Constitutional Guardian

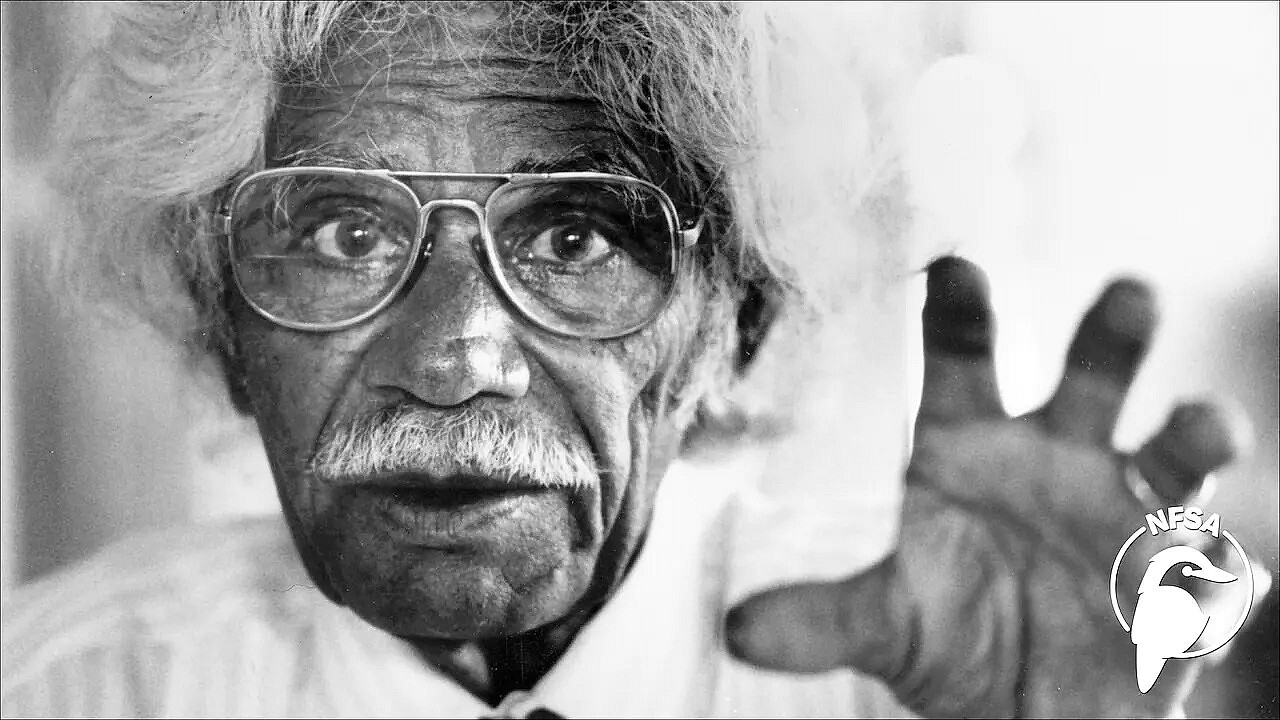

According to Sir Zelman Cowen, (AK, GCMG, GCVO, KStJ, QC (7 October 1919 – 8 December 2011) was an Australian legal scholar and university administrator who served as the 19th Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1977 to 1982), Said: the reserve powers of the Crown include the power to dismiss a ministry, to grant or refuse a dissolution, and to designate a prime minister. Few legal observers would deny the existence of the reserve powers, although in controversial cases, there is a debate on the manner and time of their use. In Australia, these powers are exercisable at the federal level by the governor-general. They are not reviewable by the courts, not being justiciable, nor is it for The Queen to review their exercise. It is, therefore, inappropriate for a viceroy to discuss their exercise in advance with the Sovereign. In addition, it is relevant at this point to recall that The Queen of Australia can alone exercise certain important powers of the Crown. These relate to the appointment and dismissal of the viceroys. This is normally done on the advice tendered in writing in an original document, but there is an argument that this, too, is in the nature of reserve power. Certainly, there are indications that it would be an error to regard The Queen as an automaton, assenting without question to advice, particularly that relating to dismissal.

