Charles III acceded to the throne of the United Kingdom and the thrones of the other Commonwealth realms upon the death of his mother, Elizabeth II, on the afternoon of 8 September 2022. Royal succession in the realms occurs immediately upon the death of the reigning monarch. The formal proclamation in Britain occurred on 10 September 2022, at 10:00 BST, the same day on which the Accession Council gathered at St James's Palace in London.[1][2] The other realms, including most Canadian provinces and all Australian states, issued their own proclamations at times relative to their time zones, following meetings of the relevant privy or executive councils. While the line of succession is identical in all the Commonwealth realms, the royal title as proclaimed is not the same in all of them.

Australia

The proclamation in Australia took place in front of the Parliament House, Canberra, on 11 September and was read out by Governor-General David Hurley after being approved by an Australian Executive Council meeting at the Government House. The proclamation was signed by Hurley and countersigned by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. An Indigenous Australian dance ceremony followed the proclamation along with a 21-gun salute.[97][98][99][100][101] Similar proclamations took place on the same day in all the states of Australia, except Victoria, which issued its proclamation on Monday, 12 September, reflecting each state's separate relationship to the crown.

Text of proclamation

The proclamation was read by Governor-General David Hurley at Parliament House.[102]

Whereas because of the death of our blessed and glorious Queen Elizabeth II, the Crown has solely and rightfully come to Prince Charles Philip Arthur George.

We, therefore, General the Honourable David Hurley AC DSC (Retd), Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, and members of the Federal Executive Council, do now proclaim Prince Charles Philip Arthur George to be King Charles III, By the Grace of God, King of Australia and his other realms and territories, Head of the Commonwealth, and with hearty and humble affection, we promise him faith and obedience. May King Charles III have long and happy years to reign over us.

Given at Canberra, this 11th day of September 2022, and in the first year of His Majesty's reign.

Signed by me, as Governor-General and counter-signed by my command, by the Honourable Anthony Albanese MP, Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia.

God Save the King

State proclamations

New South Wales

The proclamation ceremony in New South Wales took place on the steps of the New South Wales Parliament House, Sydney, on 11 September[103] and was read out by Governor Margaret Beazley. The ceremony was followed by a 21-gun salute from the grounds of the Government House. Public transport was made free for the day of the ceremony.[104] The New South Wales Police Force estimated that approximately 5,000 had attended the ceremony.[105]

The proclamation occurred after a meeting of the New South Wales Executive Council earlier that day, which was presided by the state Governor Margaret Beazley at the Government House. In the meeting, state premier Dominic Perrottet and other state ministers recommended that the Governor proclaim Charles III as King of Australia, which the Governor accepted.[103][106]

WHEREAS because of the death of our blessed and glorious Queen Elizabeth the Second, the Crown has solely and rightfully come to Prince Charles Philip Arthur George:

We, therefore, Her Excellency the Honourable Margaret Beazley AC KC, Governor of the State of New South Wales in the Commonwealth of Australia, and members of the Executive Council, do now proclaim Prince Charles Philip Arthur George to be King Charles the Third, by the Grace of God King of Australia and his other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth, and, with hearty and humble affection, we promise him faith and obedience: May King Charles the Third have long and happy years to reign over us.

Given at Sydney, this eleventh day of September, Two thousand and twenty-two, and in the first year of His Majesty’s reign.

GOD SAVE THE KING!

Queensland

The proclamation in Queensland was held first at the Government House and later at the Parliament House in Brisbane on 11 September. It was read out by Governor Jeannette Young.[107] Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk attended both of the ceremonies and delivered a tribute to Queen Elizabeth II. An estimated 2,300 Queenslanders attended the ceremony at the Government House, according to the state government.[108][109]

WHEREAS because of the death of our blessed and glorious Queen Elizabeth the Second, the Crown has solely and rightfully come to Prince Charles Philip Arthur George:

We, therefore, DR JEANNETTE ROSITA YOUNG AC PSM, Governor of Queensland and its dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia, and members of the Queensland Executive Council, do now proclaim Prince Charles Philip Arthur George to be King Charles the Third, by the Grace of God King of Australia and his other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth, and, with hearty and humble affection, we promise him faith and obedience:

May King Charles the Third have long and happy years to reign over us.

Given at Brisbane this eleventh day of September, two thousand and twenty-two, and in the first year of His Majesty's reign.

South Australia

The proclamation in South Australia took place outside the South Australian Parliament House in Adelaide on 11 September and was read by Governor Frances Adamson. The ceremony was attended by Premier Peter Malinauskas, Speaker of the House of Assembly Dan Cregan, President of the Legislative Council Terry Stephens, and other officials. An estimated 8,000 South Australians gathered to witness it.[110][111][112]

WHEREAS because of the death of our blessed and glorious Queen Elizabeth the Second, the Crown has solely and rightfully come to Prince Charles Philip Arthur George:

We, therefore, Her Excellency the Honourable Frances Jennifer Adamson, Companion of the Order of Australia, Governor in and over the State of South Australia, and members of the Executive Council, do now proclaim Prince Charles Philip Arthur George to be King Charles the Third, by the Grace of God King of Australia and his other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth, and, with hearty and humble affection, we promise him faith and obedience:

May King Charles the Third have long and happy years to reign over us. Given at Adelaide this eleventh day of September, Two thousand and twenty-two, and in the first year of His Majesty’s reign.

Tasmania

The proclamation in Tasmania took place at the Government House in Hobart on 11 September. The text was read out and signed by Governor Barbara Baker and Premier Jeremy Rockliff. Anglican Bishop of Tasmania Richard Condie later read the Collect for the Monarch from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.[113][114][115]

WHEREAS because of the death of our blessed and glorious Queen Elizabeth the Second, the Crown has solely and rightfully come to Prince Charles Philip Arthur George:

We, therefore, Her Excellency THE HONOURABLE BARBARA BAKER AC, Governor of Tasmania, and members of the Executive Council, do now proclaim Prince Charles Philip Arthur George to be King Charles the Third, by the Grace of God King of Australia and his other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth, and, with hearty and humble affection, we promise him faith and obedience:

May King Charles the Third have long and happy years to reign over us.

Given at Hobart this eleventh day of September, Two thousand and twenty-two, and in the first year of His Majesty's reign.

Victoria

The proclamation in Victoria took place at the Government House in Melbourne on 12 September and was read out by Governor Linda Dessau, who re-swore Lieutenant-Governor James Angus and acting Supreme Court chief justice Karin Emerton to their posts under a constitutional requirement. The ceremony was also attended by Premier Daniel Andrews and Opposition Leader Matthew Guy.[116]

The proclamation was jointly signed by Dassau, Andrews, Emerton, Legislative Assembly speaker Maree Edwards and the President of the Legislative Council, Nazih Elasmar.[117][118]

On 13 September, Edwards read out the proclamation in the Parliament of Victoria, following which all Legislative Assembly MPs were asked to swear their allegiance to King Charles. Samantha Ratnam, the leader of the Victorian Greens party, criticised this policy as absurd.[119]

We, the undersigned, do hereby proclaim our late Sovereign Queen Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God, Queen of Australia and Her other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth, is deceased and that by the death of our late sovereign, the Crown has solely and rightfully come to His Royal Highness Prince Charles Philip Arthur George, Prince of Wales, Knight of the Order of Australia who is now His Majesty King Charles the Third, by the Grace of God, King of Australia and His other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth. God save the King!

Given at Melbourne this 12th day of September in the Year of our Lord Two thousand and twenty-two and in the first year of the reign of His Majesty King Charles the Third.

