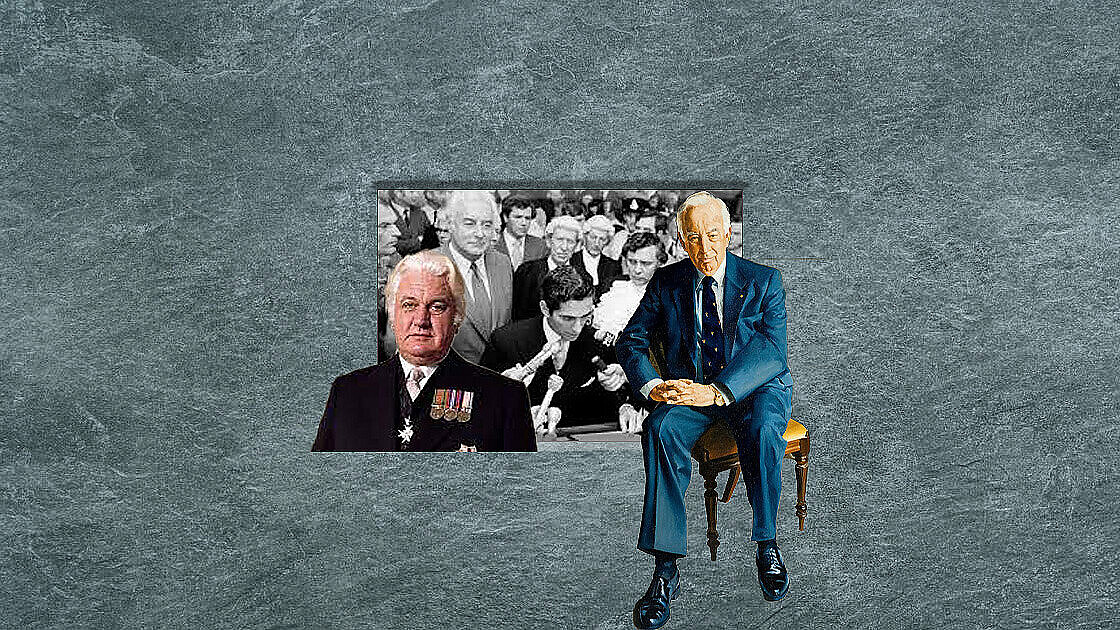

The Balfour Declaration of 1926 effectively declared independence for the Dominions. Some took advantage of this as soon as they could. Others took years.

As a result, the Imperial Crown began to divide into separate Australian, British, Canadian, New Zealand and other Crowns.

The legal position is that the Crowns of each are separate and distinct institutions but have the same Sovereign (the King or Queen), a point confirmed by the High Court of Australia in 1999 in the case of Sue v Hill.

This sharing of a Sovereign is well-known in international law and is called a personal union.

A Proclamation gave the legal effect of this separation of the Crowns under the resulting British legislation, the Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act 1927.

Then the Statute of Westminster,1931 confirmed the independent status of Australia and the other Dominions. It was adopted in Australia in 1942, and for legal reasons, backdated to the beginning of the Second World War in 1939: the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act, 1942 (Cth).

But at the request of Australia, the Statute of Westminster was not to apply to the Australian States.

This was because state politicians of all parties had less confidence in federal governments than British ministers in conveying their advice to the Crown on such matters as the appointment of governors and the reservation of proposed legislation for Royal Assent.

Accordingly, on State matters, the Sovereign was advised by Her British Ministers. Technically, the British Crown retained a vestigial role in Australian affairs until 1986.

It is important to understand that this was only because State governments trusted the British more than the Federal government. The States were not prepared to have the Prime Minister advise The Queen on State matters, for example, on the appointment of Governors or disallowing State legislation.

This was terminated under legislation passed by all Australian Parliaments and the British Parliament: the Australia Acts, 1986.

The Queen played a crucial role in agreeing to a solution that was unique to the Commonwealth. On State matters, The Queen would be advised by the Premier, a practice which does not apply in Canada.

That the British Crown was to play a residual role in Australia until late 1986 is not so surprising, given the peaceful way Britain transferred power to her former colonies.

Until 1982, the British Parliament could only change the Canadian constitution, but not because of any British wish to retain control. The Canadian government could not agree on how to amend its constitution.

This development demonstrates the genius of our evolving and enormously successful constitutional systems.