Emergence Of Nationhood And Constitutional Conventions

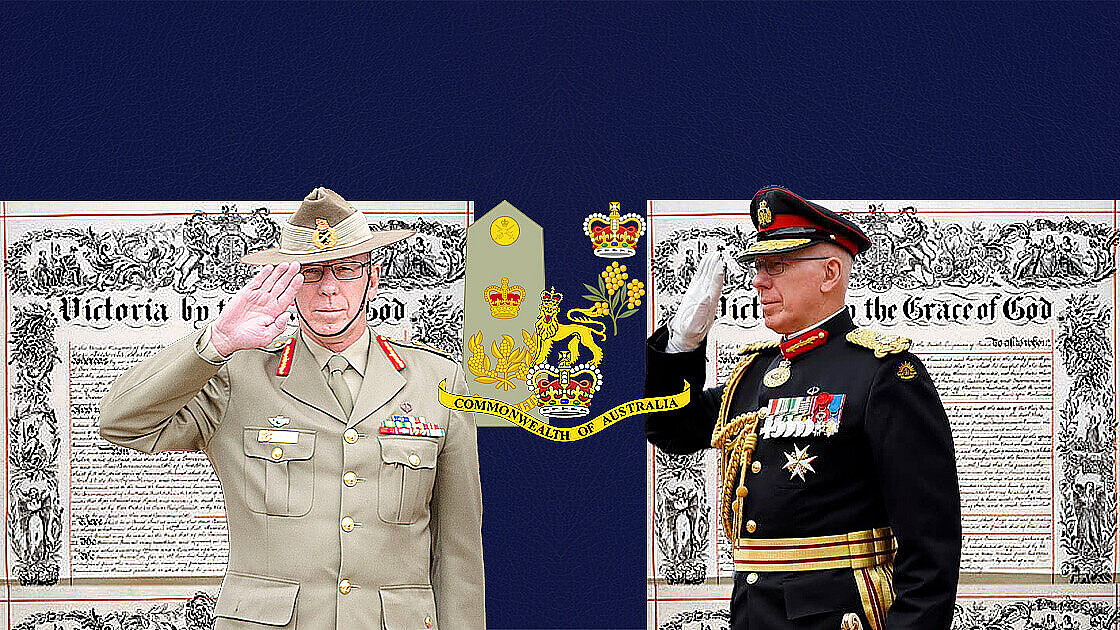

An understanding of the gradual development of the role of the crown, including the governor-general and the queen, requires such developments to be viewed in the context of the development of Australia as an independent nation. The developments involved changes in convention and, less often, statutes. By convention, we mean those usages or customs that are not to be found in the statute books but nevertheless are binding. In jurisdictions governed by a written constitution, there is a greater reluctance to acknowledge the role played by convention than there is where no such document exists, as in the United Kingdom.