Western Australia

The proclamation in Western Australia took place at the Government House in Perth on 11 September and was read out by Governor Chris Dawson. It was signed by Premier Mark McGowan and Dawson.[120][121]

Whereas because of the death of our blessed and glorious Queen Elizabeth the Second, the Crown has solely and rightfully come to Prince Charles Philip Arthur George:

We, therefore, His Excellency the Honourable Christopher John Dawson APM, Governor of the State of Western Australia, and members of the Executive Council do proclaim Prince Charles Philip Arthur George to be King Charles the Third, by the Grace of God King Australia and his other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth, and, with hearty and humble affection, we promise him faith and obedience:

May King Charles the Third have long and happy years to reign over us.

Given at Perth this eleventh day of September 2022 and in the first year of His Majesty’s reign.

Australia has a superb constitutional system. At the centre of our federal parliamentary democracy, we have an institution above politics which acts as a check and balance on the political branches: the Australian Crown.

According to the High Court, The Queen is the Sovereign, the Governor-General is the constitutional head of the Commonwealth, and the Governors are the constitutional heads of state.

The Sovereign ( The Queen or The King) is at the very centre of our constitutional system. In Queen Elizabeth II, we have been blessed with a Sovereign whose performance has been impeccable. Even those who wish to remove the Australian Crown from our constitutional system respect her greatly. So many Republicans say they now have to wait until this reign ends. They did not think this at the referendum in 1999.

The role of the Sovereign is not, however, dependent on the qualities of the present incumbent, Queen Elizabeth II. The Sovereign is, at one and the same time, the person wearing the Crown and the office itself. This is illustrated by the traditional announcement on the passing of the Sovereign, “ The King is Dead. Long Live The King!”

The concept that the Sovereign is both a person and an office has long been referred to as “The King’s Two Bodies,” a concept discussed below

The question of who is the Sovereign is determined according to Australian law relating to succession. This law is identical throughout the sixteen Realms in the Commonwealth of Nations. Under section 61 of the Australian Constitution, the executive powers of the Commonwealth are vested in the Australian Crown and are exercisable by the Governor-General.

The Queen appoints and may remove the Governor-General and the State Governors on ministerial advice and, on special occasions, undertake activities outside of the country as requested. When Her Majesty is in Australia, she may undertake such roles normally performed by the Governor-General and the Governors as advised.

Over the years, the Crown has been Australianised. The Australian Crown is not just an appendage but at the core of our heritage. Some people ask them why we could not dispense with The Queen. They ask whether we could have Governors-General and Governors without a Sovereign. Before the removal of the Crown is even proposed, proponents should understand the Crown, which has ten essential aspects.

The following pages deal with these topics:

Queen Elizabeth II

It is sometimes said, based perhaps on Matthew, that by their words shall ye know them. The words of our Sovereign describe exactly her mission in life, a mission to which she has remained faithful. What is surprising is that it is only now that many in the media and in politics have come to understand that The Queen means what she says. And unlike many in modern political life, The Queen believes that an oath sworn on the Bible is important and should be honoured. She had always kept to the promises she made when she came of age and was crowned and anointed. She became Queen of Australia - and Her fifteen other Realms on the death of her father, King George VI, what is called the Accession. This was on the 6th of February 1952 while she was in Kenya with Prince Phillip on their way to Australia and New Zealand.

The Queen was crowned on 2 June 1953 in an ancient ceremony full of meaning. Wearing a gown embroidered with the floral emblems of the nations of the Commonwealth, including wattle from Australia, she swore to uphold our laws.

The Archbishop of Canterbury: "Will you solemnly promise and swear to govern the Peoples of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia , New Zealand , the Union of South Africa, Pakistan and Ceylon and of your Possessions and other Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, according to their respective laws and customs?"

The Queen: "I solemnly promise so to do."

The Archbishop of Canterbury: "Will you to your power cause Law and Justice, in Mercy, to be executed in all your judgments?"

The Queen: "I will."

The Archbishop of Canterbury: "Will you, to the utmost of your power, maintain the Laws of God and the true profession of the Gospel? Will you to the utmost of your power maintain in the United Kingdom the Protestant Reformed Religion established by law? Will you maintain and preserve inviolable the settlement of the Church of England, and the doctrine, worship, discipline, and government thereof, as by law established in England? And will you preserve unto the Bishops and Clergy of England, and to the Churches there committed to their charge, all such rights and privileges, as by law do or shall appertain to them or any of them?"

The Queen: "All this I promise to do. The things which I have here before promised, I will perform, and keep. So help me God."[

Once the taking of the oath concludes, an ecclesiastic presented a Bible to The Queen, saying, "Here is Wisdom; This is the royal Law; These are the lively Oracles of God."

By swearing an oath on the Bible, a person stresses his or her commitment before God to keep the promise. When we are called to give evidence in court, we promise to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth. ( Other arrangements of equal significance are made for those of other religions. Those who have no religion make an affirmation.)

The Queen is strongly committed to the Oath she made at her coronation. Therefore, retirement or, more correctly, an abdication merely because of age was always out of the question and never contemplated - except in media speculation.

On her 21st birthday, The Queen indicated how she intended to fulfil her role in life:

“I declare before you all that my whole life, whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service and the service of our great imperial family to which we all belong.”

More recently, she gave an indication of her strong faith when she said:

“For me, the teachings of Christ and my own personal accountability before God provide a framework in which I try to lead my life. Like so many of you, I have drawn great comfort in difficult times from Christ's words and example. I believe that the Christian message, in the words of a familiar blessing, remains profoundly important to us all: "Go forth into the world in peace, be of good courage, hold fast that which is good, render to no man evil for evil, strengthen the faint-hearted, support the weak, help the afflicted, honour all men… It is a simple message of compassion… and yet as powerful as ever today, two thousand years after Christ's birth.”

And again, after 9/11, she told the American people:

“Grief is the price we pay for love.”

The Queen, who has reigned over us for more than one-half of the life of the Commonwealth of Australia, attracts, and rightly attracts, the admiration of the people of Australia. The reaction in Melbourne at the Opening Ceremony of the Commonwealth Games, when the 80,000 or so present joined with Dame Kiri Te Kanawa in singing not only Happy Birthday but in standing to sing the few bars of the Royal Anthem the censorious organizers permitted, is testimony to that. According to the former Republican leader, the Hon.Malcolm Turnbull, another referendum:

“… should not be put up for another vote unless there is a strong sense in the community that this is an issue to be addressed NOW…In addition, in order to be successful a republic referendum needs to have overwhelming support in the community, bipartisan support politically and, in truth, face modest opposition. A republic referendum should not be attempted again unless the prospects of success are very, very high…… I do struggle to see how a republic referendum could get the level of support it needs to win during the reign of the present Queen.”

We have been blessed with a Sovereign who has never put a foot wrong, has never embarrassed us, does her duty, and for whom we do not pay and never will pay. In brief, her service has been impeccable. The Queen is now revered as she was when she first came to Australia.

And yet, it is a little appreciated fact that the Crown, the oldest institution in the nation, remains central to and permeates our constitutional system, which is one of the world’s most successful. Nevertheless, the place of the Crown and, therefore, The Queen in our constitutional system remains under challenge, but certainly not to the degree the republican media claim and indeed crave.

The King’s Two Bodies

The Sovereign is at the very centre of our constitutional system. Those great Commonwealth constitutional authorities, the Canadian Dr Eugene Forsey and the Australian Dr.H.V. Evatt, long ago conclusively demonstrated the important and crucial role of the Sovereign’s representative as a constitutional guardian. This is but one aspect of the monarchy.

The organizing principle of government in Australia, and in the other fifteen Commonwealth Realms, is monarchical. As in Canada, so in Australia, its pervasive influence has moulded and influenced her courts, her laws, her parliaments, her executives at both levels of government, state or provincial, and federal, her armed forces, her diplomacy and her public or civil services. Sir Robert Menzies put it succinctly: “the Crown remains the centre of our democracy.”