The existence of these powers is an important constitutional check and balance on the exercise of power.

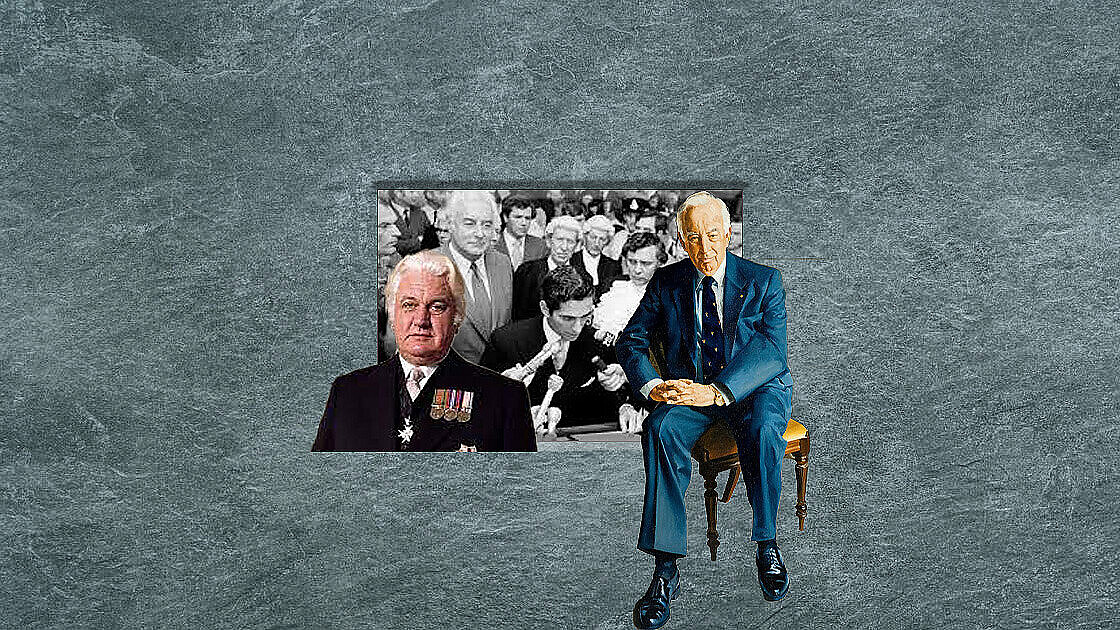

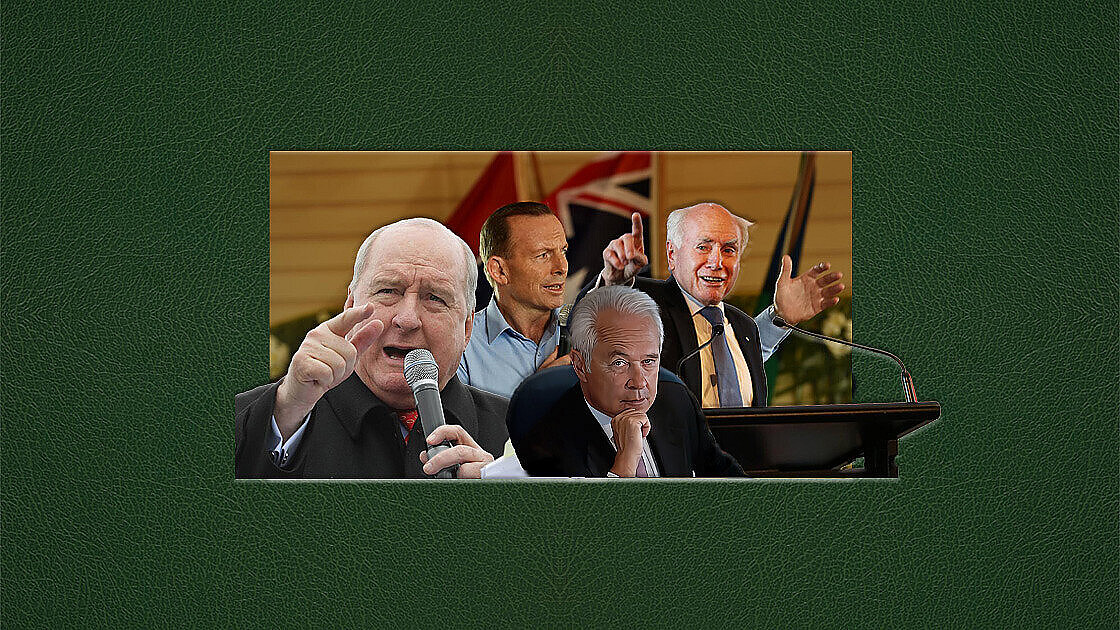

But to the extent that the exercise of the reserve power is controversial, could this imperil their future exercise? In other words, are they in the nature of a wasting asset? Lord Byng’s refusal of a request for dissolution of the Canadian House of Commons in 1926 was controversial, but this pales in comparison with Sir John Kerr’s termination of Prime Minister Whitlam’s commission in 1975. Sir David Smith has demonstrated, beyond serious argument, that the withdrawal was a proper exercise of the reserve power, an action strongly and regularly advocated by Mr Whitlam himself while in opposition. Indeed in 1975, Sir Garfield Barwick, the then Chief of Australia, went so far as to advise that more than a discretion, the Crown has a positive obligation not to retain Ministers who could not produce supply.