THE AUSTRALIAN CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM

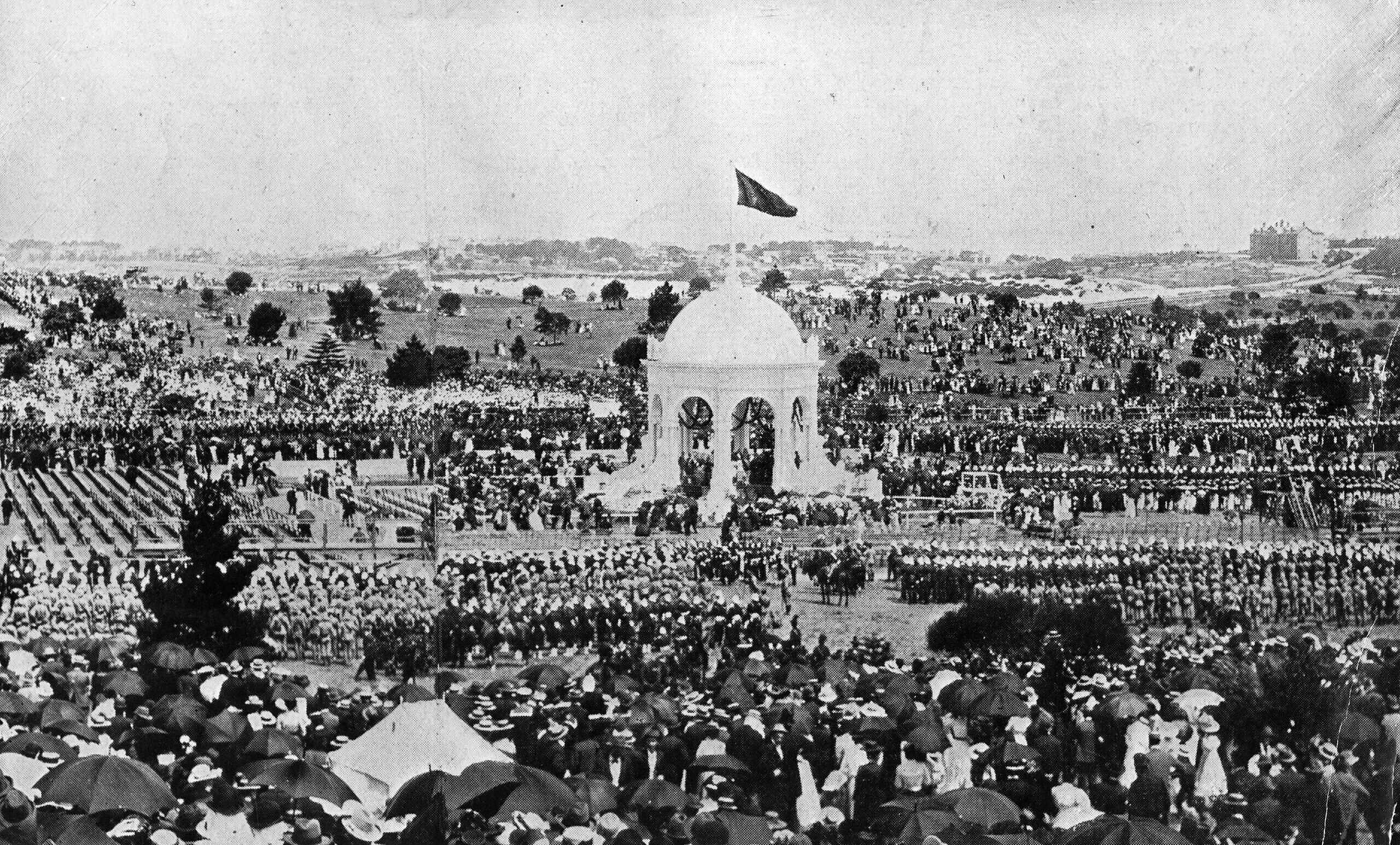

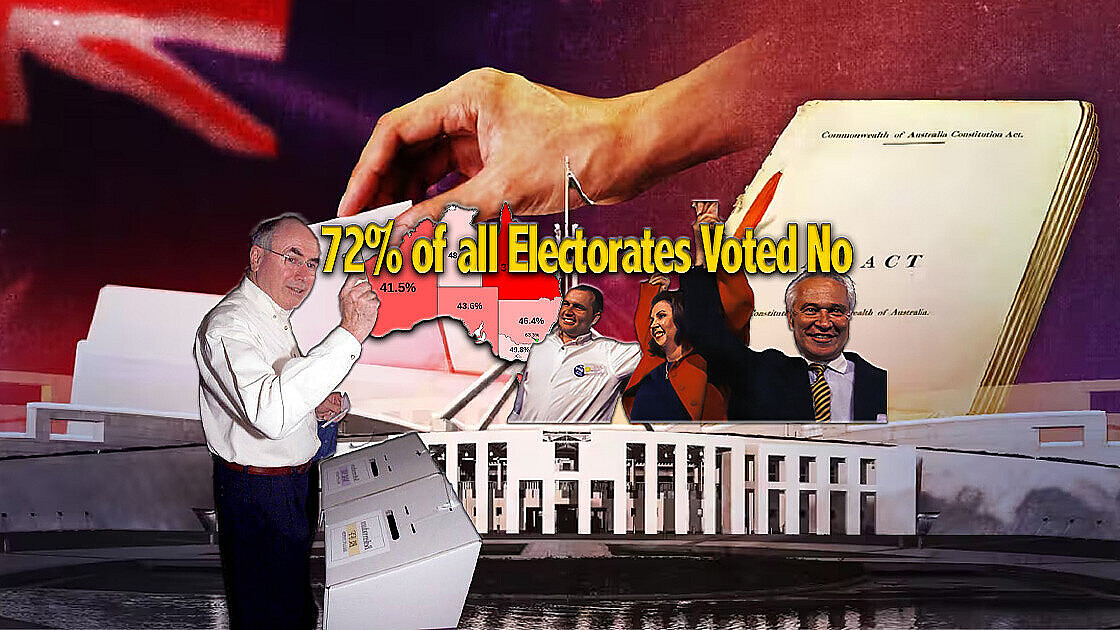

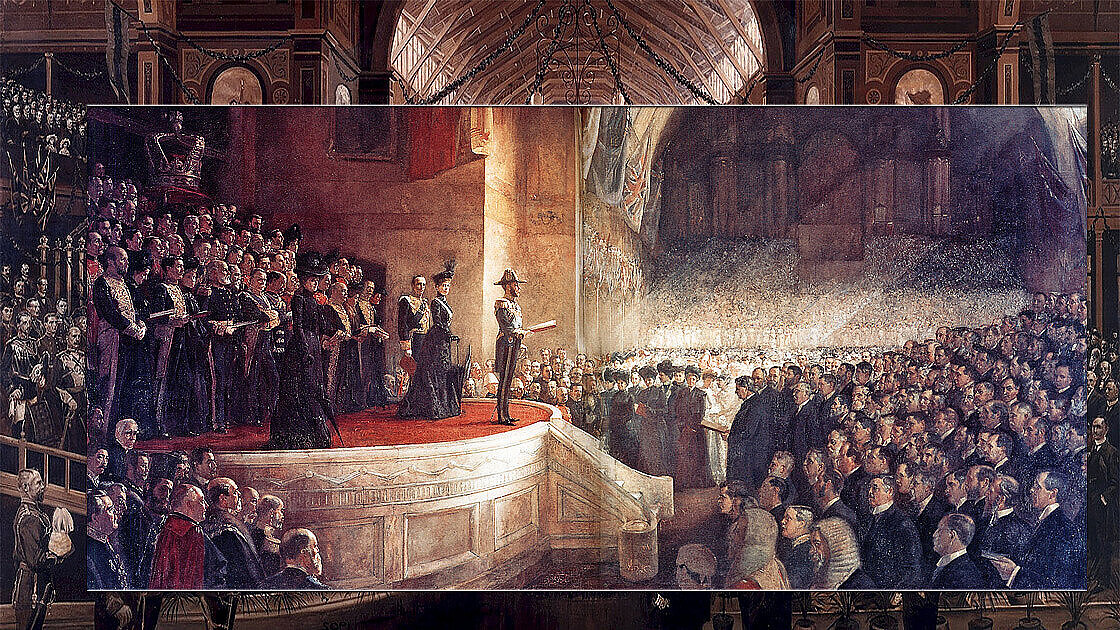

At the moment, our principal concern is directed to the conventions governing the relations between the governments of what were formerly referred to as dominions, now realms, and that of the United Kingdom and those governing the role of the governor-general. The federal constitution is concerned primarily with the division and separation of powers within Australia. It is not expressly concerned with resolving questions of nationhood or independence. A survey of Australian constitutional history reveals that Australia acquired independence by a gradual process – although the late Justice Lionel Murphy held that because Australians could change our constitution, we became independent in 1901.