The Sovereign is, at one and the same time, both a natural person and the office itself. This might have had its roots in classical antiquity. This is expressed in the ancient maxims Dignitas non moritur, or Le Roi ne meurt jamais, and in the exclamation on the demise of the Crown, Le Roi est mort. Vive Le Roi! (The King is Dead. Long Live The King!) The consequence is that immediately on the demise of the Crown, in the twinkling of an eye, the successor becomes the Sovereign, and the Crown continues without any interregnum.

So, under our ancient law, the Sovereign has not one, but two bodies. The Sovereign has both a natural body and a body politic. We understand something of this in other places. There is a minister for this or that, and the office continues whoever fills it. There is a bishop of such and such, and the bishopric continues after the incumbent goes. It is even more so with the Sovereign, who will reign for life except in the most exceptional circumstances. The Sovereign is both a natural person, but he or she is also the office. The important point is that there cannot be a break. There cannot be an interregnum: the clearest example is in the reign of Charles II, beginning immediately after the death of Charles1.

An interregnum in other ages would have been far too dangerous. It could have led to doubt, uncertainty and instability on the demise of the Crown. It might even have led to insurrection and civil war. So, the succession has to be immediate, and the successor has to be known, either presumptive or apparent. Accordingly, the acclamation on the demise of the Crown is: “The King is Dead. Long Live the King!”

The doctrine of the King’s two bodies is an ancient principle, well expressed in Calvin’s Case in 1608:

“For the King has in him two Bodies, viz., a Body natural and a Body politic. His body natural…is a Body mortal, subject to all Infirmities that come by Nature or Accident, to the imbecility of infancy or old Age, and to the like defects that happen to the natural Bodies of other People.

“But his body politic is a Body that cannot be seen or handled , consisting of Policy and Government, and constituted for the Direction of the People and the Management of the publicWeal, and this body is utterly devoid of Infancy, and Old Age, and the other Defects and Imbecilitities, which the Natural Body is subject to, and for this Cause, what the King does in his Body politic, cannot be invalidated or frustrated by any Disability in his natural Body”.

This is central to our constitutional law. It is perhaps more easily understood today if we refer to the King’s body politic as the Crown.

We find this usage in the Preamble to the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, 1900 (Imp.). This was the act of the Imperial or British Parliament, which formally constituted the Commonwealth of Australia. The Preamble recites that:

“Whereas the people of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland, and Tasmania, humbly relying on the blessing of Almighty God, have agreed to unite in one indissoluble Federal Commonwealth under the Crown of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and under the Constitution hereby established:” ( Note, incidentally, that the Crown here is a description of the then indivisible Imperial Crown, which has since divided into the separate Crowns of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the other Realms.)

The use of the Crown to describe the Sovereign’s body politic was, as Maitland says, of relatively recent use at the time of the Federation. While the word “Crown” is used in the Preamble, the Constitution uses the word “Queen”. But the many references to the “Queen”, while referring at that time to Queen Victoria, also refer to her body politic. This is confirmed by the terms of section 2 of the Constitution Act, which provides that the provisions of the Act “referring to the Queen shall extend to Her Majesty's heirs and successors….”

Once it is understood that the references in the Constitution to the Queen include a reference to the King or Queen in his or her body politic, that is, the Crown, and that this is now the Australian Crown, much of the mischief which has been made about that document evaporates. For example, if we take the key sections, sections 2 and section 61, and read them using more current terms and in light of the latest constitutional developments, the intention becomes crystal clear:

2. A Governor-General appointed by the Sovereign shall represent the Australian Crown in the Commonwealth….

61. The executive power of the Commonwealth is vested in the Australian Crown and exercisable by the Governor-General. The executive power extends to the execution and maintenance of this Constitution and of the laws of the Commonwealth.

(This is not a suggestion for any constitutional amendment. It would be foolish to amend a constitution to take into account transient fashions and partisan arguments in a referendum campaign. This is merely an explanation of the meaning of those sections.)

The conclusion is that the many references in the Constitution to The Queen are references to the Sovereign in his or her body politic, which today we would refer to as the Australian Crown. It is important to understand that the Crown is more than the office of the Governor-General and the offices of the Governors, or indeed the sum of them. It is an ancient but evolved Leviathan which permeates not only the Constitution in the narrow sense –the federal Constitution but also those of the states. And it extends to the broader constitutional system under which we are governed.

There is a need to understand that the governor-general is the representative of The Queen’s body politic, that is, the Crown, and is not limited to Australia.

As long ago as 1945, the private secretary to the Canadian Governor-General, Shuldham Redfern, observed: “It is often said the Governor-General is the personal representative of the King. It would be more correct to say that he is the official representative of the Crown, for there is a difference between representing a person and representing an office held by a person.”

This conclusion is understandable, given the phenomenon that the Canadian authority, Professor David E Smith, refers to as the separation of the person of the monarch from the concept of the Crown in Canada. This not only involves the absence of the monarch and her court but also the more recent policy of the Canadianisation of the Crown.

This conclusion may go further than is necessary. It is one thing, and a correct thing too, to emphasise that a governor-general is the representative of the Crown. But it is not “more correct” to say so. While it is clearer to modern ears, that does not make it “more correct.” Indeed, it would be incorrect to deny or underplay the fact that the governor-general is, constitutionally, as much the personal representative of the Sovereign as of the Crown. While we can distinguish the Crown from the person of the Sovereign, we can never divorce them. Not even a demise of the Crown or an abdication can do that.

Not only can we not have the Crown without the Sovereign, but we also cannot retain some sort of facsimile of the Crown if we remove the Sovereign from our Constitution. This is the fundamental flaw of Republican minimalism, a fact which seems to elude both the Republican movement and the Republican commentariat.

This is why the many proposals for change to some form of a republic hitherto have all failed at the threshold. As Canadian Professor David E. Smith observes, in any Canadian republic, some alternative concept would have to fill the void of the absent Crown, and none of the proposals attempts this.

The most facile republican model in Australia has been the celebrated and perhaps notorious “tippex” solution advanced by the Australian Republican Movement and the Keating government. The proponents argued that Australia could be converted into a republic by the simple act of whitening out the words "Queen", "Crown", and "Governor-General" and replacing them all with the word "President". But as Justice Lloyd Waddy pointed out, this is an attempt to overthrow of the entire theoretical basis of the law and practice of the Constitution, which “… is, to put it mildly, somewhat more complex.”

As seen from Canada, the case for substantial constitutional change advanced in recent years in Australia seemed surprising to be based on one simple desideratum: to get rid of The Queen. Professor David E. Smith asks the obvious question: “Why such an unsophisticated rejection?” The extreme narrowness of the Australian republican raison d'être has been largely ignored in the media, in political circles, and in the academy. Yet the consequences to the constitutional fabric of the nation would be momentous.

Although the “tippex” solution has been formally abandoned, the Republican movement has advanced a little further from this simplistic approach. Indeed, the official position of the Republican movement since the referendum is curious. It is that they now have no Republican model. Yet they still demand what the Republican leader and author, Mr Thomas Keneally, correctly indicated would be “the biggest structural change to the Constitution since Federation.” It is indeed unusual, to say the least, to demand change of such enormity but then to admit that the proponents of change, including a Senate committee, admit to having absolutely no idea of what change is envisaged.

This refusal to admit to a model may well be a tactic to paper over significant differences among Republicans and to encourage endorsement of the Republican movement’s campaign for a cascading series of plebiscites and a referendum at the federal and presumably at the state levels. A leading Republican politician, Senator Marise Payne, who originally endorsed this process, changed her position significantly in a senate committee report after Professor Greg Craven had persuaded her that this would necessarily lead to the model in which the president is directly elected. As a result, Senator Payne asks that the proposal for a second federal plebiscite be abandoned but that the first federal plebiscite be retained.