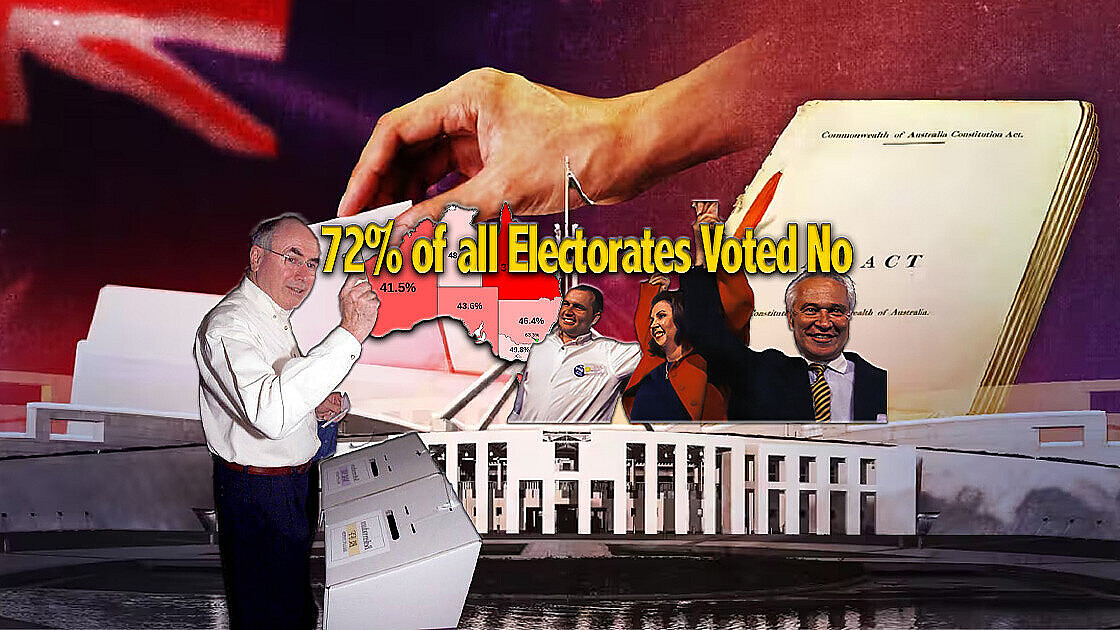

In this context, it should be recalled that republicanism only came onto the serious political agenda in Australia because of the conjunction of two phenomena. First, we had the interpretation that the politicians and media were prepared to advance about the dismissal, and second, the strong antipathy Prime Minister Paul Keating displayed towards the monarchy. As to the interpretation of the dismissal, not only the dismissed prime minister but also the principal political beneficiaries of the event, sooner or later, joined in the extraordinary action of actually attributing blame to the constitutional monarchy for their very own actions. In relation to the beneficiaries, this was even more extraordinary as the action taken, the dismissal of the prime minister was precisely the action which they had asked, and at times insisted, the governor-general take. While their behaviour is consistent with the modern trend of seeking some way of divesting themselves of any personal responsibility for those actions, which one may regret, it can only strengthen the disdain the community has concerning their elected representatives. In any event, all the leaders of the political parties in the House of Representatives at the time, the Honourable Edward Gough Whitlam, the Right Honourable Malcolm Fraser and the Right Honourable Doug Anthony, campaigned vigorously in favour of the republic proposed in the 1999 referendum. (More recently, the former premier of New South Wales, Mr Bob Carr, referring to Mr Whitlam’s dismissal, went so far as to declare that the reserve powers do not exist. He admitted that his decision to expel the governors of New South Wales from Government House in1996 was to demonstrate to them that they were no more than ceremonial rubber stamps. )

In this re-interpretation of the dismissal, the politicians have been assisted by an agenda-driven media. As Lord Deedes, the former editor of the London Daily Telegraph, wrote of the 1999 referendum, he had rarely attended elections in any democratic country where the press had displayed “more shameless bias”.

Given this demonstrated propensity of the political and media establishment to come together to change historical facts found to be inconvenient, in this case, to shift the blame for their own acts to the Crown, it is little wonder that one constitutional scholar has asked whether the Crown could easily absorb another such crisis, “however justifiable the Governor’s decisions might be from a purely legal point of view”.