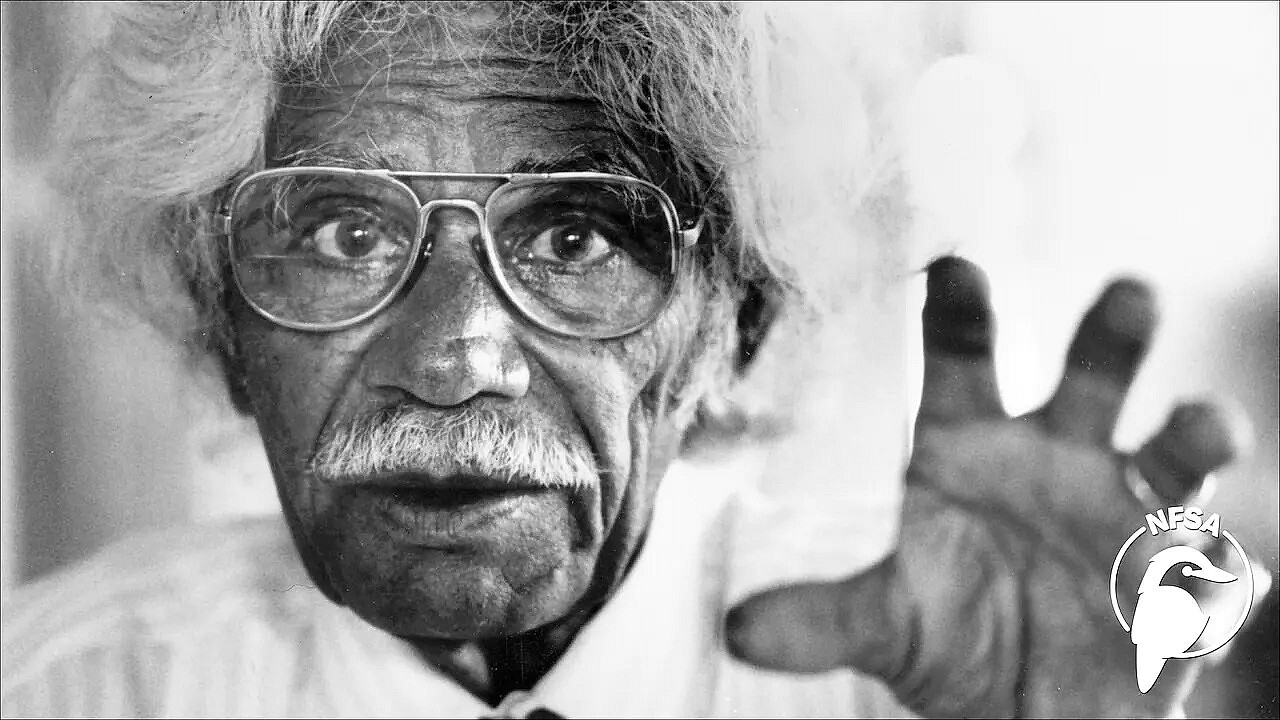

A gauge by which independence may be measured is the willingness of foreign national governments to enter into treaties with Australia. Justice Barry O'Keefe reminds us that after the First World War, Australia was represented independently at the peace negotiations by Prime Minister Billy Hughes. He presses the argument that Australia was a self-governing country, not subordinate to the parliament at Westminster, but rather a partner with equality of status, not necessarily (at that time) equality of stature. That argument was accepted as a hard practical fact by the nations, including Britain, that took part in the peace negotiations. Independence was well established in the international scene by 1920.