Whether or not this further division between the Republican politicians is resolved, the demand for major change, without specifying that change, is not only curious, it is worse. What is being demanded is that the Australian people cast a vote of no confidence in one of the world’s most successful constitutions without knowing what, if anything, is to fill the vacuum.

It is difficult to imagine a more irresponsible proposal.

The flaw in all this involves a refusal to countenance the existence of that vast institution at the heart of the constitutional system, the Crown. Hitherto, all significant proposals for republican change have been based on this denial and involve an attempt to graft a republic onto an intrinsically monarchical constitutional system. I refer to the broader constitutional system, of which the Australian Federal Constitution is but a part.

The point is that in the way it was drafted, in the way in which it was approved, and in the way in which it has allowed Australia to develop and play a significant role in the world in the defence of freedom, the Australian Constitution must be counted among the world’s most successful. Nevertheless, change to a particular republican model is possible if that were the considered wish of the Australian people. What is not possible is a change to “a” republic. The Constitution, wisely, in my view, does not permit this vagueness. Those who say they are Republican but have no idea of the sort of republic they want have just not taken the first essential step in the debate - determining precisely what is to be changed and why.

Such is the poverty of republican theory that comfort is sought in the presumption that a republic is inevitable. Note that this is an undefined republic. What is being predicted is that the Australian people will abandon their highly successful Constitution in return for “a” republic, that is, any republic. A perusal of the referendum campaigns before and since the foundation of the nation indicates that, as Hon. Richard McGarvie used to say, Australians are “wise constitutional people.” And as we are famously informed, the only things inevitable are death and taxes. Those of age will recall a view proclaimed by many, including those who did not wish it to be so, that some form of socialism was inevitable - if not Stalinism, then at least that brand of socialism that required that the commanding heights of the economy be publicly owned or controlled. Those who propose a socialist future are now a small minority, and even fewer would say today that socialism is inevitable.

Australianising The Crown

While Canadianisation of the Crown became a formal government policy under the Trudeau government, Australianisation has been a piecemeal process. Indeed, the Australian Constitution had, from its adoption, and almost unnoticed, made a significant step towards Australianisation. This was done by a measure unprecedented in the Empire – the placing of the exercise of the executive power of the Commonwealth in the hands of the governor-general. Another unprecedented measure was to grant the new Commonwealth of Australia the power to change its own Constitution.

In any event, the trend over the years has been to move further down the path of Australianising the Crown, vesting more authority and status in the governor-general but still as representative of the Crown. An important measure has been to declare to foreign governments and international organizations that the governor-general is the head of state and should be accorded that dignity.

If Australianisation means that the governor-general may do things in Australia and beyond the seas which are consistent with his or her role of representing and exercising the powers of the Australian Crown, there can surely be no objection. This is, after all, consistent with the formula in the Balfour Declaration made in the early part of the twentieth century:

“…it is an essential consequence of the equality of status existing among the members of the British Commonwealth of Nations that the Governor-General of a Dominion is the representative of the Crown, holding in all essential respects the same position in relation to the administration of public affairs in the Dominion as is held by His Majesty the King in Great Britain, and that he is not the representative or agent of His Majesty’s Government in Great Britain or of any Department of that Government.”

But this does not mean the office should take on a character different from and inconsistent with the Crown in a constitutional monarchy. We are becoming accustomed to hearing on the announcement of an appointment to a vice-regal office that the incumbent will, once in office, concentrate on some or other worthy cause. Too often, this is dangerously close to a political agenda, however worthy. This is not an appropriate vice-regal vocation: that vocation is to represent the Crown, to provide leadership beyond politics. How can they provide this if their agenda is even tangentially political? The vice regal-elect should first acquaint themselves with the office before announcing some or other agenda.

A former Governor-General, Sir William Deane, devoted much of his term to the advancement of the interests of Australia’s indigenous people. At most times, it was possible to conclude that this interest had not become political, that he was in no way challenging government policy, but that he was engaged in taking a well-intended interest in the indigenous people. On one occasion, he was criticised by a national newspaper for arranging direct access to The Queen without referring the request to the government. But after he left office, Sir William became openly critical of government policy, sometimes harshly so. The unfortunate result was that, retrospectively, he confirmed in the minds of many that he had crossed the line while in office. This experience justifies the proposition that even after he or she leaves office, a governor-general should be careful never to compromise the office. Speaking in favour of a republic, or even opining that it is inevitable, seems inappropriate for one who has represented the Crown. But to do so in office is, at the very least, a most inappropriate entry into politics, apart from being an act of disloyalty to the Sovereign to whom the viceroy has sworn allegiance.

In Canada, in order to overcome what he saw as public indifference to the office of the governor-general, a former incumbent suggested that the governor-general henceforth have greater freedom to express his personal ideas and even that he be made chairman of a new senate. Another suggestion was that the governor-general, outside of the extraordinary circumstances referred to above, should be able to refuse assent to legislation.

Apart from a governor-general being free to speak on matters clearly, not on the political agenda, all of these proposals are inconsistent with the concept of constitutional monarchy. They may well flow from the mistake of consciously or subconsciously seeing the office as separate and autonomous from the Crown. This is not an office that can have no existence apart from and independent of the Crown.

A viceroy is the representative of the Crown, nothing less – and nothing more. Walter Bagehot observed: “We must not bring The Queen into the combat of politics or she will cease to be reverenced by all combatants; she will become one combatant among

many.” Obviously, this advice applies equally to a viceroy.

Our Heritage

The Crown, our oldest institution, is thus at the very centre of our constitutional system, linking us to the other Realms and to the Commonwealth of Nations. It is part of the heritage handed down to us by the British, including the rule of law, the common law, our Judeo–Christian values, and responsible government under the Westminster system. This heritage allowed Australia to be the success story of the twentieth century. This may offend the cultural relativists, but it is established that colonisation by the British, compared with that of other powers, has usually been of considerable advantage to the colonised. According to a study by researchers from Harvard and the University of Chicago, former British colonies rank among some of the world’s best administrations. Of the top ten, five were based on the common law, which strongly defends property and individual rights. Apart from Switzerland, there were four Scandinavian countries whose constitutional systems were influenced by Britain.

Constitutional monarchies, through their structure, avoid those four republican perils: excessive rigidity, as in the American system, which is reduced to near paralysis whenever the President is seriously threatened with impeachment; political conflict and competition between the head of state, prime minister and ministers, a hallmark of the French Fifth Republic, an inherently unstable model curiously followed in a number of countries; extreme instability, which often haunted the Latin versions of Westminster and regular resort to the rule of the street to solve the conflict, which permeates those systems which live under the shadow of the French revolution.

Another measure of relevance is the UN Human Development Index (HDI). This is a comparative measure of poverty, literacy, education, life expectancy, childbirth, and other factors in most of the countries of the world. It is a standard means of measuring well-being, especially child welfare. The HDI is contained in a Human Development Report, which is published annually. Every year, constitutional monarchies make up most or all of the leading five countries and a disproportionate number of the leading ten, fifteen, twenty, and thirty countries. No constitutional monarchy comes into the corresponding lists at the other end. The results are so consistent that dismissing this as a mere coincidence would be difficult. This corroborates the results of the research at Harvard and Chicago.

These matters are not, of course, conclusive against fundamental constitutional change in Australia. They do support the contention that those who would change are under a duty not to hide or ignore the Crown, but as a first step, to understand its role and function in our constitutional system. The behaviour of politicians who attempt to hide or suppress the symbols of the Crown is, at best, ignorant and ideologically driven, occasionally spiteful and at worst, sinisterly indicative of a wish to remove these checks and balances on their exercise of power, as we have seen in relation to the eviction of the governors from Government House in New South Wales.