This is in no way to deny the importance of the reserve powers, particularly the power to withdraw the commission of an errant prime minister. It would be an exaggeration to draw an analogy between the cold war nuclear deterrent and the phenomenon of mutually assured destruction. But the likelihood of mischief in its portrayal of any exercise by the political class must disturb constitutionalists, whether they want to change or not.

The crisis in 1975, which Sir David Smith rightly categorises as a political and not a constitutional crisis, was the product of two politicians unwilling to compromise. It should be recalled that Mr Whitlam, in opposition, had asserted that any prime minister who refused supply by the Senate should resign. Had he done in 1975 what he had preached consistently in his years in opposition, there would have been no crisis. And had Mr Fraser waited until the next election, he would have enjoyed a victory untainted by accusations that he had behaved shamefully.

Perhaps there is a solution which is consistent with the Westminster system. Such a solution might lie in allowing a recall election. This is typically a three-stage process, with the final two stages taken simultaneously. The first stage is a petition signed within a prescribed time by a minimum percentage of electors, say, 10 or 12%. This is followed by a vote open to all electors to determine whether an election should be held. For convenience, a ballot for the election is held at the same time, although this could subsequently be found to have been unnecessary.

The recall election has been adapted to a Westminster parliamentary system, that of the Canadian province of British Columbia. In practice, successful recall elections are rare, but it is arguable that if this mechanism had been available in Australia in 1975, the opposition would have concentrated on investigating its availability rather than in refusing supply. The legitimacy of its use, successful or not, would be difficult to challenge. This is in no way a proposal to remove, amend, modify or reduce the reserve power to withdraw the prime minister’s or premier’s commission. This power would still exist and would remain available for use against an errant head prime minister or premier.

The attraction of the recall election is that it is not inconsistent with the Burkian concept that democracy under the Westminster system is not direct but representative. Edmund Burke expressed this principle succinctly:

“Your representative owes you not his industry only but his judgement, and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices your opinion.”

This proposal for a provision for recall elections may thus be distinguished from other proposals for direct democracy and which involve initiatives by the citizenry, usually known as CIR’s Citizen Initiated Referenda. As these are intended to have a direct legislative effect, they involve an exception to the Burkian principle.