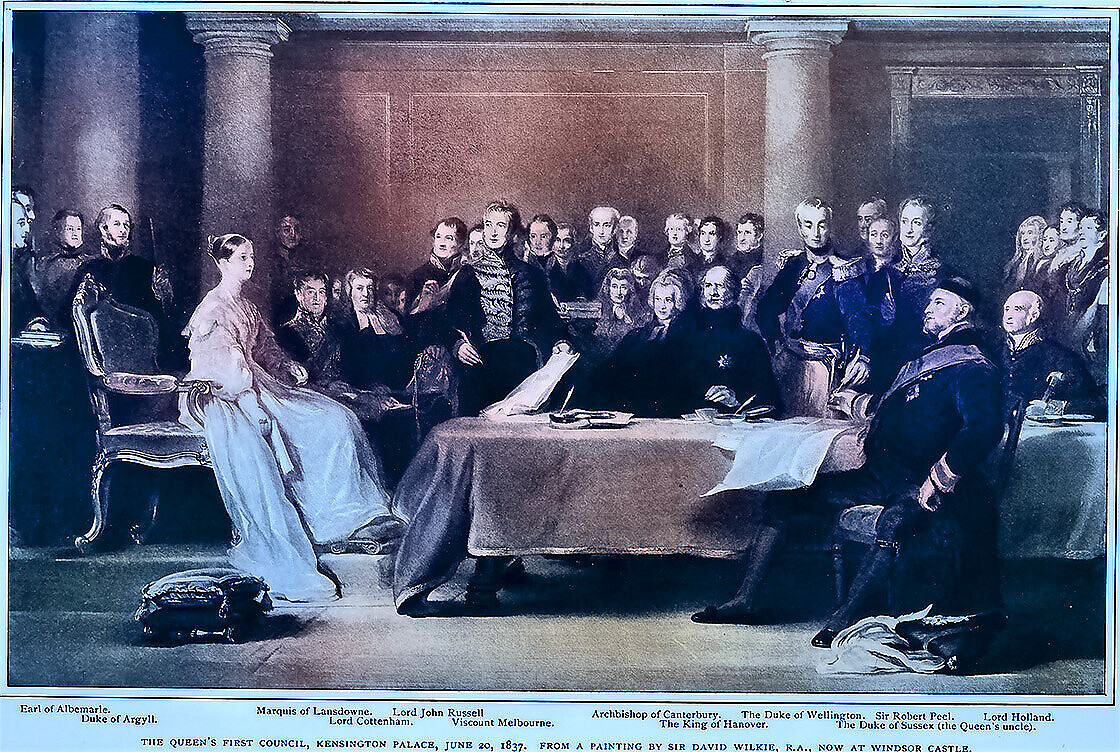

Australian independence came to be recognised at the Imperial Conferences of Dominion, and British prime ministers convened in 1917, 1926 and 1930. According to the Balfour Declaration, the dominions were autonomous communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the crown and freely associated, as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations.

This result was explained at the 1992 conference in these words:

The rapid evolution of overseas dominions during the last fifty years has involved many complicated adjustments of old political machinery to changing conditions. The tendency towards equality of status was both right and inevitable. Geographical and other conditions made this impossible of attainment by way of federation. The only alternative was by the way of autonomy, and along this road, it has been steadily sought. Every self-governing member of the Empire is now the master of its destiny. In fact, if not always in form, it is subject to no compulsion whatever.

The Balfour Declaration recognised conventions that had already been developed. The Declaration was given statutory effect when the parliament at Westminster passed the Statute of Westminster, 1931, which recognised the full emancipation of the dominion parliaments. Now they could enact laws repugnant to the law of England (section 2), and give "extraterritorial" effect to any legislation (section 3). The statute limits the competence of the United Kingdom to legislate for the dominions to circumstances in which the relevant parliament requested and consented to such imperial legislation (section 4). The act stipulated that the operation of the dominion constitution was not affected in any way (section 7 and section 8). It also stipulated that, unlike the Canadian provinces to which it would apply, the act would not apply to the Australian states. This was at their request (section 9). Finally, the act would not have any effect in Australia until the parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia adopted the act itself by means of an adopting act (s10). In fact, the commonwealth parliament did not adopt the statute until 1942, at which time the act was given a retrospective operation "as from the commencement of the war between His Majesty the King and Germany".

The precise point at which independence was attained remains a moot point. Was it the political compact? Was it the formal offer by the mother parliament? Or was it the formal acceptance of the offer by the newly independent dominion parliament? In a fairly recent judgement, Lord Denning MR maintains independence came as a matter of evolving usage and convention rather than by means of enactment:

Hitherto I have said that in constitutional law, the crown was single and indivisible. But that law was changed in the first half of this century, not by statute, but by constitutional usage and practice. (R vs Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs ex parte Indian Association of Alberta, 1982, 2 WLR, 641, at 651)

The passage highlights the role conventions have played in the evolving relationship between governments within the British Empire and the subsequent Commonwealth of Nations. Were such relations governed by the rigidity of statute such developments could not occur so naturally as need requires. The gradual emergence of full Australian nationhood was possible precisely because of the flexibility that is offered by convention. It has been argued that legal independence did not occur until the passage of the Statute of Westminster through both imperial and dominion parliaments was complete. In a passage dealing with the difficulty of making such a determination, Chief Justice Sir Garfield Barwick said:

The historical movement of Australia to the status of a fully independent nation has been both gradual and, to a degree, imperceptible ... though the precise day of the acquisition of national independence may not be identifiable, it certainly was not the date of the inauguration of the Commonwealth in 1901. The historical, political and legal reality is that from 1901 until some period of time subsequent to the passage and adoption of the Statute of Westminster, the Commonwealth was no more than a self-governing colony though latterly having dominion status. (China Ocean Shipping Co. v South Australia, 1979, 145, CLR 172 at 183)

The position was certainly resolved by the Australia Acts of 1986, which make certain that Australia is absolutely independent of the United Kingdom. Sir Anthony Mason, then Chief Justice of Australia, held this to be the true date of a hand-over of sovereignty, explaining that the Australia Acts: "marked the end of the legal sovereignty of the imperial parliament and recognised that ultimate sovereignty resided in the Australian people". (Australian Capital Television Ltd v Commonwealth, 1992, 177, CLR 106 at 138)

With the Balfour Declaration and the Statute of Westminster had come the termination of British legislative and executive responsibility, at least for the commonwealth, if not the states. Judicial responsibility remained, however, until the termination of appeals to the privy council (Her Majesty in Council), which had become part of the Australian court structure.

There are four significant points about the Australia Acts of 1986. Firstly, the bulk of the acts is concerned with severing those remaining legal ties between the states and the United Kingdom. These gave the state legislatures the full powers that the United Kingdom had previously retained — at Australia's request — to leg¬islate for the state as well as the power to legislate extra-territorially. The Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865 and the doctrine prohibiting repugnance to the law of England no longer applied (section 6). British executive responsibility and privy council appeals from the state disappeared (section 10 and section 11).

Secondly, the Acts clarify the role of the queen and the governors regarding the states. The state premiers would give advice on the exercise of royal powers, not through the British government, but direct to the queen. The premiers were never prepared to go through Canberra.

Thirdly, the Statute of Westminster was amended in several respects. These included the termination of the power of the United Kingdom parliament to legislate for the commonwealth, the states and territories thereof, even at the request of the Australian parliaments. (Notwithstanding this, over recent years, some Republicans have made the bizarre suggestion that the British parliament should be requested to impose a republic!) Now no British Act can henceforth apply to any Australian jurisdiction (section 11 and section 12).

Fourth, the Acts stipulate that the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act and the Statute of Westminster continue to be in force and provide an intricate method by which the Australia Acts and the Statute of Westminster may be amended. Both Acts, enacted in substantially identical terms by the United Kingdom and Australian parliaments, were proclaimed by the queen to come into effect on March 3 1986. On arrival in Australia to proclaim the Australian version, she observed both the rise of an Australian national identity and the circumstances under which the constitutional relationship between Australia and the United Kingdom had come to an end:

I can see a growing sense of identity and a fierce pride in being Australian. So it is right that the Australia Acts has finally severed the last of the Constitutional links between Australia and Britain, and I was glad to play a dual role in this. My last official action as Queen of the United Kingdom before leaving London last month was to give my assent to the Australia Acts from the Westminster Parliament. My first official action on arriving in Australia yesterday was to proclaim an identical Act, but from the Australia Parliament – which I did as Queen of Australia. Surely no two independent countries could bring to an end their constitutional relationship in a more civilised way, and I hope you will agree with me that this has been symbolic of the depth and quality of the relationship between Australia and Britain. Anachronistic constitutional arrangements have disappeared – but the friendship between the two nations has been strengthened and will endure. (McDonald, 67)

What we have seen since the adoption of the Australian con¬stitution is the gradual emergence of Australia as an independent nation. This surely is one of the beauties of our system – that it has permitted such a peaceful evolution.

As Sir Harry Gibbs explains:

Our Constitution has been criticised because it sketches the outline of the system of government and does not set out in detail the rules and conventions that determine the working of the various arms of government. Any such criticism is totally misconceived. The strength of our Constitution, as it has been the strength of the Constitution of the United Kingdom, is that it allows the needs of a changing society to be met by a gradual development, which has been found impossible in some nations whose written Constitutions attempt to lay down all the rules in detail. (Gibbs, 1994)

[Read More: Australia In The Twenty-First Century: An Independent and Self-Determining Nation, by The Honourable Barry O'Keefe, AM, QC ]