Once those who propose change demonstrate an understanding of the role and function of the Crown, they are then under a duty to the Australian nation to develop sound reasons for change and, most importantly, to develop a model which is, in all respects, as sound as the constitutional system which has ensured the extraordinary success that is the Commonwealth of Australia. To seek change without understanding and change without knowing what that change should be is consistent with a view that the electorate is naïve, easily manipulated and gullible. It was precisely against such a campaign that the founders devised the procedure for change by way of a referendum under section 128 of the Constitution.

Governor-General and Governors Without a Sovereign

While accepting the Crown's considerable, indeed central role in our history and our constitutional system, it is sometimes argued that we could retain all the benefits of the Crown while dispensing with the Sovereign. Many, if not most, of the forms of republics proposed at the 1998 Constitutional Convention and since then purport to do this. This is particularly true of the minimalist models, which may even go so far as to retain the name of Governor-General. One model proposes that the role of appointing and dismissing the viceroys be the responsibility of a council of eminent persons acting on political advice instead of the Sovereign.

The proposition that the Crown could effectively be retained without keeping the Sovereign is completely fallacious. This is not merely because we would lose the impeccable standards set by Queen Elizabeth II; however, we are fortunate to have known these during her reign, which, incidentally, has extended over more than one-half of the life of our Commonwealth.

Her Majesty’s dedication, personal standards and sense of judgement are celebrated, and rightly so. Indeed, a viceroy in a quandary as to what behaviour would be appropriate could do no better than ask himself or herself:

“What would The Queen do in a case like this?”

The fundamental, unavoidable and insoluble problem for such republican models is that without The Queen, there can be no Crown. Not only would the offices of the viceroys who are above politics disappear, but so would the fountain of honour, including the ceremonial role of the viceroy who is, and is seen to be, above politics, and so would the fountain of justice with Her Majesty’s and not some politician’s judges, so would The Queen-in Parliament and the Crown as the auditing executive, so would the Crown as the employer of the public service, rather than the governing party, and so would the Crown as the Commander in Chief - in sum, the whole vast institution which is above politics and which has been with us from the beginning would vanish. This institution, which has been with us since the settlement in 1788, under which we received self-government under the Westminster system, under which we federated and under which we became independent, would disappear forever. And there would be no vacuum. All of this, in every aspect, would fall to the political class.

Perceptive observers who understand this have attempted to construct some sort of faux Crown not so much to fill the void but to protect it from the political class. This has revolved around some collective entity. However, the two principal models proposed in Australia and Canada could not function as the Crown. Neither the vice-regal appointments council of the eminent, consisting of gender-balanced selected former viceroys and chief justices, as has been suggested in Australia, nor a college consisting of the 150 Companions of the Order of Canada, as suggested for that Realm, could possibly replace the Crown. Either would perform the functions of appointing or electing the president and removing him - and there is no guarantee they would do either well. But they would not replace the Crown. The proponents do not, for example, propose that the army should owe allegiance to the council or to the college or that Her Majesty’s judges should become their rotating eminences’ judges or the judges of the college of companions.

These proposals recall that of the Abbé Sieyès, who wished to create a “grand elector” in the French 1799 constitution for the Consulate. This was designed to replace the monarch he had helped first make constitutional and later shamefully despatched to the guillotine. As Walter Bagehot observed, it was “absurd… to propose that a new institution, inheriting no reverence, and made holy by no religion, could be created to fill the sort of post occupied by a constitutional king in nations of monarchical history.” So, in an Australian republic, the new republican office of the president, whether or not appointed by a council of the eminent and whether or not elected, could never replace the Crown as an equally vast institution above politics. Indeed, this is not even suggested. Instead, the proponents choose to ignore the issue.

The question, therefore, has to be asked of all these proposals to graft a minimalist republic onto our constitutional system: where would all of the powers and protections of the Crown - apart from the appointment and dismissal of the viceroys, fall? Into whose lap? The answer is, of course, the politicians’ lap, the same politicians who are already concentrated in the closely linked and controlled executive and legislative arms of government. In the American republic, the politician in the executive and the politicians in the legislature are at least quarantined and isolated one from the other, the founders believing, rightly, that the resulting adversarial relationship, however rigid, would act as a check and balance against the abuse of authority. They were aware of the truth of Lord Acton’s dictum before he enunciated it: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

As Canadian Professor David E. Smith notes, in a minimalist republic, a powerful executive would become that much more powerful. And that was written before he had the opportunity to examine the specific terms of the model presented to the Australian people in 1999. This was famously criticised as offering the only known republic where it would be easier for the prime minister to dismiss the president than his cook.

The alternative model, that of filling these offices by election, would merely turn the incumbents into politicians.

The consequence of the vice-regal offices being cast adrift would not be that they would be endowed with an alter ego, becoming separate Crowns themselves. They would not have -and could not have - two bodies. We, the judges, the armed forces and the public servants, would and could owe them no allegiance. They would become Republican sinecures to be filled either by servants of the politicians or by even more politicians. In their ceremonial and other roles, the public would know they were either politicians or servants of politicians and treat them accordingly.

The Essential Aspects of The Australian Crown

The Australian Crown, the King or the Queen’s political body, is, as it were, a Leviathan at the very centre of the Australian constitutional system. Yet not only do Republicans almost fail to see it, but the Australian Crown is also treated superficially in the academy. This seems to be true even in those subjects offered in the nation’s schools and universities that are relevant, such as civics, history, political science, and constitutional law.

Even when the Crown is recognized, it is more often than not as an anachronistic historical curiosity, a jumble of separate and unrelated offices, each of which it is assumed could easily be converted into a republican sinecure having no relationship one with the other.

This approach is more erroneous than, and just as dangerous, seeing an iceberg as only its visible tip. This approach is analogous to dividing the tip of that iceberg into seven pieces and then saying each is unrelated not only to the others but also to the vast part of the iceberg under the waves, which is being ignored. Whether we like it or not, the Crown remains the nation’s oldest institution, above politics, central to its constitutional system, and with the High Court, the only institution which straddles the component parts of the Commonwealth, State and Federal, and looking outwards through the personal union of the sixteen Crowns and across the Commonwealth of Nations. It was under the Crown that the nation was founded, responsible government was granted, the nation federated, and Australia attained its full and complete independence.

(See: Leslie Zines, in the Commentary to H.V.Evatt, The Royal Prerogative, 1987, Law Book Company, Sydney, pp C1-C2. )

So before we talk about its removal, we have to understand what it is.

Why is the Leviathan not so much understood but not even seen? Is it just ignorance, or is it something more sinister? Rather than attempting an answer to the latter question, let us look at certain important aspects of the Crown.

These are discussed in the following topics:

Succession to The Throne

The rules concerning who should succeed to the throne are contained in the common law, that is, customary law, and as regards religious restrictions, the Act of Settlement of 1701.

Two aspects of the law relating to succession are much criticised today. The first is that a male succeeds before any of his sisters, including an older sister. The other is that a Catholic and a person married to a Catholic cannot succeed. This is part of Australian law, as it is of the laws of all sixteen Realms, including Canada, New Zealand and the UK. The Realms must all agree on any change to the law. It would be open to any Australian government to propose a change. None have, probably because they think any such proposal should come from the British government.

The Palace has indicated that The Queen is not opposed to change.

The Act of Settlement

The Act of Settlement amended the English Bill of Rights following the death of the last child of the then Princess Anne. It provides that (in default of any further heirs of William III of England or Princess Anne) only Protestant descendants of Sophia, dowager Electress and dowager Duchess of Hanover, who have not married a Roman Catholic, can succeed to the English Crown.