Interesting Links

An Historical Perspective On The Reserve Powers, by JB Paul 21 August 1999

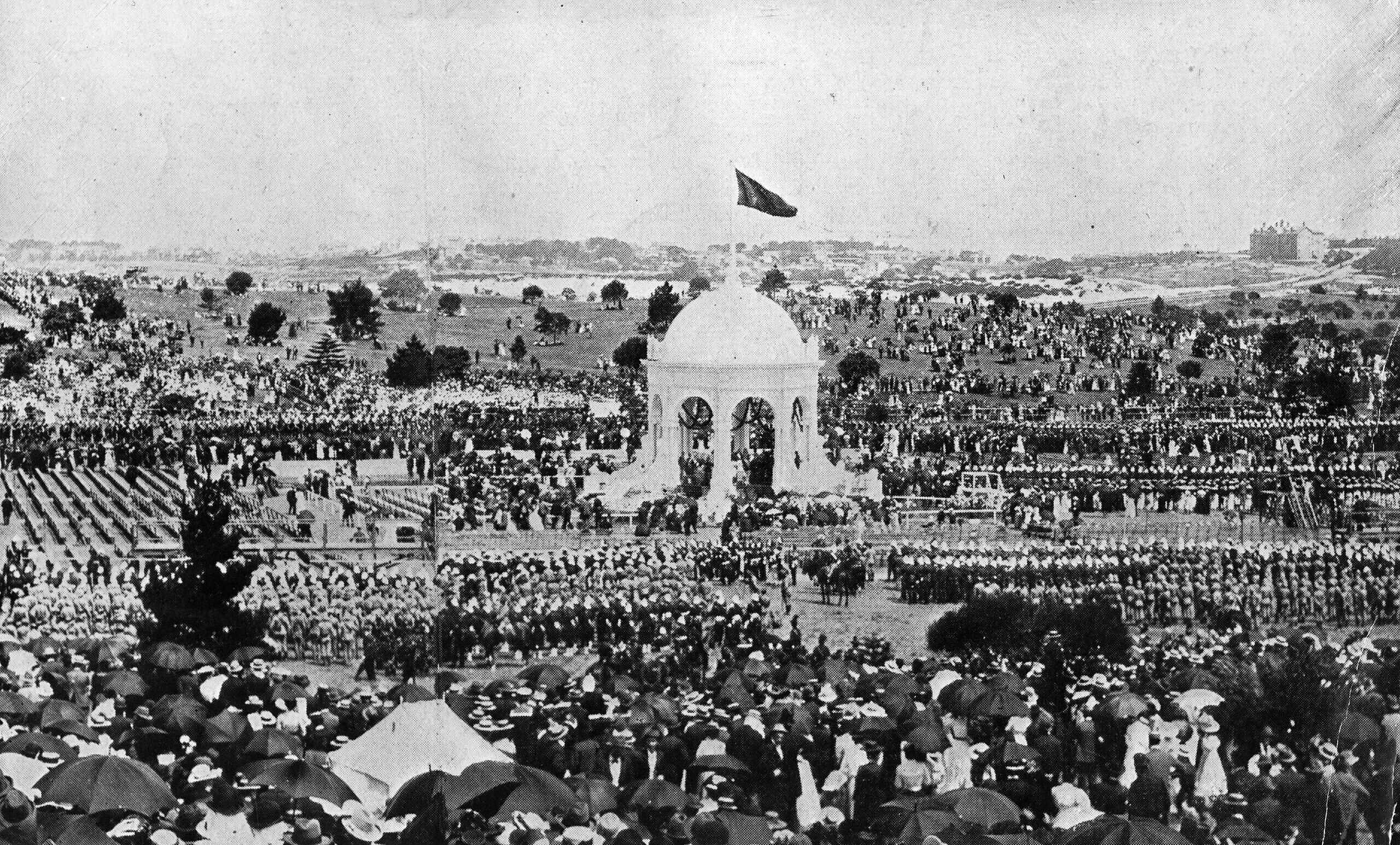

Examples Of The Use Of Vice-Regal Power In Australia Since Federation