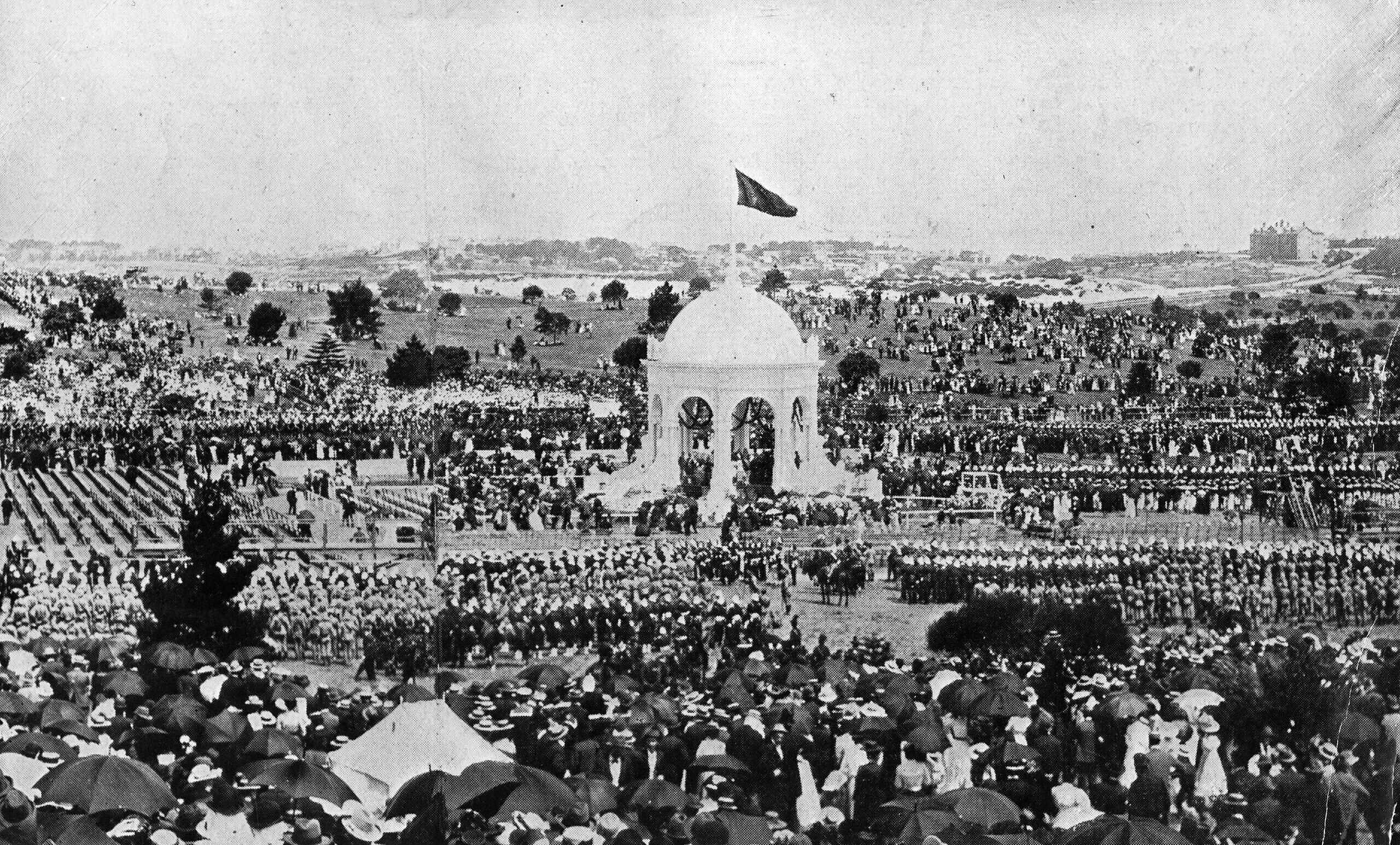

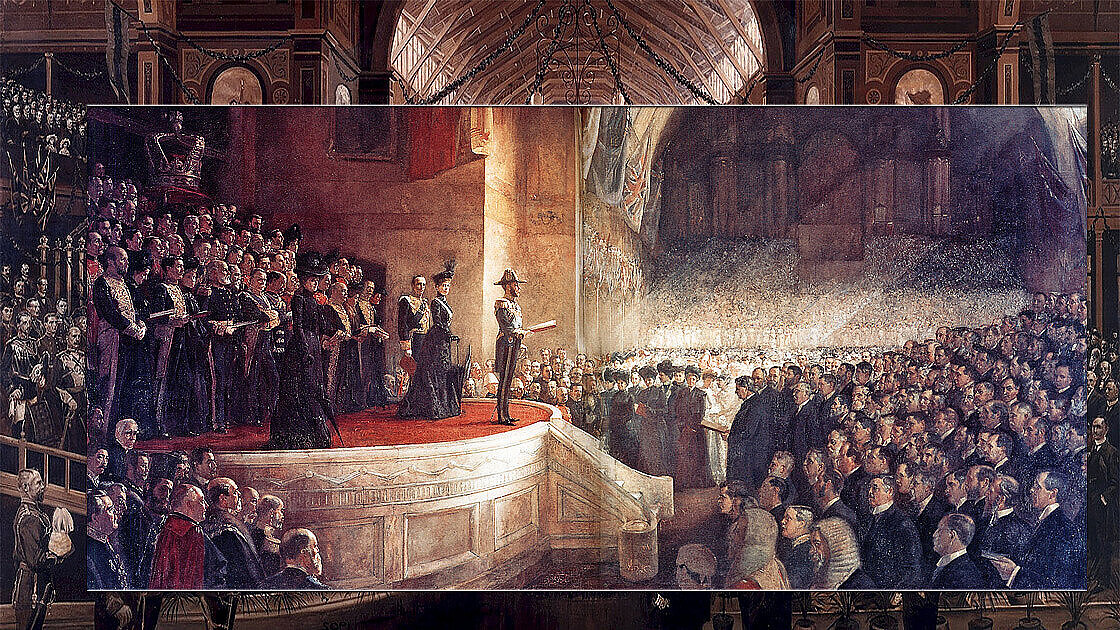

[Charles Nuttall: The opening of the first Federal Parliament, 9 May 1901, Museum Victoria Collection]