The Act provides that Parliament and not the Sovereign acting alone may determine who should succeed to the throne. The Parliament of Scotland was not happy with the Act of Settlement and passed legislation, the Act of Security, 1704, which would have allowed the Scottish Parliament to choose their own successor to Queen Anne.

This could have led to the separation of Scotland. The Crowns of the two countries had been united by the accession in 1603 of King James VI of Scotland to the throne of England as King James I. The possibility of separation was avoided by a Treaty of Union, which was given effect by the legislation of the English and Scottish Parliaments, the Act of Union of 1707.

Article II of the Treaty of Union defined the succession to the British Crown. The Act of Settlement of 1701 became, in effect, part of Scots Law. Sophia died before Anne, so the result of the Act was the succession of Sophia's son, George, in preference to many of his cousins.

Proposals for Change

The rule that the Sovereign can’t be a Catholic has long been on the reform agenda. It pops up from time to time. Sometimes, it arises because some Republican grandee wishes to grab the headlines. Sometimes, it is because a government needs a distraction. There are even times when the proponent is actually genuine. Referring to indications the British government will change the Act if it is returned after the election, Philip Johnston asks in the London Daily Telegraph of 25 September 2005, “Is it time to scrap the Act of Settlement?”The answer is no – amend it. The Palace has indicated The Queen has no objection to a change in this rule, and also the rule that a male of the same rank has precedence over females, male primogeniture. Actually, our common law was for centuries in advance of some other legal systems, such as German Salic law, which could never contemplate a female monarch such as Queen Elizabeth I. That is why Queen Victoria did not succeed to the throne of Hanover.

The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), which involved most of the European powers, began because it was argued that Empress Maria Theresa of Austria should not succeed because of Salic law.

The Act of Settlement and The Glorious Revolution

The change would mean that if Prince William had an older sister, she would succeed before him.

It would seem a change concerning female succession would have little immediate practical relevance. But it would if, say, Prince William or Prince Harry were to marry a Catholic. This does not mean that, as the papers are saying, the relevant legislation, the Act of Settlement, 1701, should be “axed” or “scrapped.” The Act of Settlement is as much Australian, New Zealand or Canadian law as it is British. It is a significant part of the constitutional reforms, often referred to as the "Glorious Revolution” or “ Bloodless Revolution”, which began in 1688. The joint Sovereigns, King William III and Queen Mary II agreed to those reforms. Mary’s father, King James II, was deemed to have abdicated when he fled England, destroying important state documents and throwing the Great Seal into the Thames. Parliament was unhappy with James, who seemed to see himself more as an absolute monarch on the model which now prevailed on much of the continent. Parliament would not agree to the Crown descending to James’ young son, Prince James Francis Edward Stuart. This was because both father and son had gone to France and were under the protection of the Realm’s mortal enemy, King Louis XIV of France, who had clear ambitions to control all of Europe. Instead, James’s daughter and her husband, the Dutch Prince William of Orange, were invited to take the throne.

William, a Calvinist, was incidentally in alliance with the Pope in the League of Augsburg, a defence against French aggression.

The Act of Settlement is Important

It introduced the important rule that judges were no longer appointed “at pleasure,” but “during good behaviour” and could only be removed by a resolution of both Houses of Parliament.

This was the beginning of the separation of powers, which Montesquieu later discovered in the English constitution.

This separates the judicial power from the executive and legislative powers, a doctrine which was taken to the United States, Australia and other lands.

This is yet another example of allowing a constitution to evolve through trial and error rather than letting some obsessed individuals or some movement declare what the constitution should be.

Quite often, they don't understand what they are doing. Or there are unintended consequences in following them. Or worse, they have an agenda which they are keeping secret.

Australia's so-called Republicans encompass each of these three evils.

Amending the Act of Settlement

Under the present constitutional arrangements governing the personal union of the sixteen Crowns of the Commonwealth, the Realms agree that any change to the succession will be done only by common consent.

This principle may be found expressed in the Preamble to the Statute of Westminster, 1931, which was adopted in Australia in 1942.

The better process would be for the British government rather than a private member to draft an amending Bill in consultation with the Palace, consult with the governments of the Realms and then for it to be introduced into the UK Parliament, where any objections could be considered.

Objections are more likely in the UK because of religious issues which do not apply in other realms.

Before Royal Assent is granted, it could then be introduced into the Parliaments of the other Realms.

In 2005, in O'Donohue v. Canada, a Canadian lawyer opposed to Canada’s oldest institution, her Crown, sought a declaration that the Act of Settlement breached the Canadian Bill of Rights, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The ruling of the Superior Court of Justice of Ontario would be a persuasive precedent if some action were brought in Australia, New Zealand and other Realms.

Similar litigation in the UK was also unsuccessful.

The Canadian Court said that to make such a declaration would make the constitutional principle of the union under the Crown together with other Commonwealth countries unworkable.

It “would defeat a manifest intention expressed in the preamble of our Constitution, and would have the courts overstep their role in our democratic structure.”

Those who whinge most about the Act of Settlement – politicians who have an agenda to change the Constitution - have never done anything about amending it.

It is open to any government, including the Australian government, to propose changes.

Accordingly, we can assume they are not genuine and are only using the Act of Settlement as a whipping boy.

Australia's Federation

Discover the story behind federation in Australia with this introductory video.

The PEO, part of the Department of the Senate, welcomes respectful and relevant comments to PEO videos.

Comments which do not follow the general rules of respectful civil discourse will be removed. This includes comments that include language that is degrading, discriminatory, threatening, harassing or defamatory, incites violence or contains profanity.

Advertising and comments which infringe copyright will not be accepted.

Repeat offenders may be blocked from contributing.

According to the Macquarie Dictionary, a republic is a state where "the supreme power resides in the body of citizens entitled to vote and is exercised by representatives chosen directly or indirectly by them."

(For more detail from the dictionaries, go to Definitions.)

Usage and political theory

Sir Thomas Smith introduced the term "republic" to describe the English system as long ago as the sixteenth century. He was an English diplomat and one of the most outstanding classical scholars of his time.

He studied at Padua and was made Regius Professor of Civil Law and Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University. He was also a Member of Parliament, an ambassador to France and as a secretary of state, a very close and trusted confidante of Queen Elizabeth I.

His book, "De Republica Anglorum; the Manner of Government or Policie of the Realme of England," was published in 1583. He intended to show how the English system differed from and was superior to others.

"No one", said the renowned historian, FW Maitland, "would think of writing about the England of Elizabeth's day without paying heed to what was written about that matter by her learned and accomplished Secretary of State." The French political philosopher Montesquieu, one of the most significant figures of the Enlightenment, declared England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to be a 'republic hiding under the form of a monarchy'.

Eighteenth-century republican theorists did not see constitutional monarchy as incompatible with genuine republicanism, says Professor Brian Galligan, A Federal Republic, 1995, p.4. Montesquieu praised the English constitution as an ideal model for republican government

Usage in Australia

The statement that Australia is already a republic may surprise many. But this would have been the assessment of the great political philosophers Rousseau and Montesquieu. As Sir Henry Parkes, to many the Father of Federation, wrote:

"EverConstitutionon is, in reality, a republic. There is just as much a republic in England as there is in the United States, the only difference being that in the one case, the word is not used, and in the other, it is."

Cardinal Moran, the leader of Australia's Catholics during the final phase of the nineteenth-century movement for Federation, described our constitutional system as the "most perfect form of republican government".

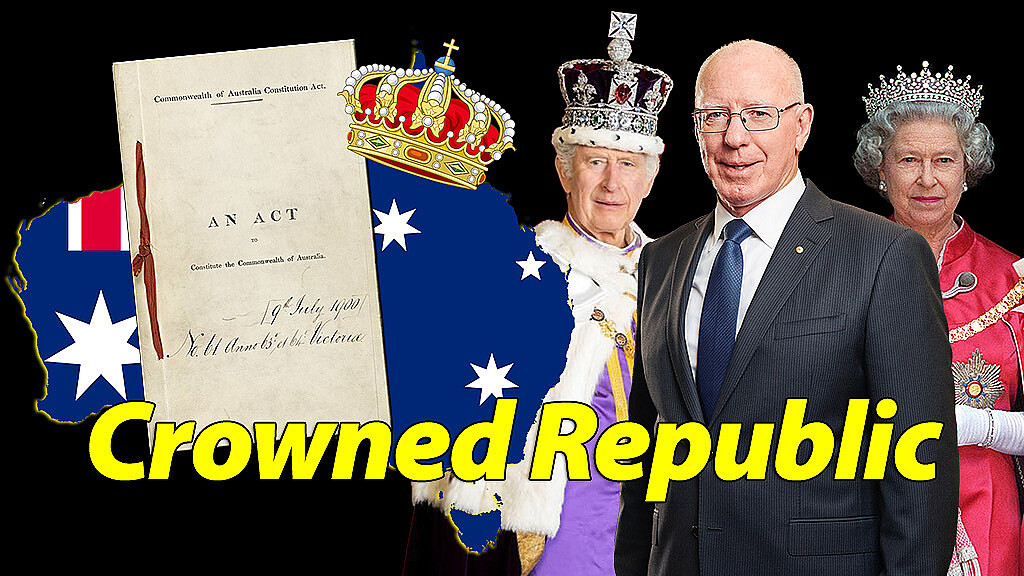

The word choice to describe our Federation, the Commonwealth of Australia, is consistent with this line of reasoning. After all, the word "Commonwealth" is the English equivalent of a republic. But as with the word "republic", it does not necessarily mean a state without a monarch or sovereign. The Republic Advisory Committee, established by Prime Minister Paul Keating in 1993, chaired by Malcolm Turnbull and consisting only of Republicans, conceded that it might be appropriate to regard Australia as a crowned republic. (The Australian Republic, Vol 1, 1993, page 3)

The word "republic" by itself is so imprecise as to be almost meaningless. It requires some qualification to explain what is intended. This site distinguishes between crowned republics (constitutional monarchies) and politicians' republics.

Politicans' republics can be classified in various ways. This does not purport to be an exhaustive classification. Falling outside these are, for example, absolute monarchies, which have existed historically in France under Louis XIV and exist today in Saudi Arabia. But in most countries today, the more significant part would be either crowned republics or politicians' republics. In Australia, the Republican movement proposed a republic where the politicians chose and closely controlled the president. This was rejected in 1999. Although they will not today reveal what sort of political republic they want, the two most talked about is some variation of that left in 1999. The other is one where the president, and presumably the vice president, the six governors, the six lieutenant governors and the territory administrator are all politicians.

As we are arguably already a republic, albeit crowned or disguised, and as our constitutional system is one of the most successful in the world, readers could be excused for wondering what all the fuss is about. And why have millions and millions of dollars already been spent and more proposed on what is an elite folly? More importantly, we may wonder why anyone would wish to change any of the fundamental features of such a successful constitutional system, of which there are so few in the world.

The term "crowned republic" has been used by leading supporters of the Australian Crown in our constitutional system, including the former Prime Minister, John Howard, the former Minister, Tony Abbott, the former High Court judge, Justice Michael Kirby, and the former NSW Court of Appeal judge, Justice Ken Handley.

".... in many respects, Australia, like the United Kingdom, is already a republic," declares Alan Fenna, Professor of Politics at the John Curtin Institute of Public Policy, Curtin University, in a volume published in honour of the late Professor George Winterton, one of Australia's leading constitutional lawyers. ( The Incremental Republic in Constitutional Perspectives on the Australian Republic, ed. Sarah Murray, Federation Press, Sydney, 2010, pp. 127,128)

Professor Fenna is a leading proponent of constitutional change to remove the Crown.

"Well over a century ago, Walter Bagehot, whose 'canonical works' have done more than even Dicey's to define 'the English Constitution', was characterising Britain as having a 'veiled republicanism' system.

"Bagehot was undoubtedly exaggerating – though not significantly – for effect, he was identifying the unmistakable trend, and since then, the veil has become diaphanous.

"The metaphor was less apt to Australia, where what Bagehot called the 'dignified 'part of the Constitution scarcely plays that sort of masquerading role relative to what he calls the 'efficient' part, but the underlying message is equally applicable.

"Following on from Bagehot, (Professor) Brian Galligan described Australia as being a 'disguised republic', but James Bryce's earlier term 'Crowned Republic is the more apt."

Like many of the world's leading countries, Australia is already a Crowned Republic.

100 Years The Australian Story Episode One -Child of the Empire - 1901 Federation

Australian Federation Day (1901) (in colour)

The current debate

The current constitutional debate in Australia is usually presented simplistically.

For example, in some opinion polls, people are asked whether Australia should become a republic. As we point out in the Definitions section, the word "republic" is so vague as to be almost meaningless. Australia is already a republic, and more than, as Mrs Helen Clark, NZ Prime Minister, said in the Evening Post on 4th March 2002, a "de facto republic."

The essential question is, what sort of republic is being proposed? The Australian people decided the nation should be formed as a constitutional republic. We were federated as an indissoluble Federal Commonwealth under the Crown and the Constitution. The Crown was not new in 1901. It is, in fact, our oldest legal and constitutional institution.

It came in 1788 and since then has evolved into the Australian Crown. (The ORIGIN of the Australian Crown is discussed separately.) At the centre of a crowned republic is an institution above politics. It acts as a check and balance against the political branches, the houses of parliament and the ministers who effectively constitute the government.

This may be distinguished from a republic, where the politicians either appoint and control the head of state to varying degrees or where the head of state is an elected politician.

On this site, these are categorised as "politicians' republics."

The current constitutional debate is whether the fundamental nature of our "indissoluble Federal Commonwealth under the Crown "should be changed by removing the Australian Crown. The model preferred by most Republican delegates at the 1998 Constitutional Convention, the Referendum Model, was put to the people in the 1999 referendum.

It was rejected nationally, in all states and 72% of electorates. The Rudd government has indicated that it will raise the issue again, but not in its first term. Before any referendum, the Rudd government said there would be a plebiscite. ( No details of the proposed change are revealed in a referendum). This was the principal issue at the 2020 Summit.

Before deciding, Australians should compare crowned republics with politicians' republics.

(The well-being of the people in different countries –their health, education and wealth - is regularly measured by the United Nations Human Development Index, HDI. This allows us to compare crowned republics with politicians' republics.)

Those who support keeping the current system do not rely on the attractiveness of crowned republics, the Magic of Monarchy or the widely acknowledged personal qualities of The King and the Queen, our Sovereign.

At the time of the 1999 referendum, the Republicans were also campaigning against the Australian Flag without agreeing on what the new Flag would be. Some Republicans now say this is a separate issue; others say the Flag must change if the people approve a change to a politicians' republic in any future referendum.

In the 1960s, a group of intellectuals in Australia held the belief that the Australian Crown's problem stemmed from the obligation felt by their social class to display deference towards Britain. However, this matter went unnoticed by the British. It is crucial to acknowledge that our constitutional system is entirely distinct from the personal psychological issues of a small number of Australian intellectuals.

The rise of Republicanism was not primarily motivated by a sense of inadequacy towards Britain but rather stemmed from a cutthroat political battle that took place in 1975. Two politicians engaged in this struggle, both of whom were unwilling to compromise and make concessions. This intense power struggle ultimately gave rise to the prominence of Republicanism.