Centralism

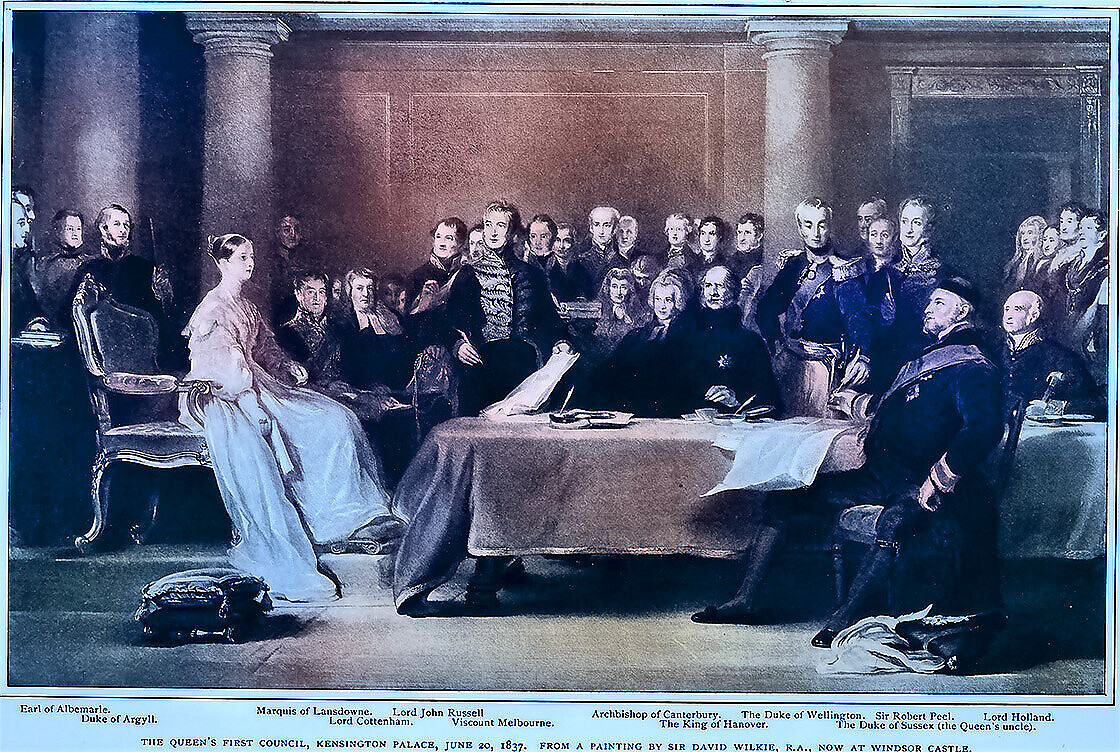

Federation, although first proposed by the British, was our own decision. This was to establish “an indissoluble Federal Commonwealth under the Crown ... and under the Constitution".

The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act provided that the six self-governing Australian colonies would be “Original States” in the new Commonwealth of Australia.

The law-making power of the new Commonwealth was to be vested in a Federal Parliament, which was to have only those powers clearly set out in the Constitution. Some powers would be exclusive to the Commonwealth, such as making laws for Commonwealth Territories, raising military forces to defend the Commonwealth or minting coins.

Other powers would be shared with the states (the “concurrent powers”), for example, banking, insurance, corporations, marriage and divorce. But for each of these, the Commonwealth law would prevail if there were an inconsistency with State laws.

The powers not listed, the so-called “residuary powers, were to be exclusively the States’. This would include land, school and university education, police, prisons, state taxes, including state income taxation, mining, roads, railways, and fisheries.

Our federation can only be seen as a culmination of our colonial history and in the context of a strong desire and intention to retain the self-governing states as important entities in themselves.

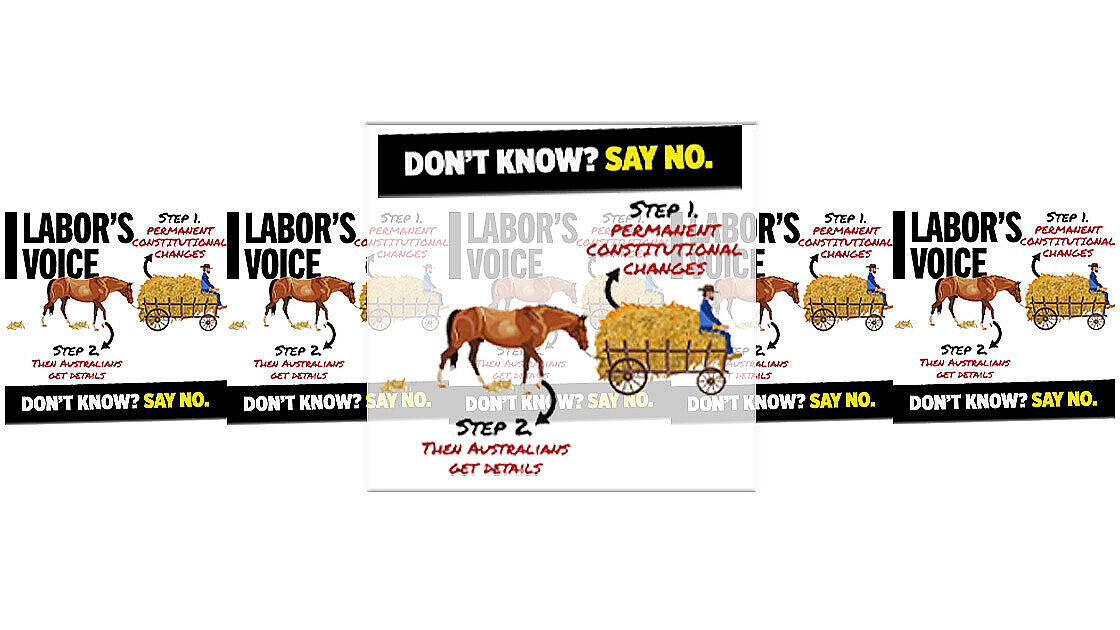

Although the Constitution can be changed, most proposals to expand federal powers have been rejected by the people. However, the powers of the Federal Parliament and Federal government have been expanded significantly since 1901.

It is relevant to ask two questions. First, how has this happened, and second, is it in the national interest?