The Leader of the Opposition, Malcolm Fraser, was impatient for government and not willing to wait the normal 18 or so months for an election to be held. Meanwhile, the unpopular Prime Minister, Edward Gough Whitlam AC QC, was not prepared to have his term shortened. Fraser used his numbers on the Senate to delay the supply until the Prime Minister advised an early election. It has been unconstitutional since the reign of King Charles I for a government to rule or spend money without supply being granted by Parliament. The Whitlam government tried to find ways of continuing without supply, such as bank loans, but they were refused. Eventually, the Governor-General would have had to act. On November 11, 1975, instead of a general election, Mr Whitlam advised a half-senate election. The timing of this would depend on the state governors, who were mainly hostile. Even if the election were favourable to Mr Whitlam, new senators would not take their place until July 1, 1976.

In the year 1975, Australia experienced a highly controversial political crisis that left a lasting impact on the nation's political landscape. During this time, the Governor-General made the unprecedented decision to dismiss Mr. Whitlam's commission and instead appointed Mr Fraser to form a new government. Despite initial hesitation, Mr Fraser eventually agreed to act as a caretaker of the government and proposed a double dissolution of Parliament. This led to a general election on December 13th of the same year, which resulted in a significant victory for Mr Whitlam's opponents. While the crisis was resolved democratically, it sparked widespread discussions and calls for constitutional changes to limit the powers of the Governor-General and the Australian Crown, highlighting the need for reforms to ensure a fair and just political system.

There was growing interest in making a change, but it wasn't until Paul Keating became Prime Minister that the Australian government made it a priority. Unfortunately, Keating was defeated in the 1996 election, but his opponent, John Howard, decided to address the issue by proposing a constitutional convention before the election. The convention took place in 1998, and a referendum followed in 1999. Despite widespread political, media, and financial support, the referendum was ultimately defeated across the nation, in all states, and in 72% of electorates.

A Republic of the Arts

The arts have had a long association with nationalistic Australian republicanism. It goes back to Henry and Louisa Lawson, who embraced the narrow, racist and isolationist vision of a new Australia espoused by the Bulletin. Mark McKenna also includes the painter Adelaide Ironside and the poet Charles Harpur as "artistic" Republicans.

In more recent years, we have had Donald Horne, Patrick White, Geoffrey Dutton, Les Murray and Arthur Boyd. McKenna attributes the republicanism of these artists and writers to the strong sense of nationalism they asserted through their work in this seemingly isolated country.

Republicanism became a convenient refuge for artists who wished to signify their separation from the "cultural Mecca" of London. They feared a form of psychological dependence that would shackle their creative endeavour in making Australian art. Concerns about a "cultural cringe" are not new.

P.R. Stephensen insisted as long ago as 1936 on the impossibility of a distinctly Australian culture developing while Australia remained intellectually or politically dependent on the British Empire. In the 1960s, this sentiment developed significantly, led largely by writers such as Geoffrey Dutton and Donald Horne, who spent time in England in the 1960s.

But by then, the campaign seemed curiously dated. Weren't these artists fighting yesterday's battles? Hadn't they noticed that the dominant cultural influence in Australia was now that of the United States? As Michael McKenna observes, republicanism was being led by intellectuals who had only belatedly decided that they no longer needed to feel inferior to Britain.

Meanwhile, most Australians who identified with Americana were seeing the revival of Australian film, watching for the first time Australian television dramas, and hearing at least some Australian music.

The cultural cringe

No doubt the average Australian wondered, if they paid any attention at all to the issue, why these intellectuals were worrying about British influence.

So we have the phenomenon of members of the Australian intelligentsia leading from behind as French politician Alexandre Augustine Ledru Rollin exclaimed, "Ah well! I am their leader, I really had to follow them."

Given the profound impact that writer Donald Horne was to have on the later Republicans, it is worthwhile to consider his early approach more. From a contemporary perspective, they seem to be only of academic interest. His observations about British domination of Australian culture are obviously no longer accurate reflections of Australian society - the Australian sun has long set on British cultural predominance.

But Horne's conclusions are historical in that he spends a great deal of time discussing the “ problem” of past perceptions of Australia rather than those which prevail today.

In 2008, the Lowy Institute Poll showed that from a list of countries of interest to Australia ( New Zealand was not included), Australians are by far most favourably disposed towards Great Britain. Horne wrote that for the extreme empire loyalists of the past, loyalty was primarily a matter of the empire and the monarch. Loyalty was due to Australia precisely because Australia was British.

To the extent that Australians deviated from "Britishishness”, they denied their heritage and their destiny. Even to distinguish between the interests of Australia and Britain was disloyal. It is telling that even in 1965, Horne preferred to address a mentality that existed in Australia in the past tense.

Overlooking the example of Canada, Horne claimed the crisis was that Australia has no identity and its only hope is to pursue republicanism. So, some politicians’ republics are necessary because Australia lacks an identity.

The dismissal

The dismissal of the Whitlam government in 1975, followed by an election, changed the Republican debate. What was a curious academic school, the obsession with a cultural cringe suddenly had legs. It is worth recalling the immediate causes of the 1975 crisis.

They were Leader of the Opposition Malcolm Fraser's impatience for government and the determination of the Whitlam government that it would try to govern without supply, that is, without the authorisation of funding by parliament. It was the Governor-General's decision to act before the supply ran out that brought the crisis to an end.

The crisis was in no way caused, provoked or exacerbated by The Queen. But logic is not necessarily a guide for political action, and many blamed the monarchy rather than the politicians who had actually caused the crisis. So the dismissal provided a new source of Republican sentiment.

Until then, the Labor Party had been as monarchist as the Liberal and Country Parties. Labour leaders such as John Curtin, Dr H.V. Evatt and Ben Chifley were as a royalist in sentiment and in action as R.G. Menzies. After all, it was our great wartime prime minister, John Curtin, who recommended that a Royal Duke be made Governor-General.

A New Labor Platform

But in July 1981, six years after Whitlam's dismissal, a national conference of the Labor Party voted to support a republic. There were in fact two motions, this one from the floor, and another from the executive, asking for an inquiry on the subject and a report. According to the historian Alan Atkinson, the motion from the executive should have been put first, but Neville Wran, the national president, gave priority to the motion from the floor. It was carried unanimously. Labor was committed to a republic without any form of consultation or discussion within the broader party.

A motion in 1991 for a public education campaign, culminating in a referendum to make Australia an "independent" republic on 1 January 2001, was carried - but "not very vigorously", according to the then ALP president.

What then are we to make of something being official ALP policy? The first platform of the ALP aimed for the total exclusion of "coloured and other undesirable races". For many years Labor was committed to the widespread nationalisation of industry and the banks. Both of these policies have not only been abandoned but reversed. Will republicanism stay as ALP's official policy?

Before he endured the indignity of dismissal, Gough Whitlam was asked whether it was correct that he wished to transform the office of Governor-General into a presidency.

He replied: “No, I do not think that is said. I have used the term that the GovernorGeneral is viceroy, and some people seem to think that is an extraordinary concept, but constitutionally, it is quite obvious. He is the stand-in for the Queen when she is not in residence here. He can do everything that she can do as head of state. The system ... works quite well.

“After all, no government of any political complexion can be better pleased than with a system where the head of state, the ceremonial head, holds the position for a certain number of years on the nomination of the national head of government. The system works very well and our governors-general, certainly the Australian ones, have always been top men.”

So before his dismissal, Mr Whitlam clearly thought the Australian system quite agreeable. He is, of course, entitled to change his views. In 1983 he wrote that he believed not merely in a symbolic change but in large-scale substantive alterations to the Constitution.

The case for a republic, he says, is not primarily directed against the monarchy "but against the faults" in the Australian constitution.

He believes that the case rests not so much on the need to sever links with the Crown but on the need to strengthen Australia's own institutions and democratic safeguards.