"The States" shall mean such of the colonies of New South Wales, New Zealand, Queensland, Tasmania, Victoria, Western Australia, and South Australia, including the northern territory of South Australia, as for the time being are parts of the Commonwealth and such colonies or territories as may be admitted into or established by the Commonwealth as States. Each of such parts of the Commonwealth shall be called "a State": section 6."

Original States" shall mean such States as are parts of the Commonwealth at its establishment.

This desire to retain the states' autonomy and freedom from federal control explains the long delay until 1986 in ending their residual links with the British Crown. Until 1986, appointments of State Governors were made by The Queen on the formal advice of British ministers. This had only continued because the States were suspicious of Federal governments. The solution was unique in the Commonwealth of Nations and involved each State Premier advising The Queen of Australia on matters relevant to his or her State. That solution was only found with the involvement and approval of The Queen: Anne Twomey, The Chameleon Crown: The Queen and Her Australian Governors (Sydney: Federation Press, 2006).

The Expansion of Federal Power

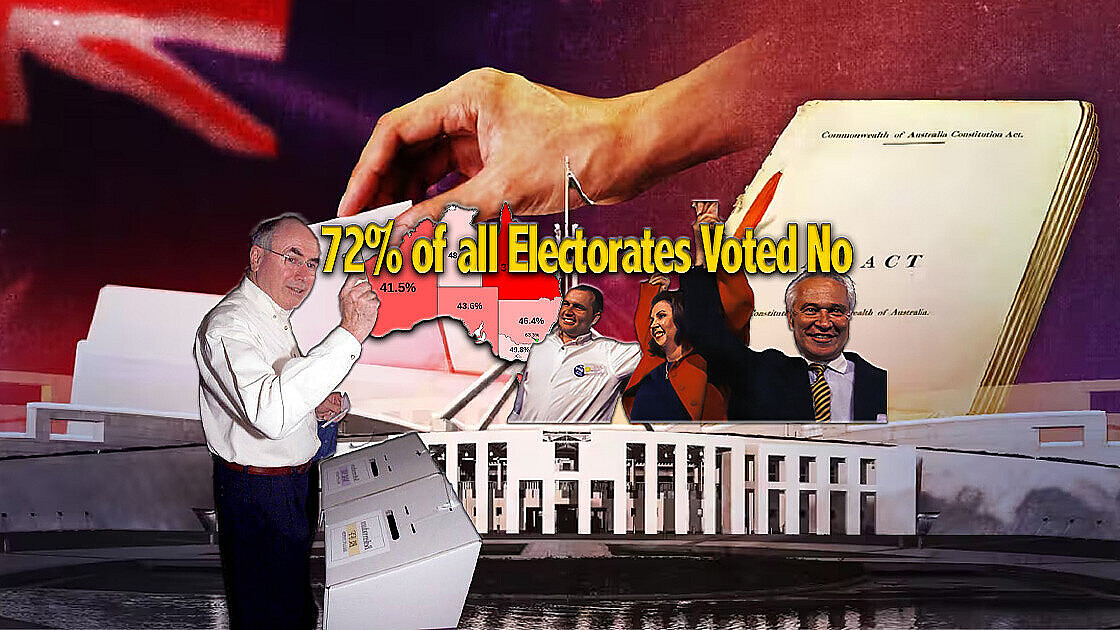

The expansion of federal power has been achieved mainly against the wishes of the people who have generally refused extensions of Federal power. The expansion has been done principally through the interpretation of the Constitution but by the Commonwealth controlling revenues, including income taxation. This has led to the Commonwealth funding the States to a level unknown in most other federations, as the graph below illustrates. This is sometimes referred to as “Vertical Fiscal Imbalance”.

Those who designed the first federation, the United States, stressed the importance of state governments obtaining their revenue from their electors.

This imbalance suits some state politicians in that they do not have to answer to their electors for the spending of taxes collected from them. The result is that the people are confused as to which government is responsible for which matters. State governments lose the incentive to perform well in their areas of responsibility.

Under our constitutional system, only two institutions straddle the Commonwealth-State divide. One is the Crown; the other is the High Court. Both are intended to be above politics. Neither should have a political agenda. While the Crown remains unquestionably above politics, the High Court, or a majority of the court, has occasionally wandered beyond its role, never more so than in some of their more controversial decisions during the 1990s.

One policy which has dominated the court since 1920, and for which there is no constitutional authority, is centralism, once disguised as an objective exercise in literalist interpretation. This began as long ago as 1920 in the decision of the High Court in the Engineers' Case [ii].

According to Professor Geoffrey de Quincy Walker, the case inaugurated a method of one-sided interpretation that contradicted the constitution's plain intention, ignoring the first principles of legal interpretation and violating the people's wishes as consistently expressed in constitutional referenda, as well as mocking their sovereign power. This, he says, denied the people the advantages of competitive federalism and increased the burden, cost and remoteness of government, more recently pushing the constitutional order to the brink of breakdown [iii].

The court has continued this trend in the recent decision in 2006 in the WorkChoices case [iv]. Whether or not we agree with the changes in the Howard Government's industrial legislation, it is difficult not to be concerned as to the consequences of this decision on the future of the federation. The court indicated, with Justice Michael Kirby and Justice Ian Callinan dissenting, that the Commonwealth's use of the corporation's power is almost without limits. The court had two decades ago come to a similar conclusion with respect to the external affairs power [v].

It cannot be said that this vast expansion of federal power was the intention of the founders or that it reflects the wishes of the Australian people. In fact, most of the failed referenda which involved giving more power to Canberra--some even rejected more than once--have been circumvented by High Court decisions which have favoured the Commonwealth[vi].

Professor Greg Craven observed that "the states should be in absolutely no doubt" that this latest decision "is a shipwreck of Titanic proportions. Not since the 1920s has the court struck such a devastating blow against Australian federalism ..."

"How," he asked, "a court can weigh every tiny word of a constitution without grasping the central premise that it was meant to create a genuine federation must baffle historians and psychoanalysts alike." This is, he said, "the greatest constitutional disaster" to befall the States in 80 years.

Reflecting the warning of Justice Kirby in his strong dissent, Professor Craven warned that the federal authorities now have an "open cheque to intervene in almost any area of state power that catches its eye, from higher and private education, through every aspect of health, to such matters as town planning and the environment" [vii].

That this should worry conservative constitutionalists is well explained in the dissent of Justice Callinan. That this should also worry conservative politicians and their supporters was demonstrated when P.P. McGuinness warned that this decision could and probably would work both ways. A future government could attempt to regulate prices and incomes, re-regulate the labour market and, if socialism becomes fashionable again, effect the nationalisation of any sector of the economy. He wrote that the majority had "destroyed our federal system of government". They had effectively abolished any logical or sensible limitation of the federal powers [viii].

Professor Craven said there is not the "least chance that Canberra will use these powers comprehensively to take over such policy nightmares as our health and education systems". Instead, based on long practice, Canberra will employ its new capacity to "cherry-pick politically attractive items and to embarrass uncongenial state governments". In other words, the politicians will, thanks to the High Court, be allowed to behave like politicians.

In handing down its decision on November 14, 2006, the High Court majority said the fact the people may have indicated their objection to a specific change is of "no assistance" to them. That is, the fact the people may have refused to grant some power to the Commonwealth is to be completely ignored. The High Court has turned its back on--or, as Professor Walker says, mocked--the "quasi sovereignty" with which the founders specifically endowed the people [ix].

The result is that the High Court has abdicated much of its role as an important check and balance. As Professor Craven says, we no longer have "even a deeply biased constitutional umpire". The High Court "has given Canberra the key to the constitution".

[i] The Western Australian government says Vertical Fiscal Imbalance:

-

Reduces the accountability of governments to their electorates because it is not clear which level of government is responsible when community expectations for services and infrastructure are not met;

-

Facilitates the attachment of conditions by the Commonwealth to a significant proportion of State funding, which, if not consistent with overall community priorities, can result in a misallocation of resources. Conditions are attached to around 40% of Commonwealth grants to the States;

-

reduces incentives for States to put in place growth‑promoting policies and infrastructure, as the costs are borne by the State, while the tax benefits flow primarily to the Commonwealth (which retains the majority of the nation’s taxes) and other States (through the equity principles used to allocate Commonwealth grants among the States); and

-

exposes State governments to budget uncertainty vis‑à‑vis Commonwealth decisions about the level of grants, including the inherent temptation to shift any national budget shortfalls onto the States.

The WA government says the GST-related tax reforms (which involve the Commonwealth government raising a GST and providing the proceeds to the States in the form of grants) have increased the States’ dependence on the Commonwealth, as the States have been required to abolish a number of their own taxes over time as part of the tax reforms (such as financial institutions duty and debits tax.

[ii] Amalgamated Society of Engineers v. Adelaide Steamship Co. Ltd. (1920) 28 CLR 129.

[iii] "The Seven Pillars of Centralism: Federalism and the Engineers' Case", Proceedings of the Fourteenth Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society, 16 June 2002, vol. 14.

[iv] New South Wales v Commonwealth (WorkChoices Case) (2006) 231 ALR 1.

[v] Commonwealth v Tasmania (Tasmanian Dams Case) (1983) 158 CLR 1.

[vi] David Flint, The Cane Toad Republic (1999), p. 160.

[vii] The Australian, 17 November 2006.

[viii] The Australian, 15 November 2006.

[ix] Quick and Garran, op.cit., p.988. Professor Walker prefers the term "sovereign power".

The Case for Federalism

The arguments against federalism dominate the media and politics. The High Court only gives nominal respect to federalism while whittling away the powers of the States.

A frequent argument is that the States should be abolished and replaced by smaller regions. The problem with that is that even if this could be achieved, the regions would be even more dependent on the Federal government.

Professor Walker observes that for "a framework of government that has created a new nation and given it external security, internal peace, stability, progress and prosperity throughout the most violent, turbulent century in human history", our constitution has been subjected to an "inordinate" amount of negative comment.

He says the chief obstacle to a balanced appraisal today is the failure of the critics to consider the advantages of federalism. He lists 10: the right of the citizen of choice and exit, the possibility of the experiment, the accommodation of regional preferences and diversity, participation in government and the countering of elitism, the better protection of liberty, the closer supervision of the government, stability, fail-safe design, competition and efficiency, and the resulting competitive edge for the nation. Professor Walker writes that the debate has hitherto focused exclusively on its disadvantages. More recently, there has been an increasing acceptance of the advantages of federalism. Those advantages were noted in a major Business Council report [ii]. They were stressed in a major report in 2007 by Dr Anne Twomey and Professor Glenn Withers [iii] to the newly formed Council for the Australian Federation, which brings together all of the Australian governments, with the exception of the federal government.

They argue that by focusing too much on the problems in the operation of the federal system, we forget about the benefits of the federation, including checks on power, choice and diversity, customisation of policies, competition (although they do not mention it, unilateral action by the Queensland Government led to the abolition of that inequitable tax, death duties, in all states and at the federal level), creativity and co-operation.

The CFAF report drew attention to widespread media coverage of the BCA report, which suggested that the cost of inefficiencies in the federal system, or perhaps the federal system itself, cost $9 billion for 2004-2005, or $450 per Australian, a conclusion which was highly qualified in the report itself. The authors of the CFAF report preferred to measure the benefits of federations from a comparative OECD study, which found that, for the last half-century, federations had a 15.1 per cent advantage over unitary states. In addition, they measured the benefit of fiscal decentralisation, which ranges between an average of 6.79 per cent to "federal best-practice", exemplified by Canada, Germany and Switzerland, of 9.72 per cent.

Australia, they conclude, is the most fiscally centralised of the OECD federations, demonstrated by the fact that the states and territories raise only 19 per cent of taxes but are responsible for 40 per cent of public spending. As long ago as at the time of the creation of the United States, it had been realised that such vertical fiscal imbalance is inimical to good government. As a principle, governments should be responsible to the people who elect them for the money they spend. The CFAF report argues that the benefit to Australia from being a federation is already 10 per cent and that this could be raised significantly by further decentralising our taxation system. The result would be to raise average incomes by $4,188 per annum.

To read more about these issues, go to “The Future of Our Federation: in safe hands?”

[i] "Ten Advantages of a Federal Constitution", Proceedings of the Tenth Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society, Brisbane, 7-9 August 1998, vol. 10, chapter 11; see also Greg Craven, "Federalism and the states of reality", Policy (Centre for Independent Studies), vol. 21, no. 2 (Winter 2005), pp. 3-9.

[ii] Business Council of Australia, Reshaping Australia's Federation: A New Contract for Federal-State Relations (2006).

[iii] Anne Twomey and Glenn Withers, Federalist Paper I: Australia's Federal Future, a report for the Council for the Australian Federation (April 2007).